MacDara's Island

©www.jimfitzpatrick.com

Rihla (The Journey) – was the

short title of a 14th Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic

legal scholar Ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed

the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title

was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the

Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling and somehow the title of

Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos of many of the city and country journeys I

have been lucky to take in past years.

Some of the best journeys you can take are those

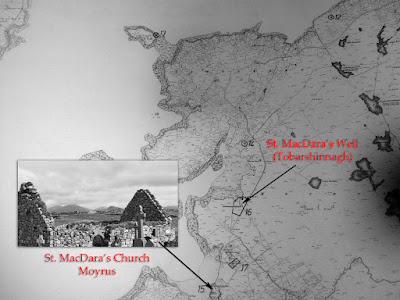

closest to you. This Rihla is about the island hermitage of St Sionnach MacDara

(on the island od Cruach na Cara a.k.a. Cruach Mhic Dara or Oileán Mhic Dara),

the patron saint of Connemara fishermen, that is located off the south-west

coast of Connemara near Mace Head and the annual fishermen’s pilgrimage to the

island held on the 16th July every year.

Little is known about the

life of St. Sionnach MacDara and yet he is venerated in a very significant way

on Iorras Aithneach (Iar Ros Ainbthech – Western Promontory

of the Storms), the Carna Peninsula in south Connemara. His ecclesiastical

feast day is listed in O’Hanlon’s Lives of the Irish Saints as being on

September 28 and yet Connemara fishermen also perform an intensely secular patrún or pattern in his honour on their

turas or pilgrimage to the island on

the 16th July every year, weather permitting. In addition to the Oratory church on the island there is a church dedicated to him in Moyrus and also a Holy Well.

Not bad for an almost

unknown saint.

Tradition associated with St Mac Dara meant that any fishing boat passing through the sound between Masson Island and MacDara had to lower their sails three times (modern boats with outboard motors still cut their motors in respect of the tradition) otherwise bad luck would hit them.

His given or forename Sionnach means fox, but Tim Robinson in his

book, Connemara – A Little Gaelic Kingdom feels it should be Síonach which means a storm or stormy

weather, and very appropriate as MacDara is one of the two saints associated with the Iorras Aithneach (of the storms) peninsula.

What is most likely is

that Sionnach MacDara was a monk or cenobite

in one of the early or mid-6th century St Enda’s, St Brecan’s or St Ciaran’s

monasteries on Inishmore of the Aran islands. St Enda is considered the father

of Irish monasticism and his foundations followed the asceticism of the

Egyptian “desert Fathers”, living in community but with a life dictated by

manual labour, study and prayer. St Ciarán Mac an tSaeir (of Clonmacnoise fame)

is the other major saint associated with the Conmaicne Mara tribal area of

Ioras Aithneach and perhaps this points to MacDara being a cenobite in his

Inishmore monastery and they may have left the Aran islands around the same time, circa

541 CE, with MacDara heading to establish his “hermitage” island off Mace Head and Ciarán

joining Senan on Scattery Island at the mouth of the Shannon before moving inland and founding Clonmacnoise.

Landing at Aill na hIomlachta

(The Rock of the Ferrying)

Looking East South East

The 6th century

saw the rise of the Irish “island hermit” tradition, such as that seen separate

to the main complex on Skellig Michael (see Rihla 63) on the south peak; on Church Island near

Valentia, Co Kerry; on Inismurray in Co. Sligo; or on High Island off NW Connemara

where cenobites wanting to remove themselves from the community moved to almost

inaccessible islands to become “Green Martyrs” (as distinct from Red Martyrs

who were killed for the “cause” – very few instances in early Christian or

pre-Viking 9th C Ireland) . The difficulty is often that these type

of ascetic hermits then attract a community to themselves hoping to

partake in the holiness and this is what appears to have happened on St

MacDara’s Island.

The oratory, which is a

corbelled stone roofed rectangular church was beautifully restored by the OPW

in the 1970’s, a restoration first mooted by R.A. Macalister in a paper

presented to the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland in 1895, following his

visit to the island, “A very little outlay would put the whole structure in

sound state, and doubtless, preserve it for another 1200 years.”

Of note Macalister in his

visit, found lying face down one of the carved finials that previously had been attached to the apex of the east

gable end. The native fishermen of the 1800s considered the carved head in the

centre of the stone to be that of St. MacDara himself. This finial (and

presumably the other at the western end) subsequently went missing and was

nowhere to be found when the OPW went about restoring the Oratory. There is

some difficulty in accurately dating the church with some authorities believing

that originally the roof was a wooden construct and that sometime later,

perhaps after the main Viking incursions had settled down, the roof was remade

of more weather resistant (and available) stone. What is important is that

“mouse-ear” carved finials were a feature of early Christian monastic

gable-ends as depicted in the Temptation of Christ in the late 8th C

Book of Kells.

The carved finials as depicted in the Book of Kells. Finials are decorative carvings or pediments placed at the apex of towers (like a cross on a church bell tower or a crescent moon on a mosque minaret), or on the gable end apexes.

The carved gable-end

finials were also a feature of some early “chapel-like” reliquaries such as the

Monymusk casket of St Columba and indeed the gable struts of early 3rd or 4th century BCE Germanic North Sea wooden longhouses may have influenced the design as well as being the direct forerunner of the wooden gable-end cross-beamed curved apexes of the Scandinavian longhouses. What is not in dispute is that the replacement

finials commissioned by the OPW are very fine carvings and are weathering very well.

I went to the island on

the 16th July this year, landing with the first boat of the day. The

festival is now called Féile Mhic Dara and this year I reckoned about 1200-1500

people made it to the island and with the marketing of the Wild Atlantic Way

being such a success the numbers are only going to get bigger and I suspect

that at some point the traditional and “good-humoured” free ferrying of

pilgrims to the island by local fishermen (remember to bring your own, or borrowed,

lifejacket flotation device – not mandatory but important) will come under

pressure.

Unfortunately I was on

call and had to head back to the mainland just before the mass began and I was

unable to observer how many people still might have maintained the ancient

tradition of a seven times circumambulation of the chapel and the placing of

seven pebbles on the altar. I had hoped to see this done, and perhaps ask a

participant why he or she still did it. As a custom it would echo the penitent tawaf circumambulation of the Kaba in

Mecca, (and perhaps also the Stoning of the Devil) and be an echo of the

Middle-Eastern tradition of Early Christian monastic communities that gave rise

to the stylites of Syria and the island hermits of the west coast of Ireland such

as Sionnach MacDara.

Even

without this oblique association between the patrúns of East and West I found the geography, the historical

context, the convergence of the Galway Bay hookers at the small harbour, the

gathering of fishermen’s families from all over Connemara speaking Irish, the

gathering of the sky and sea on an ancient landscape, the acceptance of tourist

pilgrims, and finally the architecture of the conversation between mankind and

God absolutely fascinating, all of them speaking to a distant time and place…

in the now.