Wednesday, December 07, 2016

Thursday, November 10, 2016

RIHLA (Journey 72): GALWAY HARBOUR – THE DEEP BLUE SEA: AN EARLY 20th CENTURY LOCATION FOR A TRANSATLANTIC DEEPWATER PORT

Looking South West over Aillebaun Headland from Blakes (Gentian) Hill

Rihla (The Journey) – was the short title of a 14th Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar Ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling and somehow the title of Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos of many of the city and country journeys I have been lucky to take in past years.

This Rihla is about dreams, and delusions and the deep blue sea.

DAYDREAMS AND WET SOCKS.

Returning home with the dogs across the sandy beach that runs off the Aillebaun

headland I found myself having to quicken my pace before the incoming sea prevented

me from crossing the river that cascades through the barna gap of Rusheen Bay, a river which can disappear very quickly

beneath a flooding tide. Despite my hurrying I still had to, once across the

river, remove my Wellington boots to empty out the water of a miscalculated

transit and sit on a rock to wring out my socks. From my sodden vantage point

the grey-blue waters of Galway Bay were still, as they had been for the previous

week, untroubled by Atlantic swell or squall and in the distance, to the

south-west, the purple shadows of the Aran Islands lay at anchor on the

horizon, gently lapping against the sky.

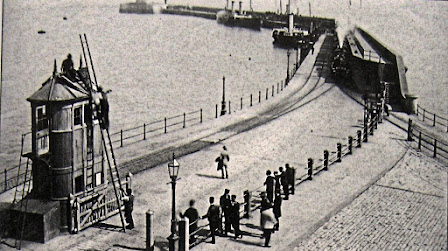

Imaginary Train coming in from proposed East Pier of

1911 Barna Deep-Water Transatlantic Port

As I day-dreamed on the notion of anchorage I realised that given a

different history, a different outcome of dreams, that instead of being perched

on a glacial discard, I could have been sitting on the hewn quayside of Barna’s

deep-water Transatlantic Port watching the bustle and groans of a busy modern

harbour winding down for the day. To my left a train would have been making its

way behind me with containers from the cargo terminal on Pier 1 while to my

right its companion engine would have been entering the tunnel beneath

Aillebaun brining tourists from the ocean liner docked at Pier 2 back from

their day in the city, in time for dinner.

Rusheen Bay

A chilling of the air brought me back to reality and the imaginary trains

suddenly derailed. The sun was setting fast and at this time of year the sunset

is sometimes sudden, brutal almost, the sky mutating from a brilliant amber to a

dirty grey in an instant: a rapid shift from daydreams to the stuff of nights. Beyond

Inis Meáin and the other Aran Islands on the horizon, are the depths of the

ocean, and in the chill of twilight I know that yet another storm will soon form,

and once again the waters and sky of Galway Bay will churn with its ferocity

and darkness.

As early as the 9th century Latin chroniclers and Arab

geographers began referring to the Atlantic Ocean beyond the Straits of

Gibraltar as the Mare Tenebrosum or Bahr al-Zulamat, both meaning “The Sea

of Darkness”. 1 As the Arab geographers would have it, where the

Atlantic was concerned, the “depth of darkness” below the ocean waves was

matched by the “depth of darkness” above those waves in the shape of billowing,

foreboding, storm-laden clouds coming rapidly over the horizon.

Whether it was 900 CE or 1900CE the Atlantic always seemed to have

associated with it a sense of adventure, but more often as not an equal

ignorance of its dangers…. and its vortex of shattered dreams.

DAYDREAMS AND GALWAY PORTS

In 1830 the Galway Docks and Canal Bill was passed with two aims in mind:

to establish and maintain a navigable canal between Lough Corrib and the sea,

and to improve and develop Galway Harbour to “facilitate and augment the Trade

of the Town and Neighbourhood.” The entire project was meant to have been the

responsibility of the Galway Harbour Commissioners but problems with managing both

the contract and the finance of the key inner harbour wet dock, caused a dispute

between the Harbour Commissioners and the Board of Works. The dock was not

completed until 1843 by which time the Board of Works had appointed a receiver

to collect the tolls instead of the Harbour Commissioners.

These problems with completing the inner dock also held up progressing

the canal element envisaged in the 1830 Bill. Work eventually began in 1848 on

the canal, which was ¾ mile long and whose construction included dredging the

Corrib, building a second wet dock at the Claddagh, five swivel bridges, two

quays and one very large lock. Managed entirely by the Board of Works, by that

time primarily as a famine relief scheme, the Eglinton Canal and its associated works were completed and

opened without much in the way of any fanfare in August 1852. 2

Claddagh Basin 1870

Terminus of Eglinton Canal

As early as 1830, Galway was identified as a possible location by the

Admiralty as a site for the main Packet Station connecting the British Isles

and North America, but any moves in this direction would not be possible unless

first, Galway was connected by rail to Holyhead on the East Coast and secondly,

development of the outer harbour as a safe refuge for ships took place. Despite

the completion of the Midland Great Western Railway into Galway,3

five months ahead of schedule by the contractor William Dargan on the 20th July

1851, progress on developing an outer harbour, suitable for handling the

transatlantic steamships, was constantly mired in vested-interest local,

national and British Isles politics, as thick as that of the mud that first had

to be dredged and as solid as the ship-breaking rocky bar or ledge right in

front of the new inner wet-dock gates which the contractor had failed to

remove.

Any development in these years had to be seen in the light of the

devastating effects of the Great Famine, caused by potato blight, between 1845

and 1852. In 1848 there were food riots in Galway. Between 1847 & 1848

11,000 people died in the city’s workhouse. In 1841 the population of Connaught

was approximately 1,418,859 but by 1851 it has been estimated that 239,529

(16.9%) men, women and children had died and 245,624 (17.3%) had emigrated. 4

As a consequence of the Famine the emigrant trade became a significant

part of Galway’s daily life and commerce. In 1851 alone 18,000 people from the

town and county left and between 1846-51, on just one of the emigrant routes

from Galway, 69 ships left for New York alone. A renewed effort was therefore

made to position Galway as a Transatlantic Port in the early 1850s. Much of

this effort pivoted on the personality and bravado of a Rev Peter Daly, who in

addition to being a parish priest was also one time Chairman of the Town

Commissioners, Chairman of the Harbour Commissioners, a board member of the

Midland Great Western Railway (MGWR)company and founder of the Royal Atlantic

Steam Navigation Company (The Galway Line) with J.O. Lever in 1858. 5

As part of his mercantile association with the Galway Line he proposed building

a new, and very elaborate, deep water Transatlantic Port off Furbo.

In 1852 the Rev Daly, as Chairman of the Galway Harbour Commissioners,

had also made submissions on behalf of the Harbour Commissioners to the

Admiralty Committee inquiring into the Suitability of Ports of Galway and

Shannon as Transatlantic Packet Station. This enquiry re-ignited the centuries

old – and still persisting if recent pronouncements on the building of a liner

port in either Foynes or Galway is noted – rivalry and mercantile jealousy

between Limerick and Galway when as early as 1377, the magistrates of Galway

were ordered not to extract customs duties from Limerick merchants, an

arrangement which was not operative in the reverse.6 The three Naval

officers commissioned to write a report for the committee felt that neither

Galway or the proposed ports on the Shannon estuary, with their current infrastructure,

were suitable as transatlantic ports but in November 1852 the Admiralty recommended Galway to the Board of Trade as

the packet station for transatlantic communication.7

Admiralty Pier Dover Built c1850s

A further report on the development of Galway Harbour as a Refuge

Harbour, was commissioned by the Admiralty in 1859, and three separate designs

were submitted for consideration. 8 A new Harbour Bill to finally

propel the development of an outer harbour incorporating the Mutton Island

causeway was passed in the Commons in 1861 but the clause looking to impose a

levy on the County of Galway to help pay for the development was rejected by

the House of Lords, despite the pleas of the Marquis of Clanricarde ( a deBurgo

descendent). The Board of Trade had approved the Galway Pier Junction Railway

Bill authorising the MGMR to build a branch line from Lough Atalia over the

Corrib and then down through the Claddagh to the Mutton Island causeway at Fair

Hill.

Building a Pier

As had been the case to date nothing really happened! The Rev Peter Daly

despite his industry was losing friends fast, at a religious, political, media,

landlord and mercantile level. Around the same time that the new Harbour Bill

languished, the main shipping line servicing the port and requiring a suitable

outer harbour to be built was in trouble. The Galway Line which had been

subsidised by the Royal Mail to the tune of £3,000 per annum to carry mail to

Newfoundland, became as Tim Collins has put it, “a heroic failure” due to

shipping disasters and scheduling deficits. Under pressure from the Cunard and

Inman Lines who started calling at Cork, and the development of transatlantic

cables, the Royal Mail contract for the direct Galway-North America service was

withdrawn in May 1861. In addition to this the Rev Peter Daly died in 1868 and

much of the local energy driving the development of an outer harbour

dissipated, or foundered like the Galway Line’s ship the Indian Empire on the

Margaretta shoal.

Approaching Galway Inner Dock 1872

In 1885 there was a further effort made to get the Harbour at Mutton

Island built but this time using convict labour. It was estimated that it would

take 450 convicts 20-25 years to complete the project. 9 Again in

1895 there was yet another attempt made but the projected cost had risen from

£155,000 (€21,266,000 in 2016 values) in 1852 (when the cost of laying down a railway line was £4011 [€553,000] per mile) to £670,000 (€79,560,600 ) in

1895.

DAYDREAMS AND BARNA TRANSATLANTIC DEEP-WATER PORT

After a decent interval to allow Davy Jones fully claim the restless soul

of the Rev. Peter Daly, spurred on by a pamphlet written by Richard J. Kelly, the owner of the Tuam Herald newspaper, a new evangelist contractor appeared on the scene,

ready to promote and develop a transatlantic deep-water port: Robert Shaw

Worthington.

Worthington was a Dublin-based railway construction contractor who first

came to attention as the contractor on Sallins-Blessington and

Blessington-Tullow connection for the Great Southern & Western Railway

Company, which were completed in 1885 and 1886 respectively, at the same time

that he completed the huge Robert Street Malt Store for the Guinness company.

He then went on to build the Cork and Muskerry Light Railway on time and on

budget in 1887-1888, the Loughrea & Atymon Light Railway for the Midland

and Great Western Railway Company(MGWRC) in 1890, and the Ballinrobe & Clarmorris Light Railway, again for the MGWRC in 1892.

In early 1891 Worthington was also contracted by the MGWRC to do the

preliminary surface work over the extensive boglands for the proposed Galway –

Clifden railway line, but he ran into conflict with both his workers, whom he

underpaid and who went on strike, and the MGWRC engineers. His foreman at the

time attributed the problem to the local Connemara men not being used to using

the short but wide “Navvie” shovel! In any event Worthington was not offered

the contract to build the railway proper and retreated for time back to Dublin.

However the even worse performance of Charles Braddock, who was awarded the

contract instead, managed to portray Worthington in a more favourable light and

in 1893 was contracted by the MGWRC to build the Achill extension of the

Westport line. This was completed in 1895.

With the completed Achill, Clifden and Galway Extensions

of the Midland & Great Western Railway Tourism began in the

West of Ireland. Poster c.1900

Worthington by this stage had developed grandiose ambitions, in trying to

match William Dargan, the doyen of the Irish Railway construction engineers. He

had developed a number of close personal and influential friendships with the likes

of the Prime Minister of Newfoundland Sir Edward Patrick Morris and the

barrister-owner of the Tuam Herald Richard J. Kelly. Both Morris and Kelly

strongly supported the development of a deep-water harbour in Galway to serve

in particular the shortest sail-time “Red-Route” across the North Atlantic to

Newfoundland. Armed with this support

and with start-up funding for a necessary Parliamentary Bill from the Chairman

of the Midland and Great Western Railway to the tune of £5,000

(€658,000) Robert Worthington returned to Galway in 1909 with a very solid proposal to

build and service a Transatlantic Port at Barna. He was welcomed with open

arms.

Galway's Deep Harbour Plans in Library of NUIG

Worthington was astute. He knew that the first item on the agenda, if a

Parliamentary Bill was to be successful, was to identify and get onside the

owners of the land that might be required, as well as the local mercantile

community. He formed the Galway Transatlantic Port Committee in 1910 and induced

the Bishop of Galway, Lord Killanin, the aforementioned Richard J. Kelly, and

Marcus Lynch of Barna, who was chairman of the Galway Harbour Commissioners, to

become part of that committee. The Committee also included Dublin and Galway

town commissioners as well as a representative from the MGWRC and was chaired

by Lord Killanin. The Committee went about submitting a required Bill for Parliament’s

consideration as well as contacting relevant bodies such as the county councils

in Ireland and the Prime Ministers of New Zealand and Newfoundland to get their

specific support for the proposal.10

The Committee also engaged the services of Arthur D. Hurtzig of the distinguished

engineering firm Baker & Hurtzig, who had, as engineering consultants, just

completed the Aswan Dam across the Nile. Hurtzig visited Galway in May 1911,

was met by Marcus Lynch and Col Courtney and subsequently submitted a design

proposal. Unfortunately the proposal appears to have stopped there. Despite

their efforts Parliamentary support for the scheme was not forthcoming, and having

been left on “the Table” for consideration it languished there for 2-3 years before

being finally abandoned when the Midland and Great Western Railway withdrew

their support in early 1913. Worthington was livid, and in a letter to the

MGWRC Board in July 1913, pleaded for financial help in supporting the

Parliamentary process and not the construction. He stated that he had the

construction costs of €1,500,000 (€200,000,000), pending Parliament passing the

Bill, available. 11

Although there is little documentation to back this contention I also suspect

the direct support of Marcus Lynch of Barna to the project was essential. In

1870 the Lynches of Barna owned 4,100 acres of land in Galway and by 1905 still

controlled most of the land where the servicing and building works area for the

projected port and west pier were to be located. Had the proposed port

proceeded it would have proved to have been an interesting set of negotiations to

free up the part of Lynch’s land required for the development.

In 1906 Marcus Lynch had leased the land to the east of Barna Woods to

Galway Golf Club – of which Lord Killanin was President and Colonel Courtney,

Captain – to establish their second home. The need for this arose when Sebastian

Nolan had evicted the Club from the original course that Nolan and Lt. Col

H.F.N. Jourdain of the Connaught Rangers had designed and built on Blake’s

(Gentian) Hill. 12 Nolan had bought the Blake’s Hill headland from

the Alliance Assurance Company of London in 1895 for about £680 (€99,176). The

Allied Assurance Company had been established in 1824 by Nathan Mayer

Rothschild, the English banking scion of the Rothschild family and had come to

control the mortgages on large amounts of land in Connaught.

The land required for the projected east pier of Barna Transatlantic Port

off Blake’s Hill would have required acquiring Sebastian Nolan’s former lands

from the Church. Nolan had died playing golf on the Hill in April 1907 and

probate of his estate of £40,469 12s (€5,405,400) was granted to the Most Rev

John Heally, the Archbishop of Tuam. No doubt the presence of the Bishop of

Galway on the Transatlantic Port Committee would have smoothed the “reasonable”

sale of the required lands. Worthington, and perhaps Marcus Lynch in the

background, seemed to have thought of every eventuality in their detailed

planning.

Despite his family’s history and previous wealth Lynch appeared to be in

serious economic straits by 1910 and would have welcomed the opportunity to

extract himself with the sale of his land to the proposed Transatlantic Port. However,

as with all other Galway Outer Harbour efforts over the previous 60 years the

Barna Transatlantic Port was not to be and by the time Lynch died in November

1916 the scheme had been completely shelved. Marcus Lynch left probate of his surprisingly

small estate of £2,048 16s 0d (€175,420) to his sister Margaret.

Robert Worthington was also left a good deal poorer by his involvement

but this did not deter him from marrying three times and fathering eight

children. He died in 1922 at the age of 80.

THE DREAM CONTINUES

Proposed Galway Port 2015

The 180 year-old dreams of a Transatlantic Port for Galway have not gone

away. 13 I have no doubt that any day soon Fr Peter Daly and Robert

Worthington in Rip Van-Winkle mode will arise and meet each other’s ghost! In

order to service the increasingly lucrative ocean liner tourism a plan has been

put in place by the Harbour Board and now all efforts are being made to get

national and European funding to get the project started. Interestingly as it

has been for nearly 700 years this aspiration has pitted mercantile Limerick

against Galway again, with Limerick vying for the same funds to develop an

ocean liner port at Foynes on the Shannon estuary.

Galway Inner Dock 2016

REFERENCES:

1.Lunde

P. Pillars of Hercules. 1992 Aramco World 43, 3

2.Woodman

K. ‘safe and commodious’ – The Annals of the Galway Harbour Commissioners

1830-1991, 2000, Galway Harbour Company

3.Hurley

MJ The Galway Train 2016 Lackagh Museum & Community Development

Association. Smashwords.com

4.Ó

Gráda C, O’Rourke KH Migration as disaster Relief: lessons from the Great Irish

Famine. 1997 European Review of Economic History, 1 (1): 3-25

5.Collins

T. Transatlantic Triumph and Heroic Failure: The Galway Line 2003 Collins

Press, Cork.

6.Hardiman

T. History of the Town and County of the Town of Galway. 1820 Folds & Sons,

Dublin, p.60

7.British

Parliamentary Papers HC1859 (257) Session I XVII

8.Report

to Admiralty by Capt. Washington R.N., Captain Vetch R.E. and Mr Barry Gibbons

C.E., on the Capabilities and Requirements of the Port and Harbour of Galway.

House of Commons. 2nd March 1859

9.Kelly

RJ. Galway as a Transatlantic Port. 1903 Pamphlet, McDougall & Brown,

Galway. p 24

10.Ocean

Mail Services, (Additional Papers), Houses of the General Assembly, Session II,

1912, New Zealand; Papers 256 & 257, p. 76

11.Worthington

RS, Galway as a Transatlantic Port, 1913 The Railway Times, p.80

12.Derham

RJ. Galway – Guano, Golf, and Gethsemane: June 26, 2015 Available at: http://deworde.blogspot.ie/2015/06/guano-golf-and-gethsemane-in-galway.html

13.http://www.galwayharbour.com/new_port/

Friday, October 28, 2016

RIHLA (Journey 61): GALWAY – A Medieval City State 1232 -1694

Rihla (The Journey) – was the

short title of a 14th Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic

legal scholar Ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed

the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title

was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the

Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling and somehow the title of

Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos of many of the city and country journeys I

have been lucky to take in past years.

Some of the best journeys you can take are those

closest to you.

INTRODUCTION

Ignoring any mythical or invented compound etymological

derivation, Galway is as it always has been: Gaillimh – the Place of the Foreigners, the Gaill – and a city from its earliest foundation dedicated to

trading and mercantile adventure.1

How do we know this?

The Gaelic territorial area or túath surrounding Galway is the túath

of the Clan Fergaile – the túath of

the “Men or Middlemen of the Foreigners” – and the dominant sept of the Clan

Fergail were the O’Hallorans, who in turn were a subject clan to the O’Flahertys

of Maigh Seola, and ultimately the O’Conor Kings of Connacht.2

O’Halloran is the English translation of O’h-Allmhurain,

the descendents of Allmurhan, which derives from the Gaelic allumhaire – “one who imports”.3

The O’Hallorans settled in the Galway area in the 6-7th

centuries and established Galway as a wic or emporium trading with Gaulish

traders from about that time. In the 1230s the Anglo-Norman family the deBurgos

invaded Connacht and dispossessing the O’Hallorans and the O’Flahertys

displaced them across the Corrib and Mask lakes to the wild-west territories of

Iar Connacht where they retained their independence until the 1590s.

The Anglo-Normans loved land, loved manipulating law

to achieve their ends, but most of all loved money and the power it brought. It

was the deBurgos who set about fortifying Galway in 1270 and building the Hall

of the Red Earl in 1273. The Hall is at the very nucleus of medieval Galway,

and served as the deBurgo administrative, judicial and customs collection

centre.4

The deBurgos energies however were dedicated to

consolidating and settling with planter families the territories east of the

Corrib and invited in mercantile families to administer and run Galway on their

behalf. This was to be their Trojan Horse moment.

In the Lynch family in particular, the deBurgos were

to encounter their mercantile nemesis. The Lynches from the beginning were true

‘merchant adventurers’ and also were well-connected to the Anglo-Norman

nobility. In 1274CE a

Thomas deLince was appointed provost or portreve of Galway and in 1280 he

married Bridget Marshall, the granddaughter of John Marshal, Marshal of Ireland.

Bridget’s great-great-grand uncle was Richard deClare, Strongbow, the original

Anglo-Norman robber-baron in Ireland.

In 1277,

either a brother or cousin of Thomas, a William deLench (deLince/Lynch) was

also appointed the collector of customs duties for Galway, primarily acting as Crown

agents for the Ricciardi bankers of Lombardy, to whom Edward I of England was

in hock. William deLench had to hand over these tolls to the Ricciardis in

Dublin. The arrangement between Edward I and the Ricciardi was to last until

1294 but is remembered in name of Lombard Street in Galway.

The deLinces/deLenches/Lynches, always opportunists, were to imitate the deBurgo’s and marry

into the local Gaelic gentry and ‘merchant-adventures’ of a previous era.

Thomas deLench was to have two sons, James and William. James gave rise to the

Crann Mór or senior branch of the family, later typified by the 19th

century ‘merchant adventurers’ Lynch-Blosse family of County Mayo. William

married Anne O’Halloran of the Bearna Castle Clan Fergaile O’Halloran’s and

interestingly 400 years later one of his descendents Stephen Lynch was to buy

out the last O’Halloran Lord of Bearna.

Like the O’Flahertys before them the deBurgos had two

major failings: one a tendency to kill-off competing members of the family and

secondly, a distrust and resistance to central or Royal government control of

their activities. This was to be their undoing. At the instigation of the

mercantile families of Galway, especially the Lynches, in Jan 1396 Edward IV removed

the right of the deBurgos to dictate the administration of the corporation and

instead formally established a Corporate Body subject to Royal approval. By

Richard III’s Charter to the City of December 1484 this marginalisation was

complete, and the deBurgos – again like the deBurgos had done to the

O’Flahertys and O’Hallorans 200 years earlier – were deliberately excluded from

the city. The Lynches, and the other mercantile families, not unlike the Medici

in Florence, the Sforza in Milan, the Dandolo of Venice, had gained complete

power to dictate the destiny of the City.

THE HALL OF RED EARL – WITNESS TO HISTORY

The building of walls to enclose the town of Galway had

been started in 1270 by Walter deBurgo and following his death in 1271, were continued

by his son Richard Óg deBurgo, known as the Red Earl. Part of this expansion

included a decision to build a separate manorial hall to the castle, thereby

putting a distance (albeit a very short one) between the residential and the

administrative. The castle in Galway to all intents and purposes served as the

deBurgo’s “townhouse”, given that their main concerns were appropriating land

away from Galway in the remainder of Connacht, they had their main castle or

caput at Loughrea. It is known that Richard Óg never spent much time in Galway

but because the Hall was completed in his lifetime it came to be called after

him.

The Hall housed both the customs collection office

and town administration, as well as being the site for the Town’s judicial

Hundred’s Court. Importantly, it also served as the location for large banquets,

and these must have been extensive and gluttonous affairs, judged by the amount

of food-related finds uncovered during the archeological excavations (See

Hackett & Delaney in References below). The hall completed about 1273, was

built on fairly shallow foundations, appears to have been of a two story type

with the main hall above, and a necessary kitchen and storage area below, with

also perhaps had a cramped and basement dungeon. The Hall in effect became

Galway’s first purpose-built Tholsel.5

When the deBurgo’s invaded and planted Connacht they

had, given their Royal patent, to hold and administer five cantreds of that

appropriated land for the Crown. None of this reserved land included property

in the town of Galway and as a consequence the city became the personal fiefdom

of the deBurgo family, who then set about establishing a city-state.

By 1333 the adjoining DeBurgo castle (“the stone

house”) of Dhun Bun na Gaillimhe seems to have fallen into disrepair, and its

masonry used elsewhere but as mentioned earlier, from the time of Richard Óg

deBurgo’s death in 1326 it had been little used in any event as a residence,

given that most of his surviving children were girls and had been married off

out of Connacht.6

The Hall continued to carry on its functions with all

customs, murage (wall-building) and judicial functions, administered by a

prescriptive corporation, appointed by and fully controlled by the DeBurgo

family or their descendents. These included the family of Richard Óg’s uncle

William Óg de Burgo (founder of the McWilliam Íochtar Bourkes of Mayo) and those

of an illegitimate half-brother of his grandfather Richard Mór (the McWilliam

Uachter or Clanricarde Burkes). Galway and the Hall fell into the remit of the

Clanricarde branch of the family.

The Hall however in structural integrity appeared to

follow the fortunes of its founder family intimately and in the 1330s,

coinciding with the cracks appearing in the DeBurgo legacy caused by the

internecine DeBurgo or Burke Civil war of succession, additional external buttresses

and central pillars were added to support the poorly built building. This was

an important development because of the increased demand or load on the

building caused by Galway being granted Kings’ Staple, or Royal Custom’s

clearing-house, in 1375. Although the Staple was revoked two years later the

remedial works had saved the Hall from falling down.

On the other hand Galway as a corporate entity, as a

trading entrepot was thriving but as a consequence of the deBurgo Civil war the

control of the Hall’s functions was beginning to slip from the deBurgo’s grasp.

In 1396 Richard II granted a Charter to the city, which established a Corporate

Body and a Sovereign to be appointed as chief administrator instead of the deBurgo

provost or portreeve. This was resisted strongly by the deBurgos and it was not

until 1434 that a Sovereign (an Edmund Lynch) was in place, around the time

that Cosimo de’ Medici came to power in Florence and the Sforza’s in Milan.

Like the de’ Medici and Sforza the mercantile

families of Galway, the Blakes, Kirwans, Skerrets and Lynches were becoming

stronger and increasingly resented the deBurgos involving ‘their’ town (and

their revenue streams) in deBurgo disputes with Royal governance. In addition

to this most of the leading families had built or were building their own

castellated “townhouses” from which much of the town’s administration was being

carried out depending on which family was Sovereign. Apart from the judicial

and ceremonial functions of the Hall of the Red Earl much of its “power” remit

had been removed.

In 1464 a Charter of Edward IV transferred all

decisions in regard to access to the town to the Sovereign and burghers and

thereafter as Amanda Hartnett (see references at end) has pointed out “the

prime directive of the mayor and council of Galway was to protect the

exclusivity of their status group.” This mercantile takeover of power

particularly applied to the de Burgos.

The status of the Hall during this time is a little

uncertain. There was a major fire in Galway in 1473 in which much of the town

was destroyed and there is little or no information as to whether the Hall was

caught up in the blaze and perhaps had to be repaired again. The town appeared

to recover quickly but this recovery appears to have been fully to the credit

of the ‘Tribe” families rather than any help received from the deBurgos.

Resentment simmered and by 1484 a Charter of Richard III confirming previous

Charters and the legal status of the Galway Corporation took the specific step

of excluding the McWilliam Burkes (deBurgos) of Clanricarde from having any

power within the town. Henceforward a Mayor instead of a Sovereign would

control the town, and in 1485 a Pierce Lynch was appointed Mayor (who else!) This

exclusion of the deBurgo’s was again reaffirmed in 1543 when Sir William de

Burgh was created the Earl of Clanrickard by Henry VIII, a condition of which –

petitioned hard for by the city Corporation –stated specifically that the Earl

would henceforth not ‘claim any thing whatsoever’ in the town ‘forever’. At

this stage the mercantile City tribes were at their peak, and had used their

new found wealth to buy estates and build castles on the territory surrounding

the city.

The deBurgos may have been gone but the Hall

continued in ceremonial use, at least until 1524 when a peace treaty between

Galway and Limerick over a commercial dispute was signed there. By 1550 however

the Hall appeared to be in ruins. Perhaps another fire had destroyed the roof and

it was not felt that it was worth repairing. In addition to this the needs were

expanding. A decision was made by the Corporation to erect a new Tholsel and it

is recorded that a James Óg Lynch, a mayor of the town in 1557 commissioned at

his expense, close to the Shambles, the east side of the new Tholsel and two

years later the building was completed by his relative Dominick Lynch. The

‘new’ Tholsel contained prison cells below, shops and a toll-booth on the

ground floor and the courthouse and corporation administration rooms on the

first floor.

The same Dominick Lynch petitioned the Privy Council

in 1566 to build a school on the site of the Hall, known by this stage as the

“Earls Stone” or “cloch-na-hiarla”, but this plan did not come to pass and by 1585

the ruined Hall had become an Iron smelting works.

Adapted from: Daly D. 2004b Courthouse Lane (97E82): Excavation. In Archeological Investigations in Galway City, 1987-1998. Fitzpatrick E, Walsh P, O’Brien M, eds. Wordwell Ltd., Bray.

But change was afoot both religious and secular in

Galway. Henry VIII’s break from Rome,

his becoming the first King of Ireland since the last Gaelic High King Rory

O’Connor in 1193, and the dissolution of the monasteries drove a “faith or

favour” wedge between Galway’s tribal families. In addition to this, the City itself

was coming under pressure. Elizabeth I created the Presidency of Connacht in

1569 and the Province was divided into Counties shortly afterwards. This was

for the purpose of imposing and creating a single taxation system rather than

the multiple levies imposed and collected by feudal overlords, both Norman and

Gaelic. In 1585 the Composition of Connacht confirmed this shiring and all of

the Gaelic clan’s, including the O’Flahertys and O’Hallorans of Iar Connacht

and the Anglo-Norman Burke/Bourkes/deBurgos of East and North Connacht were

brought under a centrally Crown-controlled County administrative structure,

nearly 500 years later than it had occurred in the rest of the British Isles.

The new County administration was to take precedence over the City and these

functions were removed to Loughrea. The County azzizes were held alternatively

between Loughrea and Galway and in 1610 the County moved into the deserted

Franciscan friary on St Stephen’s island outside the City walls.

In the same year James I granted a new Charter to the

city, which created a new “County of the City”, a liberties that stretched two

miles in all directions from the city walls, except the land of St Stephen’s

Island (where the new County of Galway courthouse was housed) and St

Augustine’s Fort which were to remain the property of the County of Galway, and

not of the County of the Town of Galway. A new Guild of Merchants was

incorporated and Ulick Lynch became the first Mayor and in 1637 a decision was

made to erect a new Tholsel.

In 1651 the famous Pictorial Map of Galway shows two

“shell” buildings. The first was the unfinished new or third city Tholsel close

to St Nicholas’ Church and the second was the ruin of the first Tholsel, the

Hall of the Red Earl. The following year on the 12th April 1652 Cromwell’s

forces marched into the city, after a siege of 8 months, and soon

disenfranchised, displaced or destroyed many of the mercantile families, who

moved or were moved to estates in the County, and planted the city with new

settler Protestant English. The Corporation was abolished and the City-State of

mercantile adventurer’s at an end.

Cromwell’s administration destroyed all of the

Franciscan Abbey buildings apart from the Church, including the priory where

the County Courts were held, and moved the Courts to the pillaged Church. In

1689 the Friars returned to take possession of the Church and the Courts needed

a new home. This requirement spelt the final end for the Hall of the Red Earl,

and its witness to the city-state that once was Galway. The walls were pulled

down and the new County Courthouse was erected on the site and completed by

1694. It would serve as the County Courthouse for about 100 years until 1812 when a new Courthouse

was built on St Stephen’s Island and which remains in operation today.

FINALE.

The mercantile adventurers who had created the

city-state were scattered to the four winds, to become merchant-traders (even slavers!) in the Caribbean, merchant-traders in France, merchant-adventurers in the

Middle East. Today the glass-canopied interpretive centre protecting the Hall's archeological remains reflects the change

in Galway’s direction. It is entered from a laneway that was once called The

Earl’s Lane when the city was an independent City State, then Courthouse Lane when the City was subject forever after to central control, and now Druid Lane in honour of the Theatre

Company across the road which has helped position Galway as a capital of

culture… a capital of Tourist-Adventurers in a new age of selling experiences

rather than hides or hogs of wine.

Would the O’Hallorans, O’Flahertys, deBurgos, Lynches,

Nolans, turn in their graves if the could see where the city was heading?

Not at all, I suspect. I live on land that was once part of the territory or túath of the Clan Fergaile, indeed it is part of what once was the óenach of the O'h-Allmurhain sept, the O'Halloran castle of Bearna; land that has always been subject to a bartering of its destiny, depending on the fortunes of its owners. It is land that was in the 19th century in hock by the Lynches to the Rothschild bankers in London; in the 18th century in hock to Whalley, one of Cromwell's officers; in the 17th century in hock by the O'Hallorans to the Lynches and so on back into the mists of time. When I am walking the dogs I walk the same paths those "merchant-adventurers" took and, listening to the sound of ages, I imagine the oaks whispering,

"No, they would not be too bothered about the direction the new Galway is headed, they would just have found a way to turn a penny."

That is the true nature of a City-State. Where the Hall of the Red Earl is concerned, and its position at the heart of that state, I suspect that those merchant-adventurers who have gone before would all have appreciated the legacy of the Hall but without any significant nostalgia attached.

"No, they would not be too bothered about the direction the new Galway is headed, they would just have found a way to turn a penny."

That is the true nature of a City-State. Where the Hall of the Red Earl is concerned, and its position at the heart of that state, I suspect that those merchant-adventurers who have gone before would all have appreciated the legacy of the Hall but without any significant nostalgia attached.

NOTES: GAILLIMH ETYMOLOGY

1.

As pointed out

by James Hardiman in his seminal 1820 History of the Town and County of the

Town of Galway there was no real etymological consensus in the early 19th

century as to how or when Galway derived its name; or whether the town gave its

name to the river delta on which it is situated – the river that connects Lough

Corrib to the sea – or visa versa. Even today, that most modern of

encyclopaedias – Wikipedia – perpetuates an 18th Century

determination by Charles Vallancey of the city’s name as being derived from “galmhaith”, an Irish compound word he

had ‘invented’ and which according to Vallancey meant “stony ground”.

Vallancey, an

English military surveyor and amateur philologist whose work later experts

considered to be absurd and who decried Vallancey as having ‘wrote more

nonsense than any man of his time’. It is true that from a geological

perspective the river is rock filled but the etymological derivation is

entirely without foundation!

From an

etymological perspective gaill is and

has been the Irish Gaelic for “foreigner” and has been applied since the first

native Celtic speaking inhabitants referred to strangers from overseas, in

contrast to the Gael familiars. The

word was later applied, particularly in the earliest Irish written records to

the Norse (Fionn Gaill or Fair Haired

Foreigners) the Danish (Gaill Dubh or

Black Haired Foreigners) Viking invaders, as well as to the Anglo-Normans and

later English.

The ending

attached to the noun is –imh, an old

Irish plural suffix. Thus it was the

nature of the inhabitants that defined Galway’s name, not the nature of its

geography.

NOTES: THE O'HALLORANS

2.

Organised

tribal migrations, reflecting the westward displacement caused by tribe after

tribe pushing out of the Eurasian steppes, were to follow the isolated pockets

of journeymen and tribal groups such as the Érainn or Belgae (?Fir Bolg) (c.500 BCE), the Laigin (c.

300 BCE) and in particular the Góidel (c. 200 BCE) from south-western France

and northern Spain (the Milesians) arrived. They brought not so much a similar

language (it was their Celtic that was modified by the already thriving Irish

Celtic language not the other way round) but more importantly their

well-developed tribal sense of ancestry, of hierarchy, of laws and customs as

well as the propensity for implosion that was to dictate the evolution of

Gaelic society.

As a

consequence of these successive acquisitive Celtic “tribal” migrations and

society structure Ireland became a patchwork of “carved-out” petty and small

territorial tuáth or “kingdoms” each

jostling for supremacy based on what has been called a “geography of lineage”,

a kinship to a supposed common ancestor; and each generally undone by that

kinship and a very recurrent Gaelic fault-line of internecine strife.

By about 100

C.E. the territory to the west of Galway and also the territory to its

immediate north-east were under the control of the Delbhna Tir dha Locha (the MacConraoi and O’Heney tribes) and the Delbhna Cuile Fabhar of Maigh Seola

respectively, who were subject to the Garmanraige clan (of Fir Bolg descent) of

the Cóicead Ol nEchmacht, the ancient territorial name for what is now the

province of Connacht.

Farthest west,

existing on the Atlantic coast and displaced from the Galway hinterland despite

intermarriage with the Delbhna, were another early tribal group known as the Conmhaícne Mara (who have given their

name to Connemara), descendants of the Fir Bolg tuath mhac nUmhoir, who were dominated by the O’Cadhla (O’Kealy)

clan. Their isolation was also their protection from 200BCE to 1200CE.

To the

south-east of the Cóicead Ol nEchmacht

(Connacht) Kingdom and stretching as far as the western banks of the Shannon

was another Fir Bolg dynastic territory Aidhne.

Around 300CE

the Uí Maine from Ulster crossed the Shannon and invaded Aidhne from the

north-east. A short time later the Connachta tribal federation, descendants of

the High King of Ireland Conn Cétchathach, crossed the Shannon River and

skirting the newly acquired territory of the Uí Maine appropriated the

remaining lands of the Aidhne before moving northwards along the eastern banks

of the Corrib to invade the territory of Cóicead Ol nEchmacht. The Connachta

consisted of the three junior branches (the Uí Briúin, the Uí Fiachrach, Uí

Alill named after the half-brothers of Niall of the Nine Hostages) of the Uí

Neill dynasty, who had claimed the High Kingship of Ireland at Tara.

The Uí Ailill

settled on Aidhne lands close to the Shannon but were eventually subhumed by

the Uí Maine.

After

subjugating the Ol nEchmacht

federation, the Uí Briúin Ai and Uí Fiachrach dynasties became Kings of Ol

nEchmacht (but renamed Cúige Chonnacht

– the “fifth” of the Connachta) around 482CE and established Ráth Cruachan in Co. Roscommon as the óenach tribal assembly site and royal

residence. As was the wont of most Gaelic tribes, by the mid-6th

century the Uí Bruin and the Uí Fiachrach septs began fighting for overall control

of Connaught and in 680CE the Uí Briúin came to ascendancy and were then called

the Uí Briúin Ai.

The Uí

Fiachrach as losers in this power struggle were subsequently restricted to the

last remaining westernmost territory of the Aidhne and thereafter they became

known as the Uí Fiachrach Aidne.

Immediately

north of the Uí Fiachrach Aidne, because the main body of the Uí Briúin Ai were

located in the north-east of the province where their energies were directed in

preventing more invasions from the North, an administrative sub-kingdom of the

Uí Briúin Ai was established to the east side of the Corrib, on the territory

previously held by the Delbhna Cuile

Fabhar and called Uí Briúin Seola.

All dynasties

evolve. By 950 CE the Ó’Conchubhair

(O’Conor) clan had become the dominant force of the Uí Briúin Ai and as such were proclaimed Kings of Connacht in 967CE.

Their powerful ascendancy also meant that they became High Kings of Ireland in

1119CE.

Equally

dynastic change occurred in the sub-kingdom of Uí Briúin Seola, controlled by the Muintir Murchada grouping of clans since 848CE. Although subject to

their kin, the O’Conor King’s of Connaught, the Ó Flaithbertaighs (O’Flahertys) came to be the dominant clan of the

Muintir Murchada and around 993CE became the tigerna or Lords of the Uí Briúin Seóla oireacht, a túath controlled from Lough Hackett near Tuam, Co.

Galway and consisting of most of eastern shoreline of Lough Corrib. In

addition, in response to the Viking incursions that had begun in 807CE the

O’Flahertys established a maritime force that was based on the islands of Lough

Corrib (Orbsen).

The intrigues

and murderous remit of Roman, Byzantine or early Ottoman ruling families were

child’s play in comparison to the poisonings, blinding’s, assassinations

carried out by Irish clan families against each other. Despite the ties and

owed loyalties of kinship the O’Flahertys, a particularly belligerent clan,

were determined to usurp total control of Connacht from the O’Conors. From

945CE they had also styled themselves Lords of Iarthair Connacht, indicating that they already dominated the clans

(McConrai and O’Heynes) to the immediate west of the Corrib, and emboldened by

this increasing power as well as their maritime forces tried to depose Aedh

O’Connor, the King of Connaught in 1048CE.

Shortly

afterwards the O’Conors rallied, defeated and beheaded Rory O’Flaherty and banished

most of the O’Flahertys from the greater portion of Maigh Seola across the Corrib. Furthermore, in order to protect

themselves, the O’Conors moved the Royal seat from Ráth Cruachan in Roscommon to Tuam on the edge of Maigh Seola, to

keep a wary eye on any renewed dynastic ambitions of the O’Flahertys.

In 1092CE

however, this “close monitoring” appeared to fail and an O’Flaherty became King

of Connaught after blinding – making him unfit for kinship – the O’Connor

incumbent. This putsch ensured that the O’Flahertys recovered some of their

previous held territories of Maigh Seola and this was described in the Annals

of “Crichaireacht cinedach nduchsa

Muintiri Murchada”, written in the time of the briefly held O’Flaherty

kingship, as being a Tract within the

territory of the Muintir Murchada. Although a very much reduced túath its importance as the spiritual

home of the O’Flaherty’s to the clan was inestimable. Its óenach or assembly place was at Óenach

Dhúin, a mixed ecclesiastical and secular enclosed area, on the shores of

the Corrib and known today as Annaghdown.

By 1106CE the

O’Conors had not only recovered the Kingdom of Connacht from the O’Flahertys

but had also become High Kings of Ireland. Turlough O’Conor ruled for 50 years

but his ascendency, owed much to his uncle an O’Brien of Munster. O’Conors

determination to eradicate all other competing Uí Briúin genealogical

histories, laid the seeds for the future conflicts between various O’Conors but

also between Connaught and Munster. The relationship of Turlough O’Conor to an

O’Brien of Munster also later provided the Anglo-Norman de Burgos with a

pretext to invade Connaught in the 1230s.

The O’Flahertys

however had made use of their time after being banished westwards across the

Corrib and using their resources came to fully dominate the nearest tribal

areas to the Corrib of Gno More, Gno Beg and Ballinahinch,. They then used their power as Lords of Iar (West)

Connacht to become indispensible to the O’Conors; the O’Conors perhaps

approving of Godfather Michael Corleone’s adage “Keep your friends close but

enemies closer” to be a wise move!

In 1119CE

Turlough O’Connor had split the O’Brien Kingdom of Munster into two halves,

Thomond and Desmond and soon the O’Conors and the O’Flahertys were fighting

side-by-side in trying to deal with revenge incursions from Munster. In 1124CE

Turlough O’Conor installed Conchobhar O’Flaherty as governor in the newly built

O’Conor castle and enclave of Dún Bhun na

Gaillimhe (Fort at the Mouth of the Galway River) in order to protect his

southern flank. In 1132 Cormac Mac Carthaigh of Desmond came by sea and

demolished the castle of Dún Bhun na

Gaillimhe and plundered and burnt the surrounding town. The following day

in a further battle at An Cloidhe (The Claddagh) Conchobhar was killed.

In addition to

a secular control of the territory of Gaillimh and surrounding districts the

O’Flahertys were also beginning to exert ecclesiastical control. By 1200 CE the

secular Gaelic clan control of the túath territorial areas in Ireland was being

severely undermined by the increasing power, wealth and ecclesiastical

influence of disparate monastic foundations. A hierarchial ecclesiastical

diocesan and parish structure was finally imposed on this motley group of

monasteries at the Synod of Ráth Breasil in 1111CE and Kells-Mellifont in

1152CE. In 1150CE the monastic centre of Annaghdown, which had been founded in

the 6th century by St Brendan the Navigator for his sister Briga,

evolved into Annaghdown Diocese, which in addition to Maigh Seola then assumed

administrative control for parishes both west of the Corrib in Iar Connacht and

south of the Corrib in the territory of the Clan Fergail.

In 1202CE

Murchad O’Flaherty became the second bishop of Annaghdown and in 1223CE, in

line with the Pope Gregory VII instigated church reforms sweeping across Europe

and influenced by St. Malachy, he invited the White Canons or

Premonstratensians (Strict Interpreters of the Rule of St. Augustinian) of the

Tuam monastery (founded c.1203 as offshoot of main Prémontré Abbey) to establish

a “daughter house” monastery in Annaghdown. Unusually, an earlier Arroasian

(another Order very similar to the Premonstratensians following the Rule of St.

Augustine) Convent had been established by Turlough O’Connor at Annaghdown in

1144CE so, with the arrival of the White Cannons, Annaghdown became a

double-monastery site. The convent was known as St Mary of the St Patrick’s

Gate.

As the 12th

century drew to a close not only were the O’Flaherty and O’Conor families

trying to kill members of their own families off but they also renewed their

open hostility to each other. In 1207 Cathal Crobhdearg O’Conor once again

tried to exile the O’Flahertys across the Corrib by giving their territory to

his son Aedh (Hugh) O’Conor and in 1230 it was the conflict between the two

grandsons of Cathal Crobhdearg for the Kingship of Connacht that gave the

Anglo-Norman de Burgos a pretext to invade the province.

3.

South of Maigh

Seola, and the secular and ecclesiastical O’Flaherty óenach of Annaghdown, another Uí Briúin clan – the O’Halloran’s –

had their túath. The túath was known

as the Clan Fergail.

Clan Fergail

owed their lineage to Allmhuran (died c.450CE), whose name derives from the

Gaelic allumhaire: “One who imports”.

By 800CE the O’h-Allmhurain or

O’Halloran descendants of Allmhuran – and kinsmen of the O’Flaherty’s through

Aongus brother of Duach Galach, the

first Christian Uí Briúin King of Connacht – had become established in the area

around present day Galway city where they had partially displaced the Delbhna Tir dha Locha from the eastern

half of Gno Beg.

The O’Hallorans

came to fully control a territory of 24 town-lands centered on Gaillimh and became known as Clan Fergail, or túath of the Men of the Foreigners (or Foreign Merchants depending

on which derivation of gaill you

accept). With the Atlantic waters of

Galway Bay acting as its southern border the Clan Fergail territory extended about 6 km from Roscam in the East

(where the O’Antuiles (the O’Halloran innkeepers) and O’Fergus (the O’Halloran

land managers) clans were subordinate) to the village of Barna 6km to the West.

It also extended about 6km northwards to the southern shore of Lough Orbsen

(Lough Corrib) where it adjoined the O’Flaherty’s territory of Maigh Seola at

Claregalway.

Irish Gaelic society,

unlike the English Anglo-Saxon society, did not have a tradition of established

coastal “wics” or emporia. They preferred to conduct their trading at the

usually inland-situated tribal óenach

assembly and fair sites. Allmurhan may have got his name (nickname!) as an

“importer” from deliberately conducting trade with (or living within) a

foreigner’s coastal enclave established at Gaillimh. As mentioned earlier this

could have been, as early as 200CE as a Phoenician outpost but certainly by

650CE Gaulish traders from Acquitane and Bordeaux were brining wine to Ireland.

It appears

that Allmurhan’s descendants, the Clan Fergail (O’Hallorans), spreading out to

control the area surrounding the coastal wic at Gaillimh, were always traders

rather than fighters. After making an early military alliance with the O’Flahertys

to deal with Viking raids from 807CE onwards, the O’Hallorans destiny was to be

entwined with that of the O’Flaherty Lords of Iar Connaught, following their

initial deportation across the Corrib in 1051. In addition, c.1200CE, the new

diocese at Annaghdown, under the control of an O’Flaherty bishop, was exerting

an increasing temporal as well as ecclesiastical control of the Clan Fergail

túath. This association is manifest when in 1230CE or so the O’Hallorans

established a “daughter-house” Convent of the Arrosian-Premonstratensian

Abbey-Convent of Annaghadown in the Claddagh, the fishing village on the

opposite western bank of the river to Gaillimh. The convent was known as St

Mary of-the-Hill and its site is occupied by the Dominican Church today.

Following the

defeat of the O’Flahertys by the Anglo-Norman de Burgo’s in the 1230s the

O’Flahertys and O’Hallorans were dispossessed of most of their remaining

territory and land-holdings close to Galway and the Corrib and were further

displaced further and further westwards and north-westwards to the most remote

parts of Connemara. The O’Hallorans did manage to hold onto their main castle

at Bearna close to the city and also a townhouse in the emerging walled

city. Despite further conflict with the

de Burgos in 1248, to a great extent, until the Composition or Shiring of Connacht

in 1585, the O’Flahertys and O’Halloran’s were left to control their own

destinies.

By the early

years of the 16th century the O’Flahertys had built a string of

defensive castles at Aughnanure, Ballinahinch, Doon, Moycullen and Bunowen to

control their territories in Iar Connacht. Complimenting their liege-lords the

O’Hallorans had, in addition to holding on to their main stronghold on Rusheen

Bay near Bearna, had also built the O’Hery castle on Lough Lonan (Lake Ross)

near Moycullen and Renvyle Castle on the Renvyle peninsula. The O’Hery castle

was taken from the O’Hallorans by the O’Flahertys in the 1580s.

In 1594 following

the Composition of Connacht Dermoid McShane O’Halloran of Bearna castle

transferred his title to the Castle of Renvyle and most of his property in the

adjoining townlands of Ardnagivagh and Tulaghmore to his cousin Edmund

O’Halloran a merchant of Galway.

Between 1606

and 1638 Dermoid and Edmund O’Halloran’s heirs sold Renvyle Castle and the

remaining O’Halloran lands surrounding Clegan to the O’Flahertys. With their

western holdings disposed of to the O’Flaherty’s the remaining O’Halloran

possessions closer to Galway were soon to be lost to another, and newer,

powerful mercantile family, the Lynches. In November 1638 Stephen Lynch

obtained the title in the Court of Chancery to the O’Halloran castles of Bearna

and O’Hery in Lough Lonan for £410 19s 8d. in lieu of a debt owed to him by

Edmond O’Halloran.

This initial

Lynch possession was short lived. In 1652 the Cromwellian Act of Settlement

confiscated the Lynch lands of Bearna and Moycullen and granted them to John

Whaley, one of Cromwell’s officers. However, in January 1681, following the

Restoration Explanation Act of 1665, Nicholas fitz-Marcus Lynch of Bearna was

able to buy back the large estate from Whaley for £644 13s 9d and he then sold

on a small portion of it (lands in present day Poolnaroma and Knocknacarragh)

to Finian Halloran for £83 4s 2d. Finian Halloran subsequently leased out the

lands to a William Brock of Clare for 31years.

The O’Halloran

legacy of the Connachta tribal federation conquering of Connacht in the 5th

Century and the establishment of the Clan Fergail in the 8th Century

was by 1700CE well and truly diminished although the territorial legacy of the

Clan Fergail túath was to be maintained in the future development of the Town

and the County of the Town of Galway.

4.

Following his

deposition in 1167CE as King of Leinster, by Rory O’Conor the High King of

Ireland, Diarmaid Mac Murrogh asked Henry II of England for help in recovering

his Kingship and in 1169 a group of Anglo-Norman mercenaries landed in Ireland to

help MacMurrogh. In 1171, following MacMurrogh’s death Henry II organised a

more formal invasion and the Anglo-Norman appropriation of Ireland began in

earnest.

In 1185CE

Henry II dispatched his son, Prince John to Ireland as a potential King of

Ireland (a move blocked by the Pope) to exert Royal authority over the earlier

wave of Barons. He landed with 300 knights and a team of administrators and was

accompanied on this expedition by a knight from Norfolk, a William Fitz-Andelem

deBurgh (deBurgo). Following John’s inglorious departure deBurgo decided to

stay and make his fortune in the country. John’s personal behaviour on that

first expedition had further alienated many of the already established 1169

Anglo-Norman arrivals from Crown authority and he had to return again in 1210

as King to crush a revolt by these Barons. William’s younger brother Hubert

deBurgo also later entered King John’s service and rose to become Earl of Kent

and Justiciar (equivalent to Prime

Minister today) of England in 1215CE.

In a very short space of time, with King

John’s patronage, the deBurgo family had gained prominence in both England and

Ireland. In 1195CE William deBurgo was granted lands, by King John,

in Limerick and Tipperary. He promptly married the daughter of the O’Brien King

of Munster and was able to use the bitter enmity of the O’Brien’s and O’Conor

dynasty of Connacht to pursue speculative forays into the province. A further

opportunity arose when Cathal Crobhderg O’Connor invited William to help supress

a succession revolt within his own family in 1201CE. This was initially

successful, but with help from an O’Flaherty (who else?) William plotted to

assassinate O’Conor. The plot was discovered any many of deBurgo’s retinue were

killed in a pitched battle by the O’Conor forces. The following year however

William returned, took revenge for the previous defeat and began to style

himself Lord of Connacht. Henry II had originally granted deBurgo title to the

Province but then withdrew it because he was uncertain whether he could control

the outcome. William died in 1205CE, probably from leprosy.

In 1215CE King

John granted William’s son Richard Mór de Burgo, and his heirs, the Kingdom of

Connacht and this edict was confirmed by Henry III in 1218, with the provisio

that it was not to take effect until the death of Cathal Crobhdearg O’Connor.

Cathal died in 1223 and was succeeded, after yet another internecine dispute

with Cathal’s brother Turlough, by his son Aedh (Hugh) MacCathal O’Conor. Aedh

was subsequently assassinated by Geoffrey de Maurisco and Turlough O’Connor,

brother of Cathal Crobhdearg restored to the throne.

In 1226CE,

with the help of his uncle Hubert who remained Justiciar of England under Henry

III, Richard Mór de Burgo was appointed Justiciar of Ireland and promptly went

about deposing Turlough O’Conor from the Kingdom of Connacht and installing

Fedhlim O’Conor, another brother of Cathal Crobhdearg, instead. Fedhlim was not

a puppet to the deBurgo’s however and set about resisting their attempts to

take over the province. In 123oCE Hugh O’Flaherty, the Lord of Iar Connacht and

Governor of Gaillimh declared himself in favour of Fedhlim’s resistance and

fortified himself in the castle of Dún Bhun na Gaillimh. Richard Mór deBurgo

promptly besieged the castle but the siege was lifted after a relief force from

another Aedh O’Conor (Feidhlim’s son) arrived. In 1232CE however deBurgo

rallied, reinvaded Connacht, defeated Feidhlim, took him prisoner, and deposed

him from the Kingship of Connacht. Richard Mór took the Castle of Galway after

a short siege and immediately set about improving and extending its structure.

After a brief interlude, when an escaped Fedhlim retook the castle, the de

Burgo’s were to hold sway.

With Galway

and their southern flank protected the deBurgos then set about appropriating

the land to the east side of Lakes Corrib and Mask, planting settler families

and building a string of defensive castles. In 1235CE Richard Mór deBurgo

expelled the O’Conors from most of Connacht and also for the final time, the

O’Flahertys from Maigh Seola and the islands on Lough Mask and Lough Orbsen

(Corrib). Thereafter deBurgo styled himself 1st Lord of Connacht and

the O’Flahertys concentrated their energies on Iar Connacht. Richard Mór

deBurgo died in 1241CE and was succeeded by his son Walter, who subsequently

was created 1st Earl of Ulster in 1264CE.

In 1271 Walter

deBurgo died in the original (but extended and rebuilt on many occasions)

O’Conor castle in Galway and was succeeded by his son Richard Óg deBurgo, the 2nd

Earl of Ulster and known as the Red Earl. At that point the castle served as a

residence, as well as a location for the Hundred’s court and toll collecting

office. The tolls in 1270 amounted to about €900,000 in today’s value.

Richard Óg

deBurgo, with great energy, set about expanding and fortifying the city and as

part of this development he built what is now known as the Hall of the Red

Earl, at one corner of the old castle, to serve as the administrative, customs

and legal centre for both the city and the district, and separated from the

residential remit of the castle. The new hall would become in effect Galway’s

first Tholsel and was referred to that as such thereafter.

Caught up as

he was consolidating his power in the remainder of Connacht deBurgo knew he

needed to attract mercantile families and administrators to his new city, not

only to service and supply the planter families the deBurgos had settled in

Clan Fergaile and the remainder of East Connacht, but particularly to maximise

the flow of revenue into his coffers. The Normans wherever they went, England,

Outremar, Sicily or Ireland loved land, loved bending and shaping laws to suit

their own ends, but most of all loved money! As a necessity deBurgo went about

attracting families such as the Lynches, Martins, Brownes, Kirwans etc to come

and settle in the city. It was these early ‘town” families who, in later years,

would come to supplant the deBurgos and who would become known collectively as

the Tribes of Galway.

As a

consequence of a Crusade he had mounted in 1270CE by 1275CE Edward I of England

was in serious debt to the mercantile Bankers of Lombardy, and in particular

the Ricciardi of Lucca. As a trade-off the Ricciardi were subsequently

appointed by Edward to oversee all customs collection in his Kingdom,

particularly those governing the wool trade. Although Edward I’s control of the

deBurgos in Connacht was tenuous at most, this remit extended even to its

furthest western shores.

In 1274CE a

Thomas deLince (?Lynch – Hardiman is silent on whether deLince was the first

Lynch) was appointed provost or portreve of Galway and in 1277 either a brother

or cousin William deLench

(deLince/Lynch) was appointed the collector of customs for Galway, as agents

for the Ricciardi bankers of Lombardy. William deLench had to hand over these

tolls to the Ricciardi’s in Dublin. The arrangement between Edward I and the

Ricciardi was to last until 1294CE but is remembered in name of Lombard Street

in Galway.

Leaving aside

the “central” tax on the wool trade that was handed over to the Ricciardi on

behalf of Edward I, the economic value of Galway to the deBurgos as a

commercial and administrative centre was obvious when one looks at the enquiry

into the estate of Aveline, Walter deBurgo’s widow in 1283CE. At that stage she

was personally deriving £130 per annum (equivalent today of about €4,200,000)

from rents, concessions (the lease of the Hall of the Red Earl to the Hundred’s

Court etc.) and tolls in the city. In 1303 CE, following the demise of the

Ricciardi, a new standardised custom’s duty on all goods in and out of the city

of 3d in the pound (1.25%) was introduced.

Beyond the

immediate environs of the city events continued to unfold. In 1316CE the last

Gaelic kingdoms to the west of the Shannon were all but extinguished as

political and social entities when the deBurgos and deBerminghams annihilated

the Gaelic army at Athenry killing many of the nobility including the last

O’Conor King of the Uí Briúin, and the O’Kelly King of Uí Maine. It is notable

when one looks at the Annals detailing the Gaelic nobility casualties in the

battle that neither the O’Flahertys nor the O’Hallorans are mentioned. Wisely,

it appears they had stayed away from this “final” defeat in their sanctuary of

Iar Connacht, continuing to consolidate. Indeed the O’Hallorans, traders for

ever, managed to hold onto their castle and lands in Barna, very close to the

city until the 1600s and I suspect that it was because they had nominal title

to the fishing village of the Claddagh (where they had built an Abbey for the

Arroasian nuns), which controlled the Salt Water fishing trade and the supply

of fish to deBurgo’s “new” Galway town.

5.

For five thousand years tolls have been a feature of

mercantile adventure and profit. From the baggage trains bringing Lapis Lazuli

from one small valley in present-day north-eastern Afghanistan across the

toll-controlled rivers and canals of Mesopotamia (paying a specific toll tax

called the “burden”) and the Frankincense trade from south-eastern Arabia

(paying tolls at every camel-halt from Ubar to Gaza) to faience and fumigate

the deaths of Pharaohs to the Value Added Tax of most of today’s economies

merchants have paid those tolls, calculating the cost into their profit

margins.

The Greek word for a toll, telos means both an “end” and “tax” (thereby satisfying Daniel

Defoe’s idiomatic words “Things as certain as Death and Taxes, can be more

firmly believed” in his book The Political History of the Devil in 1726.

A telonion

was a Greek toll-house and there was a well-established legal principal of

exemption from custom duties known as ateleia,

an exemption that was later to feature strongly in the medieval control of toll

collection. The later Roman teloneum

derives directly from the Greek and as soon as the opportunity for trade

offered by the expansion of the Roman Empire under Caesar Augustus arose, many teloneum or toll stations were

established in designated customs jurisdictional areas, particularly during the

time of the Pax Romano between 70 and 190ce. The main toloneum in the larger

provincial towns and cities (caput) and

ports came under the control of the procurator in the West or the comes

commerciorum in the East and would be housed in the preatorium building, which

would also then house the combined administrative and judicial functions with

the collection of mercantile tolls. The high Alpine passes had their own

poll-stations called clusae.

The close proximity of the Roman empire to both

Celtic tribes such as the Belgae and the North Germanic tribes of Jutes, Angles

and Saxons in what is now Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein meant the adoption of

many Roman institutions of governance. In Saxon lands the teloneum evolved into

the Tol-sael, from Tol for Toll and saele for hall.

Around 449 ce the Jutes, Angles and Saxons migrated

into the vacuum created by the Romans retreating from Britain and Tolsaels were

established in the Saxon coastal and esturine wics or emporia (Lundonwic,

Gippeswic-Ipswich, Eorforwic-York etc) to service and tax the merchants and

also to serve as judicial and administrative centres for the developing towns

by incorporating initially the folk-mootes but later the more formalised

Hundred and Shire courts.

In later Anglo-Norman England, especially after the

separation of Church and State functions of the courts with the 1073 Writ of

William I Concerning Spiritual and Temporal Courts the Tolsaels became the Tolbuthes or later Tolbooths of Scotland

and the Tolseys of England. The most

famous and long-lived of the Tolsey courts were those at Bristol (confirmed by

a Charter of Edward III in 1373) and Gloucester.

In 1325 Glastonbury had a hall for holding tourns and

courts, under which was a gaol for holding prisoners and five shops paying an

annual rent of 30 shillings and a little shop or stall (tolsey) paying 6

pennies for receiving tolls at the time of fairs, a true reflection of the

evolved combined mercantile, judicial and gaol function of the Tolsey.

With the arrival of the Vikings and later Normans the

Tolsael hall that combined mercantile, administrative, judicial and gaoler

functions became known in Ireland as the Tholsel.

The Tholsel on the corner of Nicholas St. (now Christchurch place) in Dublin

was called the ‘new’ one in 1311 the original having been probably erected

shortly after 1171 (Henry II had granted Dublin to the ‘men’ of Bristol in 1164)

when the Welsh Norman invasion under Strongbow, The Earl of Pembroke took the

city. Later in 1343 there was a specific charter of Edward III granting

exemption from the portion of tolls due to the King so that the burghers could

repair the Tholsel and in 1395 a Geradus Van Raes was appointed keeper of the

Dublin Tholsel for life. He was granted the keep of both the upper and lower

gaol in that tholsel indicating an expansion in the imprisonment requirements.

6.

Inquisition

post-mortem of possessions of William deBurgo, Third earl of Ulster. (quoted in

Hardiman’s History page55)

REFERENCES:

Daly D. 2004b

Courthouse Lane (97E82): Excavation. In Archeological Investigations in Galway

City, 1987-1998. Fitzpatrick E, Walsh P, O’Brien M, eds. Wordwell Ltd., Bray.

DERHAM RJ. The

Galway Tholsel 1232-2015: A perambulation through 800 years of evolution and

revolution.

http://deworde.blogspot.ie/2015/09/the-galway-tholsel-1232-2015.html

DERHAM RJ

Rihla (Journey 46); Partry House, Co. Mayo, Ireland – The Lynches of Mayo and

Mesopotamia

http://deworde.blogspot.ie/2014/10/rihla-journey-46-partry-house-co-mayo.html

DÚCHAS NA

GAILLIMHE: Hall of Red Earl.

http://www.galwaycivictrust.ie/index.php/projects/27-hall-of-the-red-earl

Hardiman J.

The History of the Town and County of the Town of Galway. Dublin. 1820

Hartnett AM.

Legitimisation and Dissent: Colonialism, Consumption, and the Search for

Distinction in Galway, CA. 1250-1691. PhD Thesis. Univ. Chicago. 2010

Middleton N.

Early medieval port customs, tolls and controls of foreign trade. Early

Medieval Europe 2005 13 (4) 313-358

McNulty PB.

Genealogy of the Anglo-Norman Lynches who settled in Galway. 2010 J Galway Arch

Hist Soc 62, 30-50

O’Flaherty R.

West or Iar-Connaught. Ed. J Hardiman. Dublin. 1846

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)