Battle of Maniaki May 20, 1825

Rihla

(The Journey) – was the short title of a 14th

Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar Ibn Jazayy

al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue

of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels

of Travelling and somehow the title of Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos

of many of the city and country journeys I have been lucky to take in past

years.

Some of the most

interesting journeys you can take are those that are accidental, unplanned,

happenstance almost; where the outcome, because of a decision to undertake that journey then becomes not so much a revelation but “enlightening”. This Rihla is about “METAMORPHOSIS”, the transfiguration of an individual and place in the course and cause of revolution.

METAMORPHOSIS

I found myself sitting, happenstance, on a hot late June day, out of the heat, in the

small covered portico of the ancient Church of the Metamorphosis (Μεταμωρψδη – Transfiguration)

on the road between Chora (Χωρα) and Messini in the SW Peloponnese. Why stop here, I wondered. I had

intended visiting the Mycenaean Nestor’s Palace ruins as well as the museum in

Chora, but forgot it was a Monday and that the archaeological attractions were

closed for the day. It is wonderful, I thought while biting into a

succulent peach, when travelling or exploring to lose track not just of time but of entire

days. Given my surroundings I should have perhaps switched to the modified post-Byzantine Revised Julian calendar of the Orthodox Church rather than its Roman Gregorian replacement. Perhaps I could have metamorphosed the day of the week!

Where

to next, I wondered aloud?

Church of Metamorphosis,

Metamorphosis, Messenia, Greece

The old church was very basic in its construct, a very “still” place,

and almost certainly an early physical manifestation of hesychastic Eastern

Orthodox doctrine. The Metamorphosis or Transfiguration of Christ as depicted

in the Gospels is a major component of Eastern Orthodoxy, one of the twelve

feasts. Indeed there is a suggestion that in contrast to the Roman Catholic

church’s primary theological ceremonial emphasis, that marking the death and

resurrection of Jesus Christ, the Eastern Orthodox church’s most important

theological celebration, is now that of Jesus Christ’s (mankind’s) encounter

(transfiguration) with the Divine Light on Mt. Thabor. It is a theological contrast between

a theology of fear and a theology of enlightenment.

Transfiguration mosaic from

St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai.

Choosing enlightenment I took out my Anavasi 1:80,000 topographical map

of Messinia to scan the road ahead. Not far away was the village of Maniaki and

slightly beyond it there was depicted on the map a Church dedicated to the Holy

Trinity at a place called Tampouria. My translator said that this was the word

for a military "breastwork" or redoubt. On the map there was an associated legend of a small

Greek flag but the Legends section of the map did not detail what these small

Greek flags indicated. I suspected, but was not certain, they indicated a site associated with heroes

or events of the Greek Wars of Independence. There were similar flags on the

village of Nedoussa (where Nikitaras Stamatelopoulos, the “Turk-eater” was

born) to the east in the foothills of the Taygetus mountains – which I had passed close

to a few days previously on my way to Mystras – and also further north in Ano Psari and Pamoboyni.

I left the old Church of the Metamorphosis behind me, turned left at the

Touloupa Chani junction and winded my way up the road to Maniaki. On that stretch

I passed a observation post for the rural fire service with an attendant fire

tender parked ready on standby. From that spur of the Egaleo mountains the

firemen could survey the entire territory southwards towards Kalamata to the

east and Pylos to the west, and thus be able to intervene early in any fire

outbreak.

For a similar reason of good visibility, further up the mountain just

beyond the village of Maniaki, Gregorias Dikaios a.k.a. Papaflessas, Orthodox

priest, revolutionary fighter and Minister for the Interior and Chief of Police

since 1822 in the Provisional Administration of Greece established his redoubt,

built his breastworks, and on the May 20, 1825 met his death confronting the

army of Ibrahim Pasha.

Papaflessas Memorial Tampouria, Messina, Greece

REVOLUTION AND

METAMORPHOSIS

“Of

these agitators the best known and most influential was the Archimandrite

Dikaios, popularly known as Pappa Phlesas, a priest whose morals were a scandal

to the church, as his peculations were to the national cause, yet, for all

that, a brave man, as he proved by his heroic death on the field of battle.”

W. Alison Philips (1897)

The War of Greek

Independence

1821 to 1833

Georgis “Papaflessas” Flessas a.k.a. Gregorius Dikaios was born in 1788

in Poliani village, located about 21km north of Kalamata in the Vromovriseika

Mts. The village was also the birthplace of Christos “Anagnostaras” Koromilas.

His family were descendants of klephts,

mountain outlaws who continuously opposed the Ottoman occupiers of Greece.

Papaflessas Memorial Tampouria, Messina, Greece

Young George Flessas from an early age was determined to root out the

Ottomans and get under their skin. While attending the famous school at

Dimitsana he published a satire against the local Turk governor and had to

quickly “disappear” for his own safety into the monastery at Velandia, where he

decided to become a priest and took the monastic name Gregory Dikaois. Even

there, and also when asked to leave because of his argumentative bent, at his

next port of call in the monastery of Rekitsa he was turbulent, fighting with

his superiors, and with local administrators. Accused of treason he disappeared

to Zakynthos for a time before finally making it to Constantinople, being

ordained into the highest rank of priesthood, and beginning his formal

revolutionary metamorphosis by joining the secret Filiki Eteria organisation that had been established in Odessa in

1814 and run along Freemasonry lines with the leaders calling themselves the

“Invisible Authority”.

Once ordained Papaflessas was dispatched as a “missionary” and spent

1819 and 1820 preaching Greek independence rather than theology in Wallachia. By

January 1821 he was back “home” in the Kalamata area initiating members into

the Filiki Eteria and organising

revolutionary meetings. On

the 23rd March 1821 Papaflessas, Nikitaras, Anagnostaras made their

way from the Monastery of Mardaki to Almyros Kalamata to take delivery of a

landing of military supplies. Although there is some dispute about when and

where the Greek War of Independence (1821-1832) began but March 25, 1821 is the

official date.

church of Holy Trinity, Tampouria, Messinia, Greece

This dispute

over who did what, how much and when they did it, was and is a feature of the Greek War of

Independence's multi-layered historiography. What is not in dispute are the

atrocities, the ethnic cleansing, the indiscriminate rape, torture, and

extermination of men, women and children conducted by both sides, but by the

Greek side in particular during the early phases. This cleansing was conducted with an enormous ferocity and

appetite for vengeance and in many cases unappeased Greek blood-lust was also to be

subsequently directed against themselves. Indeed unlike most countries where a

Civil War between opponents of the “road ahead” usually followed the original

War of Independence, as in the US or in Ireland, the Greek War of Independence from

the Ottoman Porte was characterised by being conducted at the same time as two internal

Greek Civil Wars between 1824-1825.

Navarino Bay from North. The Venetian Paelokastro on top

of headland to right of picture. In distance is Pylos where the Navarino neokastro is.

In middle is Voidokilia Beach and beyond on right Sfaktiria Island.

Despite fighting

alongside the famous freedom fighter Theodoras Kolokotronis at the Greek

victorious battle of Dervenakia in July 1822, Papaflessas, as he was now known

in a nom de guerre, accepted as

Gregorius Dikaios the post of Minister of Internal Affairs and Chief of Police

in the first Provisional Greek independent government. In that position as

Minister of Internal Affairs he had to sanction the capture and imprisonment on

Hydra in February 1825 of his friend and commander Kolokotronis, as a consequence

of Kolokotronis’ civil war opposition to the new administration.

On February 24,

1825 Ibrahim Pasha, the son of the ruler of Egypt and at the request of the

Ottoman Sultan, landed in Modon (Methoni) with 4,000 infantry and 500 cavalry and

a month later was joined by a further 6,000 French trained and battle-hardened Egyptian

infantry, as well as 500 cavalry, to confront and supress the nascent Greek

revolution.

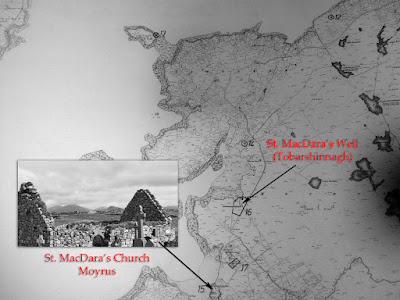

1880's Map

On the 19th

April 1825 an irregular force of 7,000 Greeks and Albanians under Skourti, set

out to try and intercept Ibrahim’s advance as well as trying to relieve the

garrisons in the Neokastro in Pylos and on Sfaktiria but were routed by the

discipline of Ibrahim’s Arabs and forced to retreat. Unimpeded Ibrahim captured

the old Navarino fortress (paleokastro) to the north of Navarino bay on the 29th

April, Sfaktiria island on the 8th May and finally the new Navarino

castle at Pylos on the 11th May. Anagnostaras, Papaflessas

fellow-villager and friend, was killed in the defence of Sfaktiria.

Following these

set-backs and recognising the extreme danger posed by Ibrahim’s campaign to

establishing the new independent Greece Papaflessas pleaded with his colleagues

to release Kolokotronis so that he may command an army to confront Ibrahim

Pasha. The Interim Government refused and Papaflessas stated that he would take

and lead an army himself to make a stand. The Government were more than willing

to allow their truculent Interior Minister to depart. Always the showman Papaflessas marched off to his destiny accompanied by his two mistresses.

Looking North from Tampouria, Greece

Papaflessas

arrived and after discussing with villagers the best place to observe the plains dug into three positions above the village of Maniaki, erecting temporary breastworks on the karst

exposed hills, with about 3,000 troops. He instructed that the Breastworks (Tampouria) be set on the oblique and not the crest of the hills as this made them easier to defend. One of the three main positions was commanded by his nephew and he was expecting his brother to join him with about 700 more infantry. During the night of the 19th

May 1825, the night before the Battle of Maniaki, about 2,000 of the Greeks

melted away when they perceived the size of Ibrahim’s force camped in the

valley below them. The following morning one column under Ibrahim Pasha's French commander took the easterly approach and Ibrahim pasha the westerly, splitting his own detachment in two to meet up again for the final assault on Papaflessas' position.

Papaflessas vowed to die where he stood in defence of

Greek independence. His wish for martyrdom was granted and he and 600 of his

troops lost their lives, including his nephew, an Italian volunteer and his flag-carrier.

Some reports state that Ibrahim Pasha kissed the head (decapitated)

of Papaflessas in honour.

Following the battle Ibrahim sought out his headless

body and head of his adversary and set these upright up on a post once the body

parts had been cleaned. This was an act of honouring his opponent and he is reported

to have said, concerning Papaflessas,

“That was a brave and honourable man! Better have

spent twice as many lives to save his; he would have served us well.”

Unlikely! Pappaflessas would have continued in whatever guise to be a “turbulent” priest. Papaflessas

metamorphosis, a bit like that of Henry VIII’s Beckett, from truculent priest

to martyrdom had been achieved and today is marked, is remembered, by a blue

Greek flag, a collective memory, on a map and on the ground.

TAMPOURIA

The actual

Battle of Maniaki took place about 4 km north of Maniaki on a small hill now

known as Tampouria. Tampouria derives from Ταμποúρια a Greek word that defines

a temporary or hastily erected Military fortification known as a breastwork or

sconce. A signpost indicating its position, is nestled in a grove of tall

Cypresses, about 2km beyond the turn-off for the village of Maniaki. There is a

short winding road to an open parking area and then perhaps the most

beautifully constructed external stairway I encountered in Greece.

Icons and Imperial Byzantine Eagle on Candle Box.

The official flag of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul, which

represents the Orthodox community worldwide

is a double-headed eagle holding an orb and a cross. In this church the eagle

is holding two orbs, while outside fluttering in the wind is the more recently

adopted, and a more belligerent flag, with the eagles holding an orb and a sword,

rather than a cross. (The double-headed eagle was originally a Hittite 14C BCE motif and was adopted by the Byzantine Palaiologan dynsaty when they wrested back control of

Byzantium from the Latins in 1250s)

After a short

climb you encounter the 1975 refurbished Church of the Holy Trinity. Through a

window can be seen the icons as well as the Byzantine imperial flag adopted by

many Greek orthodox churches. Outside the Greek flag on its pole flutters in

the late afternoon wind, and as well as an obelisk, there is upright stone

engraved memorial slab to the fallen as well as a black stone sculpture of

Papaflessas.

To the east and

below behind the sculpture are the alonia (drying floors) of the joint villages

of Ano and Kato Papaflessas, formerly known as Kondogoni, but renamed in his perpetual honour. Bones from the battle were gathered and are in an ossuary in the Church of the Resurrection on an outcrop east of Maniaki village.

Tampouria I found to be a strange place. In the middle of an ancient landscape well used to glorious death many Greeks considered Maniaki to be a 19th century Thermopylae, and Papaflessas to be Leonides. A natural rampart which for a brief moment in time held the hopes of a nation, and of its defenders within its hastily erected stone redoubts... and then let them go.

Papaflessas

For Papaflessas perhaps Tampouria was his Mt. Tabor. The statue depicts a proud, defiant man and is a sculpture that engages your eye, framed by the sky and the rocks, of the place

where he lost his life defending his ideals of Greece, of a place where perhaps he finally found enlightenment...and was at peace.