Looking South West over Aillebaun Headland from Blakes (Gentian) Hill

Rihla (The Journey) – was the short title of a 14th Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar Ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling and somehow the title of Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos of many of the city and country journeys I have been lucky to take in past years.

This Rihla is about dreams, and delusions and the deep blue sea.

DAYDREAMS AND WET SOCKS.

Returning home with the dogs across the sandy beach that runs off the Aillebaun

headland I found myself having to quicken my pace before the incoming sea prevented

me from crossing the river that cascades through the barna gap of Rusheen Bay, a river which can disappear very quickly

beneath a flooding tide. Despite my hurrying I still had to, once across the

river, remove my Wellington boots to empty out the water of a miscalculated

transit and sit on a rock to wring out my socks. From my sodden vantage point

the grey-blue waters of Galway Bay were still, as they had been for the previous

week, untroubled by Atlantic swell or squall and in the distance, to the

south-west, the purple shadows of the Aran Islands lay at anchor on the

horizon, gently lapping against the sky.

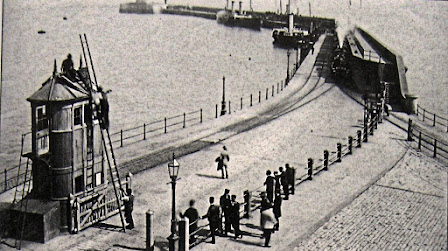

Imaginary Train coming in from proposed East Pier of

1911 Barna Deep-Water Transatlantic Port

As I day-dreamed on the notion of anchorage I realised that given a

different history, a different outcome of dreams, that instead of being perched

on a glacial discard, I could have been sitting on the hewn quayside of Barna’s

deep-water Transatlantic Port watching the bustle and groans of a busy modern

harbour winding down for the day. To my left a train would have been making its

way behind me with containers from the cargo terminal on Pier 1 while to my

right its companion engine would have been entering the tunnel beneath

Aillebaun brining tourists from the ocean liner docked at Pier 2 back from

their day in the city, in time for dinner.

Rusheen Bay

A chilling of the air brought me back to reality and the imaginary trains

suddenly derailed. The sun was setting fast and at this time of year the sunset

is sometimes sudden, brutal almost, the sky mutating from a brilliant amber to a

dirty grey in an instant: a rapid shift from daydreams to the stuff of nights. Beyond

Inis Meáin and the other Aran Islands on the horizon, are the depths of the

ocean, and in the chill of twilight I know that yet another storm will soon form,

and once again the waters and sky of Galway Bay will churn with its ferocity

and darkness.

As early as the 9th century Latin chroniclers and Arab

geographers began referring to the Atlantic Ocean beyond the Straits of

Gibraltar as the Mare Tenebrosum or Bahr al-Zulamat, both meaning “The Sea

of Darkness”. 1 As the Arab geographers would have it, where the

Atlantic was concerned, the “depth of darkness” below the ocean waves was

matched by the “depth of darkness” above those waves in the shape of billowing,

foreboding, storm-laden clouds coming rapidly over the horizon.

Whether it was 900 CE or 1900CE the Atlantic always seemed to have

associated with it a sense of adventure, but more often as not an equal

ignorance of its dangers…. and its vortex of shattered dreams.

DAYDREAMS AND GALWAY PORTS

In 1830 the Galway Docks and Canal Bill was passed with two aims in mind:

to establish and maintain a navigable canal between Lough Corrib and the sea,

and to improve and develop Galway Harbour to “facilitate and augment the Trade

of the Town and Neighbourhood.” The entire project was meant to have been the

responsibility of the Galway Harbour Commissioners but problems with managing both

the contract and the finance of the key inner harbour wet dock, caused a dispute

between the Harbour Commissioners and the Board of Works. The dock was not

completed until 1843 by which time the Board of Works had appointed a receiver

to collect the tolls instead of the Harbour Commissioners.

These problems with completing the inner dock also held up progressing

the canal element envisaged in the 1830 Bill. Work eventually began in 1848 on

the canal, which was ¾ mile long and whose construction included dredging the

Corrib, building a second wet dock at the Claddagh, five swivel bridges, two

quays and one very large lock. Managed entirely by the Board of Works, by that

time primarily as a famine relief scheme, the Eglinton Canal and its associated works were completed and

opened without much in the way of any fanfare in August 1852. 2

Claddagh Basin 1870

Terminus of Eglinton Canal

As early as 1830, Galway was identified as a possible location by the

Admiralty as a site for the main Packet Station connecting the British Isles

and North America, but any moves in this direction would not be possible unless

first, Galway was connected by rail to Holyhead on the East Coast and secondly,

development of the outer harbour as a safe refuge for ships took place. Despite

the completion of the Midland Great Western Railway into Galway,3

five months ahead of schedule by the contractor William Dargan on the 20th July

1851, progress on developing an outer harbour, suitable for handling the

transatlantic steamships, was constantly mired in vested-interest local,

national and British Isles politics, as thick as that of the mud that first had

to be dredged and as solid as the ship-breaking rocky bar or ledge right in

front of the new inner wet-dock gates which the contractor had failed to

remove.

Any development in these years had to be seen in the light of the

devastating effects of the Great Famine, caused by potato blight, between 1845

and 1852. In 1848 there were food riots in Galway. Between 1847 & 1848

11,000 people died in the city’s workhouse. In 1841 the population of Connaught

was approximately 1,418,859 but by 1851 it has been estimated that 239,529

(16.9%) men, women and children had died and 245,624 (17.3%) had emigrated. 4

As a consequence of the Famine the emigrant trade became a significant

part of Galway’s daily life and commerce. In 1851 alone 18,000 people from the

town and county left and between 1846-51, on just one of the emigrant routes

from Galway, 69 ships left for New York alone. A renewed effort was therefore

made to position Galway as a Transatlantic Port in the early 1850s. Much of

this effort pivoted on the personality and bravado of a Rev Peter Daly, who in

addition to being a parish priest was also one time Chairman of the Town

Commissioners, Chairman of the Harbour Commissioners, a board member of the

Midland Great Western Railway (MGWR)company and founder of the Royal Atlantic

Steam Navigation Company (The Galway Line) with J.O. Lever in 1858. 5

As part of his mercantile association with the Galway Line he proposed building

a new, and very elaborate, deep water Transatlantic Port off Furbo.

In 1852 the Rev Daly, as Chairman of the Galway Harbour Commissioners,

had also made submissions on behalf of the Harbour Commissioners to the

Admiralty Committee inquiring into the Suitability of Ports of Galway and

Shannon as Transatlantic Packet Station. This enquiry re-ignited the centuries

old – and still persisting if recent pronouncements on the building of a liner

port in either Foynes or Galway is noted – rivalry and mercantile jealousy

between Limerick and Galway when as early as 1377, the magistrates of Galway

were ordered not to extract customs duties from Limerick merchants, an

arrangement which was not operative in the reverse.6 The three Naval

officers commissioned to write a report for the committee felt that neither

Galway or the proposed ports on the Shannon estuary, with their current infrastructure,

were suitable as transatlantic ports but in November 1852 the Admiralty recommended Galway to the Board of Trade as

the packet station for transatlantic communication.7

Admiralty Pier Dover Built c1850s

A further report on the development of Galway Harbour as a Refuge

Harbour, was commissioned by the Admiralty in 1859, and three separate designs

were submitted for consideration. 8 A new Harbour Bill to finally

propel the development of an outer harbour incorporating the Mutton Island

causeway was passed in the Commons in 1861 but the clause looking to impose a

levy on the County of Galway to help pay for the development was rejected by

the House of Lords, despite the pleas of the Marquis of Clanricarde ( a deBurgo

descendent). The Board of Trade had approved the Galway Pier Junction Railway

Bill authorising the MGMR to build a branch line from Lough Atalia over the

Corrib and then down through the Claddagh to the Mutton Island causeway at Fair

Hill.

Building a Pier

As had been the case to date nothing really happened! The Rev Peter Daly

despite his industry was losing friends fast, at a religious, political, media,

landlord and mercantile level. Around the same time that the new Harbour Bill

languished, the main shipping line servicing the port and requiring a suitable

outer harbour to be built was in trouble. The Galway Line which had been

subsidised by the Royal Mail to the tune of £3,000 per annum to carry mail to

Newfoundland, became as Tim Collins has put it, “a heroic failure” due to

shipping disasters and scheduling deficits. Under pressure from the Cunard and

Inman Lines who started calling at Cork, and the development of transatlantic

cables, the Royal Mail contract for the direct Galway-North America service was

withdrawn in May 1861. In addition to this the Rev Peter Daly died in 1868 and

much of the local energy driving the development of an outer harbour

dissipated, or foundered like the Galway Line’s ship the Indian Empire on the

Margaretta shoal.

Approaching Galway Inner Dock 1872

In 1885 there was a further effort made to get the Harbour at Mutton

Island built but this time using convict labour. It was estimated that it would

take 450 convicts 20-25 years to complete the project. 9 Again in

1895 there was yet another attempt made but the projected cost had risen from

£155,000 (€21,266,000 in 2016 values) in 1852 (when the cost of laying down a railway line was £4011 [€553,000] per mile) to £670,000 (€79,560,600 ) in

1895.

DAYDREAMS AND BARNA TRANSATLANTIC DEEP-WATER PORT

After a decent interval to allow Davy Jones fully claim the restless soul

of the Rev. Peter Daly, spurred on by a pamphlet written by Richard J. Kelly, the owner of the Tuam Herald newspaper, a new evangelist contractor appeared on the scene,

ready to promote and develop a transatlantic deep-water port: Robert Shaw

Worthington.

Worthington was a Dublin-based railway construction contractor who first

came to attention as the contractor on Sallins-Blessington and

Blessington-Tullow connection for the Great Southern & Western Railway

Company, which were completed in 1885 and 1886 respectively, at the same time

that he completed the huge Robert Street Malt Store for the Guinness company.

He then went on to build the Cork and Muskerry Light Railway on time and on

budget in 1887-1888, the Loughrea & Atymon Light Railway for the Midland

and Great Western Railway Company(MGWRC) in 1890, and the Ballinrobe & Clarmorris Light Railway, again for the MGWRC in 1892.

In early 1891 Worthington was also contracted by the MGWRC to do the

preliminary surface work over the extensive boglands for the proposed Galway –

Clifden railway line, but he ran into conflict with both his workers, whom he

underpaid and who went on strike, and the MGWRC engineers. His foreman at the

time attributed the problem to the local Connemara men not being used to using

the short but wide “Navvie” shovel! In any event Worthington was not offered

the contract to build the railway proper and retreated for time back to Dublin.

However the even worse performance of Charles Braddock, who was awarded the

contract instead, managed to portray Worthington in a more favourable light and

in 1893 was contracted by the MGWRC to build the Achill extension of the

Westport line. This was completed in 1895.

With the completed Achill, Clifden and Galway Extensions

of the Midland & Great Western Railway Tourism began in the

West of Ireland. Poster c.1900

Worthington by this stage had developed grandiose ambitions, in trying to

match William Dargan, the doyen of the Irish Railway construction engineers. He

had developed a number of close personal and influential friendships with the likes

of the Prime Minister of Newfoundland Sir Edward Patrick Morris and the

barrister-owner of the Tuam Herald Richard J. Kelly. Both Morris and Kelly

strongly supported the development of a deep-water harbour in Galway to serve

in particular the shortest sail-time “Red-Route” across the North Atlantic to

Newfoundland. Armed with this support

and with start-up funding for a necessary Parliamentary Bill from the Chairman

of the Midland and Great Western Railway to the tune of £5,000

(€658,000) Robert Worthington returned to Galway in 1909 with a very solid proposal to

build and service a Transatlantic Port at Barna. He was welcomed with open

arms.

Galway's Deep Harbour Plans in Library of NUIG

Worthington was astute. He knew that the first item on the agenda, if a

Parliamentary Bill was to be successful, was to identify and get onside the

owners of the land that might be required, as well as the local mercantile

community. He formed the Galway Transatlantic Port Committee in 1910 and induced

the Bishop of Galway, Lord Killanin, the aforementioned Richard J. Kelly, and

Marcus Lynch of Barna, who was chairman of the Galway Harbour Commissioners, to

become part of that committee. The Committee also included Dublin and Galway

town commissioners as well as a representative from the MGWRC and was chaired

by Lord Killanin. The Committee went about submitting a required Bill for Parliament’s

consideration as well as contacting relevant bodies such as the county councils

in Ireland and the Prime Ministers of New Zealand and Newfoundland to get their

specific support for the proposal.10

The Committee also engaged the services of Arthur D. Hurtzig of the distinguished

engineering firm Baker & Hurtzig, who had, as engineering consultants, just

completed the Aswan Dam across the Nile. Hurtzig visited Galway in May 1911,

was met by Marcus Lynch and Col Courtney and subsequently submitted a design

proposal. Unfortunately the proposal appears to have stopped there. Despite

their efforts Parliamentary support for the scheme was not forthcoming, and having

been left on “the Table” for consideration it languished there for 2-3 years before

being finally abandoned when the Midland and Great Western Railway withdrew

their support in early 1913. Worthington was livid, and in a letter to the

MGWRC Board in July 1913, pleaded for financial help in supporting the

Parliamentary process and not the construction. He stated that he had the

construction costs of €1,500,000 (€200,000,000), pending Parliament passing the

Bill, available. 11

Although there is little documentation to back this contention I also suspect

the direct support of Marcus Lynch of Barna to the project was essential. In

1870 the Lynches of Barna owned 4,100 acres of land in Galway and by 1905 still

controlled most of the land where the servicing and building works area for the

projected port and west pier were to be located. Had the proposed port

proceeded it would have proved to have been an interesting set of negotiations to

free up the part of Lynch’s land required for the development.

In 1906 Marcus Lynch had leased the land to the east of Barna Woods to

Galway Golf Club – of which Lord Killanin was President and Colonel Courtney,

Captain – to establish their second home. The need for this arose when Sebastian

Nolan had evicted the Club from the original course that Nolan and Lt. Col

H.F.N. Jourdain of the Connaught Rangers had designed and built on Blake’s

(Gentian) Hill. 12 Nolan had bought the Blake’s Hill headland from

the Alliance Assurance Company of London in 1895 for about £680 (€99,176). The

Allied Assurance Company had been established in 1824 by Nathan Mayer

Rothschild, the English banking scion of the Rothschild family and had come to

control the mortgages on large amounts of land in Connaught.

The land required for the projected east pier of Barna Transatlantic Port

off Blake’s Hill would have required acquiring Sebastian Nolan’s former lands

from the Church. Nolan had died playing golf on the Hill in April 1907 and

probate of his estate of £40,469 12s (€5,405,400) was granted to the Most Rev

John Heally, the Archbishop of Tuam. No doubt the presence of the Bishop of

Galway on the Transatlantic Port Committee would have smoothed the “reasonable”

sale of the required lands. Worthington, and perhaps Marcus Lynch in the

background, seemed to have thought of every eventuality in their detailed

planning.

Despite his family’s history and previous wealth Lynch appeared to be in

serious economic straits by 1910 and would have welcomed the opportunity to

extract himself with the sale of his land to the proposed Transatlantic Port. However,

as with all other Galway Outer Harbour efforts over the previous 60 years the

Barna Transatlantic Port was not to be and by the time Lynch died in November

1916 the scheme had been completely shelved. Marcus Lynch left probate of his surprisingly

small estate of £2,048 16s 0d (€175,420) to his sister Margaret.

Robert Worthington was also left a good deal poorer by his involvement

but this did not deter him from marrying three times and fathering eight

children. He died in 1922 at the age of 80.

THE DREAM CONTINUES

Proposed Galway Port 2015

The 180 year-old dreams of a Transatlantic Port for Galway have not gone

away. 13 I have no doubt that any day soon Fr Peter Daly and Robert

Worthington in Rip Van-Winkle mode will arise and meet each other’s ghost! In

order to service the increasingly lucrative ocean liner tourism a plan has been

put in place by the Harbour Board and now all efforts are being made to get

national and European funding to get the project started. Interestingly as it

has been for nearly 700 years this aspiration has pitted mercantile Limerick

against Galway again, with Limerick vying for the same funds to develop an

ocean liner port at Foynes on the Shannon estuary.

Galway Inner Dock 2016

REFERENCES:

1.Lunde

P. Pillars of Hercules. 1992 Aramco World 43, 3

2.Woodman

K. ‘safe and commodious’ – The Annals of the Galway Harbour Commissioners

1830-1991, 2000, Galway Harbour Company

3.Hurley

MJ The Galway Train 2016 Lackagh Museum & Community Development

Association. Smashwords.com

4.Ó

Gráda C, O’Rourke KH Migration as disaster Relief: lessons from the Great Irish

Famine. 1997 European Review of Economic History, 1 (1): 3-25

5.Collins

T. Transatlantic Triumph and Heroic Failure: The Galway Line 2003 Collins

Press, Cork.

6.Hardiman

T. History of the Town and County of the Town of Galway. 1820 Folds & Sons,

Dublin, p.60

7.British

Parliamentary Papers HC1859 (257) Session I XVII

8.Report

to Admiralty by Capt. Washington R.N., Captain Vetch R.E. and Mr Barry Gibbons

C.E., on the Capabilities and Requirements of the Port and Harbour of Galway.

House of Commons. 2nd March 1859

9.Kelly

RJ. Galway as a Transatlantic Port. 1903 Pamphlet, McDougall & Brown,

Galway. p 24

10.Ocean

Mail Services, (Additional Papers), Houses of the General Assembly, Session II,

1912, New Zealand; Papers 256 & 257, p. 76

11.Worthington

RS, Galway as a Transatlantic Port, 1913 The Railway Times, p.80

12.Derham

RJ. Galway – Guano, Golf, and Gethsemane: June 26, 2015 Available at: http://deworde.blogspot.ie/2015/06/guano-golf-and-gethsemane-in-galway.html

13.http://www.galwayharbour.com/new_port/