Friday, October 26, 2012

Saturday, October 13, 2012

Rihla (Journey 32): ROME, ITALY: HOMAGE TO ROBERT DOISNEAU

Rihla (The Journey) – was the short title of a

14th Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar Ibn

Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue

of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels

of Travelling and somehow the title of Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos

of many of the city and country journeys I have been lucky to take in past

years.

This rihla is about Rome and its people.

In Rome recently for a conference I was heading early one morning to the

Piazza d.Republicca Metro station along the Via Nazionale.

Outside the Palazzo Delle Exposizioni there were large posters advertising a

retrospective exhibition for the French photographer Robert Doisneau; famous for

his scenes of every-day life in Paris and particularly for his now infamous Le

baiser de l’hotel de Ville (The Kiss) which resulted in two law suits over its

‘staging’ and the identities of the couple involved. I thought about Doisneau’s

work as I headed towards the soulless conference centre at Fiera de Roma near

the airport and promised myself some time to try and capture some Roman scenes

the following afternoon. These are the result and if by chance any of the

people captured recognise themselves (particularly the young couple kissing)

please get in touch.

Tuesday, October 02, 2012

Rihla (Journey 31): CHALDIRAN, NW IRAN: SUNNI and SHIA ISLAM – THE BATTLE for FAITH and POWER.

Rihla (The Journey) – was the short title of a 14th Century (1355 CE)

book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar Ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada

who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian, Ibn

Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift

to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling

and somehow the title of Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos of many of the

city and country journeys I have been lucky to take in past years.

This rihla

is about Chaldiran in NW Iran.

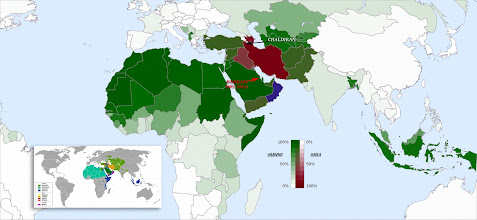

DISTRIBUTION OF SUNNI AND SHIA BRANCHES OF ISLAM

'Bahrain’s highest court has upheld jail terms

issued against nine medics – including Irish-trained orthopaedic surgeon Ali

al-Ekry – convicted for their role in last year’s pro-democracy uprising, state

news agency BNA reported. The controversial case has drawn international

criticism of the US-allied Gulf Arab kingdom, which has been in turmoil since

the protests led by its Shia Muslim majority were crushed by the Sunni rulers. Bahrain,

home base for the US navy’s fifth fleet, accuses regional Shia power Iran of

encouraging the unrest and has promised a tough response to violent protests as

talks with the opposition have stalled.'

Irish Times 2nd

October 2012

Throughout the Middle East and North Africa over the

past two years the so-called Arab Spring has seen in a parallel development to secular

demands for greater democracy an opportunist and orchestrated acceleration of

fundamentalist Sunni neo-militarism, funded in the main by Saudi Arabian based organisations, to fill the political and religious vacuums created by regime

implosions. To a great extent this Sunni militarism has focused on internal

control of faith and power (with occasional diversionary mob incitement against

western interests for such things as the publication of cartoons deemed

offensive) but where there is an obvious Shia opposition or power base such as

in Syria with the ruling Alawis, against the Houthis in Yemen, or as outlined

above in Bahrain then the Sunni efforts to eradicate Shia influence have become

most determined. This on-going schism amongst Muslims has led to atrocities

being perpetrated by both sides in a complete denial of what true Islam

purports to be.

And when blame is being apportioned where else does

Sunni wrath turn, to create a demonised target (and in the cynical way of

real-politic incite or be duped by the involvement of Israel and the

American-Israeli caucus) but to the dominant Shia entity that is the Islamic

Republic of Iran.

VALLEY OF CHALDIRAN LOOKING NORTHWEST

In nearly 1400 years from the time of the first

Islamic civil war (First Fitna 656-661 C.E.) the Sunni-Shia internecine

struggle for the control of power and faith in Islam (between Arabia and Iran)

has not changed much but one of its most violent expressions occurred at the

Battle of Chaldiran, in present day North Western Iran on 23 August 1514 when

approximately 7000 (2000 Ottoman Sunni and 5000 Safavid Shia) died defending

their version of faith in addition to a pre-emptive genocide of about 40,000

Anatolian Shia by the Sunni Ottomans in advance of the battle.

I like travelling in places where there are land

borders between states. In some instances the geography of that separation can

be as great as a high mountain range or as puny as a trickling stream. Frontier

people are different: equally accommodating or equally suspicious in two or

three languages, two political rhetoric’s, two legislative structures, two

religions, or two or more versions of the truth and very often as a family, a

clan or a tribe will straddle the divide. At frontiers your senses become

alive, alert to nuances that elsewhere become mundane.

ISHAK PASHA PALACE DOGUBAYAZIT, TURKEY LOOKING NORTH

In October 2008 while travelling in Eastern Turkey I made my way to

Dogubayazit, a large city about 35km from the Turkish-Iranian border. It sits

in a green valley in the lee of snow-capped Mount Ararat (known by the Arabs as Jabal al-ārith, by the

Turks as Büyük Aǧrı Daǧ, by the Iranians as Kūh-i Nū_ (Mountain of Noah) and

as Mount Masis, or Masik, by the Armenians) and spent the

morning dodging Turkish soldiers and Kurdish vendors on very dusty streets. Later on a balmy afternoon I sat

on the terrace of the small restaurant that overlooks the magnificent palace

fortress of Ishak Pasha, which is built on a high valley buff that stands

sentinel over Dogubayazit from the south. To the east and against the valley

wall were the ruined walls of an Urartu fortress and a small mosque. A man

beside me watched me take photographs and then he introduced himself. He was a

Kurd, from Diyarbakir, a lawyer educated in Paris and London, in Dogubayazit

representing some local men who had been rounded up in a recent Turkish

crackdown on Kurdish secessionism. He pointed to the small mosque and told me

it had been commissioned by the Ottoman Sultan, Selim I, known as The Grim, on

his way to a place called Chaldiran, which lay about 70km to the south-east in

Iran. The Battle of Chaldiran, he told

me was not only a dogma defeat for the Shia Iranians by the Sunni Ottomans but

also was responsible for splitting the Kurdish homelands into two halves of

influence, a situation which has existed to this day.

Selim I, Yavuz Sultan Selim Khan (Yavuz means steadfast but was often

translated in English as the Grim) came to the Ottoman throne in 1512 CE.

Having battled and then forced the abdication of his father Bayazit II he

subsequently defeated and then killed his rivals for the throne, his brother Ahmet

in April 1513 as well as his other brother Korkut and nephews, thereby

eradicating all internal opposition. He then turned his attentions to the east

where the opposition was of a greater danger to his authority, his sultanship.

Shah Ismail I, founder of the Safavid dynasty, was

the last of the hereditary masters of the Safaviyya Sufi order. His father had

mobilized Turkomen tribes into militant Qizilbash ( ‘Red Heads’ so-called from

the red peaks to their turbans and the 12 perforations denoting the 12 Imams of

Twelver Shiism) groups. In 1501 Ismail with the support of the Qizilbash troops

was crowned Shah of Azerbaijan and by 1510 Shah of Iran. On accession to power

he declared Shi’sm to be the State Religion and began dispatching Qizilbash

missionaries deep into the heart of Ottoman Anatolia (where in 1511 they

orchestrated a revolt against Bayazit II that eventually signalled his

downfall). In addition he advanced his forces as far as present day Diyarbakir

and southern Iraq. His ascension, and the ascension of a Shia state posed a

direct threat to Ottoman religious and temporal authority.

Selim I, in response, gathered an army of 140,00 and

force-marched it from Sivas in central turkey to Dogubayazit and then upwards

to the high valley of Chaldiran where an army of about 40,000 Qizilbash troops

under Ismail I had gathered. In 1511 following the suppression of the Qizilbash

Turkomen-Alevi Kurd Shia Shakulu uprising 40,000 Shia were exterminated and to

ensure that no further Shia remained behind his army to cause trouble Selim had

ordered Yunus Pasha, before setting out on campaign, to supervise the inquisition

and massacre of all Shia in his dominions. This distrust of Alevism still

exists in Turkey today.

‘Then, with the support and

assistance of God, I will crown the head of every gallows tree with the head of

a crown-wearing Sufi and clear that faction from the face of the earth .... and

maneuvering in accordance with “Put them to death wherever you find them” (Qur’an

4: 89), will wreak ruin upon you and drive you from that land.’

Selim I

In advance of the armies meeting Selim and Ismail had

exchanged diplomatic correspondence. Ismail dictated his in Azerbaijani Turkish,

which was the language of his people and of his powerbase. Selim on the other hand

replied in Persian, which he knew Ismail did not have a full grasp of. They

insulted each other by referring to each other’s addictions. In Ismail’s case

it was his liking for alcohol and in Selim’s case for opium. Indeed in the

final communication before the battle Ismail sent an ambassador, Shah Quli Aga

with a golden casket full of opium for Selim with the request that no harm come

to the ambassador.

‘Bitter experience has taught

that in this world of trial

He who falls upon the house of ‘Ali always falls.

Kindly give our ambassador leave to travel unmolested for “No soul shall bear

another’s burden.” (Qur’an 6: 164; 53: 38) When war becomes inevitable,

hesitation and delay must be set aside, and one must think on that which is to

come. Farewell.’

Ismail I

Selim had Quli Aga executed for the insult on the

spot!

THE BATTLE OF CHALDIRAN 23 AUG 1514

TROOP DEPLOYMENTS

Around the 23 August 1514CE Sultan Selim’s troops

entered into the valley of Chaldiran from the north. Knowing that they were

heavily outnumbered some of Ismail’s commanders requested that they attack

immediately before the Ottoman army had a chance to fully deploy. In the centre

of the Ottoman forces were cannon batteries and a battalion of crack Janissary

troops. Ismail refused, believing in his own sense of invincibility and also an

archaic code of chivalry. Ismail’s forces did not have cannon ( a mistake they

never made again) and on the morning of the 23 August 1514 his cavalry began to

attack the Ottoman flanks. The ottoman artillery decimated them and the Safavid

army was driven from the valley with 7-10,000 dead and leaving behind one if

not two of Ismail’s wives who were subsequently married off to Ottoman

generals.

There are two other interesting asides to the battle.

Firstly Selim entered Tabriz, the Safavid capital,

and wanted to pursue the retreating Ismail towards the Caspian but was

dissuaded by his Janissary commanders who partially revolted, explaining that

because of Ismail’s scorched earth policy in eastern Anatolia the army could

not be kept supplied. Although the Janissary troops loved their food it is

possible that the hesitation on their parts was that the Janissaries were

closely allied to the Becktasi Sufi Order a very similar order to that of

Ismail’s Safaviyya and may not wanted to pursue their co-Sufi.

Secondly in a positive development Ismail’s empire

was noted for its Timurid inspired artists and calligraphers and upwards of

1000 artisans from the Safavid dominions were transported back to Istanbul

where they provided the fundamental spark to the subsequent flowering of the

high period of Ottoman art.

On St Patrick’s Day, the 17th March 2009,

I travelled up from Tabriz in NW Iran to see the battlefield and valley of

Chaldiran for myself. Approaching from the south-east having first stopped at St

Thaddeus Monastery and Qara Church the sense of theatre could not be dismissed.

A bitter-cold wind whipped in from the east. Snow-capped mountains rising to

2600m surrounded a fertile plain which is at 1820m above sea level with a

single natural exit point to the north and to the south. There is a battlefield

memorial between the villages of Sa’dal and Gal Ashaqi on the western rim of

the valley.

Chaldiran is a Coliseum on a grand scale, a killing

zone where Sunni and Shia exterminated each other in the name of faith and

power and left a legacy that resonates to this day.

The silent screams deafened, as they now do in

Aleppo, Syria and Manama, Bahrain.

Friday, September 07, 2012

Rihla (Journey 30): Marlfield, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary: COCKAYGNE, NOSTALGIA AND THE TREE OF LIFE.

Rihla (The Journey) – was the short title of a 14th Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar Ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling and somehow the title of Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos of many of the city and country journeys I have been lucky to take in past years.

This rihla is about MARLFIELD, CLONMEL, CO. TIPPERARY and NOSTALGIA

The Land of Cockaygne c1330CE

An abbey’s there, a handsome sight,

Of monks with habits grey and white.

The house has many rooms and halls;

Pies and pasties form the walls,

Made with rich fillings, fish and meat,

The tastiest a man could eat.

The Land of Cockaygne

A 14th Century Irish Satire

After travelling to southern Turkey earlier this year to see Gobekli Tepe my night dreams began, inexplicably, to incorporate images of my grandson Leon and of a large tree; a tree I immediately recognised from part of own childhood in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary. On the flight home I fell into conversation with the passenger next to me. By chance he was a laconic Waterford man, a true Spartan from the Nire Valley, returning via Istanbul from Azerbajan where he had found work with a construction firm following the implosion of building sector here in Ireland. We began discussing the whole notion of imprinted memories and nostalgia, and I told him of the recent dreams and of a real desire to revisit the tree if it still existed.

He smiled as he looked at me, and observed, “Roger. There is no future in nostalgia… or in Clonmel at the moment.”

And of course this is true. Nostalgia does not have an antonym or word opposite in the English language. There can be no emotion of future longing, a desire to re-experience something that has not yet happened. You can muse upon the present, or anticipate the future in an abstract way, but deprived of memory, of an imprint they are lesser emotions. Umberto Eco might say that nostalgia is a place to store emotions that would clutter the present and obviate the future and for many (perhaps necessarily) it can become either an indulgence or an escape.

Marfield, when I was growing up there between 1960 and 1968, was a small village on the west side of Clonmel on the road from Ardfinan. Today the village and the remainder of the parish of Inislounaght (leamh neachta – Isle of the Fresh Milk) are part of the expanded town. Marlfield was the site of a 7th century early monastic settlement on which Malachy O’Phelan, lord of the Decies and Donald Mor O’Brien, King of Munster encouraged the Cistercians of Mellifont Abbey to the south, to establish a daughter-house.

The Abbey of Inislounaght known as de Surio was founded in 1148 and always seemed to attract trouble, both from within and without. It was the subject of a satire poem, the Land of Cockaygne, written by rival Franciscans in 1330 documenting the Cistercian delight in the good life at the Abbey and subsequently fell on hard times. In 1537 the Abbot James Butler was accused of being a man of ‘odius life’ who ‘taking yearly and daily men's wives and burgess' daughters keepeth no divine service but spends the goods of his church in voluptuosity, and mortgages the lands of his church and so the house is all decayed’.

In 1540 the Abbey lands were surrendered to Thomas Butler, a local farmer and the first Baron Caher, although the last titular Abbot was a Laurence FitzHarris who fled the Crowellian forces to France in 1649.

As you drive in from Ardfinan you are in the land of big houses and former big estates. Leaving Knocklofty House behind, once the home of the Earls of Donoughmore, you soon enter the village and then at the crossroads to Patricks Well and Marlfield Lake you turn right down the lane to Marlfield House, former home of the Bagwell family, and the sandy bank on the River Suir where we learnt to swim. Near the end of the road you meet on the left the entrance to St Patrick’s Church of Ireland, which stands on part of the site of where the Abbey once stood.

St Patricks COI, Marlfield, Clonmel.

Sweet Chestnut, Avenue.

The church is an evocative place, with overgrown graves and a sentinel parade of sweet chestnut trees where every autumn as children we gathered ammunition for the ‘conker’ fights in school. The ‘Abbey Nuts’ were the very best and the effort to sneak past the house where the local ‘bogey man’ lived to get them was always worth it.

St Patricks COI, Marlfield, Co. Tipperary.

East End Gable.

As I walked down the avenue, nostalgia had nearly completely taken over. The childhood swims in the river, the conker trees, the place where Theo English made his famous hurleys, the house where we bought fresh eggs, the house where Susan McGrath my first great passion lived. I wonder at what age does nostalgia take root? When do memories become a beacon of longing? And of course when did the ‘tree’, the tree of my childhood life take such a hold.

Leaving the village towards Clonmel I crested the hill and slowed as the house entrance approached: Birdhill. The old house, burnt down in the 1920 reprisals that destroyed many of the old landlord homes throughout the country, was bought by my father in a poor state of repair in 1960 and when we left it in 1968 it was only partially restored. A winding avenue through the fields where my brothers and I chased each other on bareback ponies with bows and arrows (there were no cowboys only Indians) brought us to the house. Somebody had spent an enormous amount of money in reviving its former glory and I was gobsmacked by its beauty.

So beautiful it undermined somewhat my memories of dilapidation, of freedom, of chaos and of happiness. I parked the car and knocked at the door. There was nobody at home and disappointment enveloped me.

But then I turned to look at the tree.

The tree, a specimen Monterey Cypress, rose majestically to the sky, its canopy topping out at about 100-120 ft. This tree was the rite of passage of my childhood, as each year of maturing bravado drove me higher and higher up the trunk until I crested it about the age of 10 or 11. At a recent funeral for my uncle a cousin of mine mentioned that his family had, on an early Super 8 film (first released 1965), footage of me waving down from the top of the tree.

Beyond the tree was a fruit garden and this is where the medlars grew. This is a nostalgic taste, and by way of further documentary evidence I have in my possession still, from my time in Clonmel Mrs Bagwell of Marlfield House’s handwritten and typed personal recipe book. Amongst hints for making cheap household soap, destroying rats and Sheep Head’s Pie there is a recipe for Medlar Jelly.

I don't think I can remember the taste of medlar jelly of my childhood and thus, that is the next journey.

And also to try and remember what Susan McGrath really looked like!

All travel, on the road, in the mind, is a quest for the emotional warmth that only nostalgia can evoke.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)