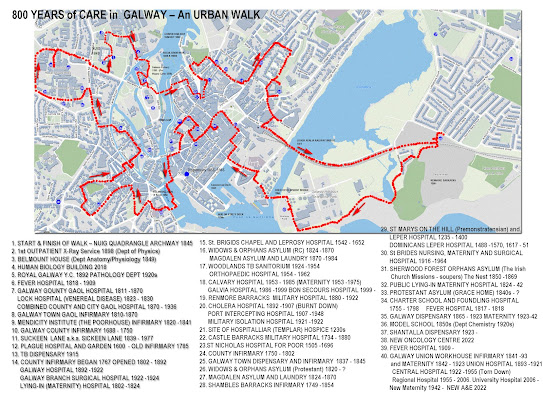

This particular Rihla is entirely local to the place where I live. It is an account of an urban walk I organise on the last Sunday of most months, wandering through time and location in Galway to touch upon – to imagine in many instances – the appearance and disappearance of a town’s history of social care/health institutions. It is and will always remain a work and a walk in progress; evolving as new buildings are erected, new care functions established for the future and more information about the past becomes available.

INTRODUCTION – CARE AND PLACES OF CARE

“If anyone batters a man so that he falls ill, he (the assailant) shall take care of him. He shall give a man in his stead who can look after his (the victim) house until he recovers. When he recovers, he shall give him 6 shekels of silver, and he shall also pay the physician's fee.”

Hittite Legal Text cuneiform c. 1500 BCE

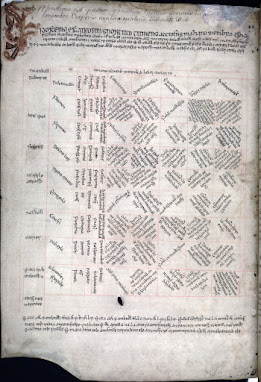

In quoting this translation of a Hittite legal tract Calvert Watkins agreed with D.A. Binchy’s 1938 determination of an almost exact similar – albeit much later – “sick-maintenance” wergild provision in the 5/6th Century Irish Brehonic “folog northrusa” or “orthrus” laws. Binchy surmised that when the main source of our knowledge in regard to Irish early-medieval sick-maintenance, the Breatha Cróilge law tract concerning health-care is analysed, it reflects the incorporation of an Indo-European tradition stretching back almost 2500 years.

What is not very obvious from either Hittite, or the later Brehon laws, is how much “sick-maintenance” took place in stand alone institutions (hospitals or infirmaries as we might recognise them) in contrast to the more general delivery of care in the victim’s own home or sometimes that of an assailant.

According to legend in an Irish context, the first institution that might be recognised today as a hospital was founded in the 4th century BCE (Before Common Era) by Queen Macha Mong Ruadh (died 377BCE). It was known as a Broin Bherg (the House of Sorrow) and situated at Emain Macha or Navan, Co. Meath and like the later military-only valetudinaria of the Roman Legions, was dedicated to the care of Red Branch knights.

Prior to this establishment of a physical building or location, again in Irish historic tradition, the great mythical physician was the Tuatha De Danaan god of healing known as Dian Cécht who along with his three of his children, his sons Octriuil (liaig) and Miach and daughter Airmead (banliaig), tended the soldiers of the Red Branch Knights while still on the field of battle.

From an earlier epoch, c.3500BCE, it appears from clay tablet analysis that Mesopotamian “asu” or therapeutic physicians maintained small “recovery” units/clinics/rooms but generally delivered treatment, according to the later more formalised c. 1700BCE Hammurabi code, in patients homes.

In general, and in common with the practices on mainland Europe, Irish traditional medicine and healing was also done in the patient's own home but with a few nuances. By the 5th century in tribal Ireland the more established ‘tuatha’ or petty kingdoms had designated “foras túaithe” or secular places of “rest” or “recuperation” for wounded/injured/infirm people of that tuath. These were erected in close proximity to the óenach or headquarters site of the clan. The dominant and larger clans would also have had hereditary physician families living in the óenach. Throughout the country there were also more primitive and generally isolated "teach allais" wattle and hide sweat-houses or sauna-like places of healing, a tradition that persisted into early 19th century.

The Irish tribal tradition of the major hereditary medical families such as the Ó hÍceadha (Hickey) – from the Gaelic for healer – attached to the O'Briens of Thomand and the Uí Laidhe (O'Lees) attached to the O'Flaherties of Iar Connacht usually implied a specific grant of land, within the tuath, where the medical family would establish their home, a herbal garden, a place to see patients and also on occasions to establish a medical school such as the early 6th century St Bricín's monastic medical college at Tuaim Dreagain (Tomregan, Co. Cavan) and the later, famous early 16th century O'Connor medical school at Aghmacart, Co. Laois.

It is unknown whether the Clan Fergail, the O’Halloran tribal family in whose tuath Galway city is situated had such a foras túaithe but if they did it would have been located on the current site of Barna House on Rusheen Bay where the O’Halloran castle and clan óenach was located.

(see: http://deworde.blogspot.com/2016/10/rihla-journey-61-hall-of-red-earl.html)

HOSPITAL CARE DELIVERY DEVELOPMENT

The first reasonably well-documented institution that we might recognise as a functioning hospital was the Ayurvedan medicine teaching hospital in Taxila in Northern Pakistan, which existed from 500BCE. About 200 years later Buddhist monastic health care sites with stand-alone defined hospital structures were beginning to be established, most notably at Anuradhapura, Madirigivi and Polonnaruva in Sri Lanka. Gautama Buddha lived c. 563 - 483BCE. From Sinhala (Sri Lanka) the monastic-hospital template spread with Buddhist missionaries as far as Japan by 552CE (Common Era).

The Buddhist notion of hospitals being established co-existent with monastic settlement to deliver healthcare was also to later transfer, almost intact in mission, to the early Christian hospital complex established in 369CE by St. Basil in Basilica (with specific wards for different diseases including wards for leprosy where sufferers were treated inclusive for first time as well as a hospice for travellers and an industrial school) just outside the town of Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia, Turkey.

The actual occidental as distinct from oriental Buddhist architecture of the new Basileias institutions may have been influenced by the layout of the famous dormitories of the c. 350BCE Greek Asclepieia, but more likely by the c. 100BCE ( the first at Carnumtun near present day Vienna) development and function of Roman Military hospitals known as Valetudinaria (“get well places”), but this conclusion is uncertain.

The Basilica template was to establish subsequently very rapidly right throughout Byzantium Greek Orthodox lands where hospitals were to become known as xenodochion and then later in Latin Roman Catholic western lands where they were known as hospitalium. The Benedictine order, founded in 529CE in Montecassino by St. Benedict of Nurisia became the most influential health care delivery monastic order in the west and by 8ooCE Charlemagne had mandated that a school, a monastery and a hospital had to be attached to every new cathedral built in his territory.

To the east the development of bimaristan hospitals in Persia, beginning with Gundeshapur’s hospital in South Western Iran in 500CE was heavily influenced by Nestorian physicians, a tradition which was then continued in the development of the great Abbasid Islamic hospitals, first in Baghdad and then beyond.

This monastic associated tradition of health-care delivery in Ireland was to last until the suppression of the monasteries by Henry VIII between 1536 and 1541. Following this there was a devastating lacunae and a greater dependence on secular places of healthcare delivery, which were very haphazard in their establishment and ambition and quality of delivery, relying usually on a small pool of wealthy merchants and land-owners (the Grand Juries) to fund and run the institutions.

As James P. Murray has pointed out in his seminal study, Galway: A Medico Social History, the notion of “hospital” or “spital” was used in medieval and post-medieval times to include almshouses or poorhouses where the poor and infirm were cared for, primarily by putting a roof over their heads and providing sustenance.

In Galway the post-1540 secular, and oftentimes sectarian, healthcare delivery began to change during the 1850s when increasing Catholic emancipation and advocacy, and the devastation wrought by the Irish Famine, allowed the development and funding of more formalised pluralist healthcare again both within and from defined architectural "healing" spaces such as those that had been enabled by the Poorhouse and County Infirmaries Acts of late 18th century.

LOCATION 1

ARCHWAY OF NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND GALWAY (NUIG) QUADRANGLE

In 1845 Queen’s College Galway was established – along with sister Colleges in Belfast and Cork – after beating off the rival claims of Limerick. The College, despite very serious difficulties with the contractor and the suicide of the contractor’s agent, was built in the very short space of time of 4 years and was opened for students in October 1849.

The proposal to establish a secular institution detached from formal religious control by Peel’s government administration in Dublin Castle managed to unite most main “Christian faiths” and some politicians in their opposition to the intent (and danger perhaps) of a non-denominational University educational ethos, an ethos and intent which was already being put in place in the new national primary education system – the first Model School opened in 1834.

The Colleges, called by Daniel O’Connell – in an act of political expediency to retain the support of the Catholic hierarchy in his Repeal activities – “Godless academies” and by the Protestant Sir Robert Inglis “a gigantic scheme of Godless education” were, while construction was taking place, being formally condemned by the Pope in 1847 and 1848. The Catholic Archbishop – and future Cardinal – Cullen at the Synod of Thurles in 1850 paraphrased the politicians when he said to the assembled prelates, when referring to the new Colleges, that, “One alarming spectacle of the present times, is the propagation of error through a Godless system of education.” This opposition over next 60 years was hasten the end of the non-denominational Model School national primary school system but not the new Colleges.

The final decision on the location of new Queen's College was left to Kirwan, the first president of the College. Belmount House on about 8 acres was bought from John Whaley of Dublin and further fields on its eastern boundary from Lachlan MacLachlan, owner of the Linen factory, giving a total area of 14 ½ acres at a total cost of £3,469-9-0, about €500,000 in current value. The reason the land was so expensive (in contrast to Nuns Island purchase for the new Gaols) was that no compulsory purchase facility was incorporated in the legislation enacting the building of the College.

John Whaley was the inheritor of the estates granted under the 1653 Adventurers Act to Henry Whaley, Recorder of Galway, a cousin of Oliver Cromwell, and brother of Edward Whaley one of the “Regicide” judges at trial of Charles I. His son, also a John Whaley inherited and when he died he left his Galway town lands to Susannah his daughter. She married a cousin Richard Whaley and their Grandson was the famous Buck Whaley.

Like MacLachlan John Whaley died shortly after selling his lands for the site of new College and before seeing the college buildings completed.

(For more information on the Whaley connection and development of Newcastle area of Galway see:

http://deworde.blogspot.com/2018/04/rihla-journey-66-newcastle-to-salthill.html )

From early on the Medical School of the new College was dynamic and 82 of the total of 427 students enrolling in the new College between 1849 and 1859 studied medicine and by 1882 medical students were accounting for 50% of each year’s enrolments. This was remarkable given difficulties with clinical attachments. Students were only able to partially access surgical and medical patients in the County Infirmary and Workhouse Infirmary and formalised access to maternity patients was not possible until 1923 when a new maternity hospital was established. In truth most students did their required 24 months clinical attachments in institutions recognised by the College senate away from Galway. Charles Croker-King was the Foundation Professor of Anatomy and Physiology.

LOCATION 2

DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS, SOUTH WING, QUEEN’S COLLEGE QUADRANGLE - 1st OUT-PATIENT X-RAY DEPARTMENT

In 1898 in the Queens College Quadrangle on the South side, lower floor mid-section, the Department of Physics installed one of the first ever available x-ray machines. Patients came here as outpatients to be “x-rayed”. This was only 3 years after the German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen had freely disseminated his discovery of x-rays and 2 years after Thomas Edison developed an x-ray imaging device, a fluoroscope which used calcium tungstate as a screen and was known as the “Vitascope”.

The 1898 equipment in Galway's Queen's College may have been “jerry built”, using locally blown Crooke’s Tubes and high-voltage generators and based on Roentgen's and Edison’s publications, but also could have used commercially available equipment from the Edison General Electric Company “miniature lamp” subsidiary. Roentgen had deliberately refused to patent his discovery of x-rays. The "x-ray" machines, in order to produce the x-rays, required a high voltage electrical source and this was only possible because 8 years earlier Galway had been partially begun to be “electrified” around 1890 by the Galway Electrical Company [founded 1888] AC hydroelectric turbine and generator installed in Newtownsmith by James Perry, the Galway County Surveyor, and also the father of Alice Perry, the first female first-class honours engineering graduate in Ireland and the UK.

In 1902, 7 years after discovery of "x-rays", a child received radiation burns to his knee following a series of x-rays in the Physics Department and the parents sued the College for negligence. Despite the resulting court case in 1904 making no finding of negligence the College decided to have the machine transferred to the Galway Hospital on Prospect Hill, although the Physics Dept. technician, a Mr William Hare, continued to operate the equipment on a fee per item basis. When the Galway Hospital transferred to Central Hospital in Newcastle 1922 new commercially available equipment was bought for £17.

Of note in 1904 Thomas Edison also abandoned his work with x-rays after the death from radiation induced hand burns and mediastinal cancer of his laboratory assistant Clarence Dalley.

LOCATION 3

BELMOUNT HOUSE - DEPARTMENT OF ANATOMY

This was the original late 18th century Whaley (sometimes spelt Whalley) Estate house and housed the Department of Anatomy from 1852 – 2018. The foreman supervising the building of the Queen's College lived in Belmount until the works were completed and then the Anatomy and Physiology Department moved in. The building underwent modifications in 1911 and again in 1952. It has one very unusual feature in the old Anatomy semi-circular, steeply banked teaching lecture room where there is a trap-door in the floor through which the cadavers for dissection demonstration ascended from the crypts below.

Belmount is now part of the centre for Medical Simulation Teaching and it is where I, although retired from clinical practice, continue to teach part-time 4th year medical students in obstetrics and gynaecology. The Medical School of the National University of Ireland Galway currently graduates about 190 students in medicine per year, from over 40 countries. There is a current proposal to apply for funds totalling €40 million to build a new Medical School (for 3, 4 & 5th year clinical students) on the site of Belmount House. It is my earnest hope that the old Anatomy lecture theatre will be preserved within that development.

LOCATION 4

HUMAN BIOLOGY BUILDING "The Aesclepeion"

This Scott Tallon Walker Architects ( a firm founded in 1938 by Michael Scott which made its initial reputation designing hospitals – Tullamore, Portlaoise etc) designed building cost €34 million opened in 2018 and now houses the Anatomy department as well all of the other human biological disciplines and research units that serve to lay the foundations in the pre-clinical training of the next generation of doctors and nurses who will deliver the healthcare needs of our community and others beyond. The buildings in this part of the campus are built on the grounds of the former Linen Factory, whose repurposed buildings including the Aras na Mac Léinn and the O’Donoghue Performance lie just in front, to the south, of the Human Biology Building site.

LOCATION 5.

NUIG HUSTON SCHOOL OF FILM AND DIGITAL MEDIA BUILDING

ROYAL GALWAY YACHT CLUB 1882 - 1941 (Wooden Building to approx 1930) sold to UCG.

DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY AND BACTERIOLOGY SERVING CENTRAL HOSPITAL 1941 – 1958 until their move to site in Regional Hospital.

LOCATION 6

THE FEVER HOSPITAL

The Fever Hospital was built and run by subscription following Act of Parliament in 1818. There was planning for 40-60 patients spread over 4 wards.

In 1822 a typhus epidemic occurred. Epidemic typhus is a louse-borne disease associated with overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions and caused by the Rickettsia prowazekii bacteria. Symptoms begin about two weeks after exposure with fever and chills and a widespread rash that spares the face. Left untreated encephalitis, delirium, coma and death occurs.

During the 1822 epidemic in Galway there were on average 90 new cases a day at peak. Capacity of the hospital was increased to 120. Temporary wooden shed and tents erected in grounds and an empty barracks on Lombard St was converted into a temporary convalescent Hospital with an extra 100 beds.

Dr McHugh, the medical officer in charge of Fever Hospital died from the disease caught tending the patients as also did Drs Keogh, Brown and Burke in 1823, all of whom had come to the assistance of Galway in dealing with the epidemic with the Dr Graves commission dispatched from Dublin.

In the two years 1839-40, (quiet years when there was neither famine or epidemic!) there were 3,138 admissions and 223 deaths. Head nurse was a Nurse Barnacle, whose husband was a Stephen Barnacle and whose relationship to the more famous Nora is unknown.

In April 1849 the Fever Hospital was converted to a specific Cholera Hospital. The cholera pandemic had reached Ireland in December 1848 just as the worst ravages of the Famine were receding somewhat. The pandemic lasted about 6 weeks and was responsible for about 600 deaths in the town. The mortality of the 500 or so patients admitted to the Cholera Hospital was about 50%. The cholera hospital reverted to again being a fever hospital on the 1st June 1849.

The Fever Hospital closed in 1909, and was bought by the University in 1913 and converted into the University Men’s Club. It is now the NUIG Irish Centre for Human Rights and the place where I studied for my Masters in Human Rights Law.

LOCATIONs 7 & 8

GALWAY TOWN AND COUNTY GAOL HOSPITALS

The "LOCK" HOSPITAL

The building of a Galway County Gaol was enabled by an Act of Parliament in 1802. A compulsory purchase order of the Nun's Island lands bought them for £664.7.6 (€83, 789.00 in todays money). The construction of both County and City Gaols was completed in 1811.

Both Gaols contained a hospital, the County Gaol hospital being much bigger. Because some 16% of arraigned female Gaol inmates were prostitutes and that the majority of these suffered from venereal disease, their management in the County Gaol Hospital resulted in the Hospital as early as 1823 being considered a "Lock" Hospital (Venereal disease) by the Prison Inspectorate.

Following the introduction of the Contagious Diseases Acts 1864-1886 (primarily designed to protect the military!) women merely suspected of being prostitutes by a policeman could be brought before a magistrate and forced to undergo an examination. If found to have gonorrhoea or syphilis they then could be detained in a Lock Hospital (e.g. Kildare or Limerick Lock Hospitals) or a Lock Hospital situated within a County prison for up to 9 months.

There were always difficulties in the two Gaols of co-housing women who were ordinary criminals and those who were “corrupting” prostitutes. By 1884 the 24 cells of the Town Gaol became exclusively a female prison. The last female prisoner in Galway Gaol was Delia, a 40 year-old waitress of no fixed abode, who was convicted of malicious damage to church property, and died in the gaol hospital 4 days after being remanded.

The County Courthouse built 1815 and Town Courthouse in 1818. The Gaol bridge (now known as Salmon Weir bridge) from the Courthouses to the Gaols was built 1818-19.

Public executions outlawed in 1868. After that took place in prison yard. Last execution in Galway gaol was 1902 on a temporary scaffold.

Both Gaols closed in 1939 and were demolished (apart from wall) in 1949. Site sold to Bishop Browne for £10. Cathedral of Our Lady and St Nicholas built 1965. On a personal connection my father Joe Derham was the electrical and mechanical engineering consultant to the Cathedral construction.

8.A: GALWAY TOWN HALL INTERNMENT CAMP 1920 -21

Linking the Galway Gaols to the Galway Courthouses (County Hall & Courthouse 1815; Town Courthouse and later Town Hall 1818) was the New, Goal or Salmon Weir bridge completed about 1819. Both the County and City Halls had been built on what is/was St Stephen's Island. A prisoner sorting station or internment camp was established in the Galway City Hall during the War of Independence and housed up to 100 prisoners in filthy unsanitary conditions. On the 1st January 1921 a Patrick Walsh from Hollymount, Co. Mayo died from fever.

On the 3rd January another prisoner, a Galway county footballer called Michael Mullin from Mountbellew, died three days later after being transferred to the old Cholera/ Isolation Hospital at Rinmore Point. He was diagnosed and treated in the Town Hall by a Dr Thomas Heneghan from Ballindine, Co.Mayo who was also a prisoner and who subsequently was allowed accompany him to the Isolation Hospital.

Many prisoners were "screened" and tortured either in Galway's Eglinton Barracks by the Black & Tans (British reinforcements of the Royal Irish Constabulary [RIC] with a penchant for torture and violence) or the Auxillaries (Winston Churchill's suggested "special" squad of ex-British army officers raised as a counter-intelligence unit in the War of Independence and attached as a paramilitary unit to, but not controlled by, the RIC: an early SAS prototype) from Lenaboy Castle before transfer to Galway Gaol and then to the Town Hall Internment camp.

The prisoners who suffered injuries enough to warrant medical care were transferred to the Military prison in Renmore. Two prisoners from Mayo, Mark Fox and Peter Foy were transferred there with pneumonia after arriving to the Town Hall soaking wet, having being thrown some 4-5 hours earlier into the freezing Robe River to try and get them to divulge information on their Republican comrades.

In early 1921 there was a typhoid outbreak, two prisoners died and a mass inoculation of the prisoners was ordered by Army Medical Officers from Curragh Camp, Kildare and isolation and vaccination took place over a three week period. Following this no more cases were reported. The vaccine against Typhoid (Salmonella) had been developed in 1911.

LOCATION 9

THE MENDICITY INSTITUTION (THE POORHOUSE)

THE WAY TO MEND-A-CITY

Of all the trades agoing now,

A begging it’s the worst, Sir,

Tho’ later it seemed in this good town,

To be the very first, Sir.

It throve so well in every street,

With other trades so blended,

That’twas determined at the last,

The city should be mended.

Oh no! Mendicity’s the way to mend-a-city

Oh no! Mendicity’s the way, to mend-a city.

GALWAY WEEKLY ADVERTISER 27 November 1924

The first applicable legislation for the suppression of begging in Ireland was in 1542 with Henry VIII's An Act for Vagabonds (33 H 8. c.15) followed 100 years later by Chalres I's 1635 Act for the Erecting of Houses of Correction and for Punishment of all Rogues, Vagabonds, Sturdy Beggars and other Lewd and Idle Persons (10&11 C.1. c.4). The latter Act even allowed for “moderate’ whipping but did not proceed in operational terms as no financial supports were put in place.

In 1703 an Irish specific act allowed for establishing a ‘workhouse’ in Dublin. Although ‘poverty’ was recognised legally for the first time in the Act the treatment of those poor was linked to maintaining order and control. In 1735 a similar Act established a ‘workhouse’ in Cork. These workhouses also functioned as “foundling hospitals” for abandoned children and the 1703 Dublin workhouse became the Dublin Foundling Hospital. Both Dublin and Cork workhouses were funded by ‘special taxes’ and not by subscription. Galway did not have a “1735” workhouse but a Founding Hospital was established on the site of the Charter School on Mill Street, where the Presentation Convent is now in 1755 (LOCATION 34).

A more extensive George III 1772 Act repealed the earlier Henry VIII and Charles I Acts and divided beggars into two classes: those who were considered ‘deserving’ and those deemed ‘non-deserving’ of societal support. The Act also segregated beggars into those who were able to work and who would be corporally punished (put in stocks) if they resorted or returned to begging and those who were unable to work and thus given a ‘badge’ or permit that allowed them to beg. The Act also allowed for the erection of more “workhouses’ or “Houses of Industry”; nine of which were established by the time of the Poor Law Union workhouses implementation in 1838.

Dublin’s Mendicity Institution (which still exists on Usher’s Island) was established in 1818, and Galway’s Mendicity Society was in place by 1820. Galway’s population in 1831 census was 33,120. The establishment of Mendicity Societies mirrored the charitable Fever Hospital development, and often funded by the same individuals. The Mendicity Institutes generally differed from the earlier Houses of Industry and later Poor Law union workhouses in that the paupers did not reside in the building. However in any one institution 18-30-% of the female inmates were described as being infirm and in full time care. The percentages for men were less. There was also a children’s ward and basic education unit. The abled bodied were put to work.

The vast majority of Societies were chronically underfunded and with the opening of publically funded Poor Law Workhouse in 1840s rapidly hastened their demise and almost overnight any inmates transferred to the newly established local Workhouse. Galway’s Union Workhouse Infirmary on Newcastle Road opened in 1841.

LOCATION 10

GALWAY's OLD COUNTY INFIRMARY 1680s – c.1750

In 1638 the “able but despotic” Lord Deputy of Ireland (1632-1640) Thomas Wentworth (1593 -1641[executed]) determined that a public infirmary should be erected in Galway. Nothing was done however because firstly there were still simmering tensions in Galway where the Sherriff had been fined £1,000 by Wentworth who had insisted on Charles I’s right to distribute lands to colonists in Connaught – based on his inheritance resulting from the 1340’s betrothal and marriage of Elizabeth de Burgh, Countess of Ulster to Lionel, Duke of Clarence, Charles I’s ancestor – and the onset of the devastating Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649 -1653).

Following the closure of both the Plague Hospital (its former site at the end of Suckeen Lane soon being referred to as the “Old Infirmary”) and St. Brigid’s Hospital on Prospect Hill, in the 1670s the Corporation established a basic small secular infirmary on Woodquay. Its exact location is uncertain but thought to be on corner opposite to where Mendicity Institution was located. It is also entirely possible logical that the Mendicity was established in former County (of the Town) Infirmary location but there was, however, about 7o years between the Infirmary moving to its next temporary home on Abbeygate Street and establishment of Mendicity.

LOCATION 11

SICKEEN LANE aka SUCKEEN LANE (St. Brendan’s Avenue)

In the 1651 map of Galway, Suckeen Lane had only houses on one side and led west north-west from Woodquay to Suckeen Bog (and the Headford Road today). In time because it became the main thoroughfare to both the “Old Infirmary [the Plague Hospital] and the "new" 1802 County Infirmary as well as the 1915 TB Dispensary it became known as Sickeen Lane and was documented as such on the early Ordnance Survey Maps. It was officially renamed St. Brendan’s Avenue when a National School of that name was established on the Lane in 1916 (closed early 1960s.)

LOCATION 12

THE PLAGUE HOSPITAL

The dissolution of the monasteries in 1536-1540 by Henry VIII left the populace of Galway virtually without hospital services. In areas where monastic infirmaries had been numerous, the loss was traumatic. One result was that the people had to return to charms, folk medicine and holy wells. There was St. Nicholas' Hospital for the Poor established and endowed by Stephen Lynch fitz-Dominic Dubh in 1505 (Galway mayor 1504–05, 1508-09, 1517-18, 1522-23), most likely but not entirely certain on what is now Buttermilk Lane. The St Nicholas Hospital/Poorhouse was rebuilt in stone in 1637 and lasted until late 1680s.

In addition to the demise of the 1505 St. Nicholas' Hospital for the Poor, following Henry VIII’s suppression of the monastic establishments the Dominican run Leper Hospital (first established in 1222 on the same site by the Premonstratensian canons) in the Claddagh, in particular, was also lost to Galway’s poor. The Corporation, perhaps following the example of the towns that Galway traded with on the continent, then decided to build and fund a specific, secular Plague Hospital to be established outside the city walls around 1629 when Bubonic Plague was brought to Galway by the returning ships of Charles I from Spain. This Plague outbreak originally had started in France in 1623, and was brought from Lombardy to Spain by returning Spanish troops.

On the 1651 Galway Pictorial map the Plague Hospital is shown as a substantial building with well established associated gardens on the outskirts of the walled town on the southern edge of Suckeen Bog.

Plague is caused by Yersinia Pestis, and is generally transmitted by rat fleas ( Xenopsylla cheopis) but also human fleas pulex irritans (80 species of flea can carry it) with a reservoir of infection in many rodents but also cats and other animals (280 mammalian species can serve as carriers) . The classic carrier was the black rat ratus ratus.

Y. pestis has been found in 3,800 year old skeletons but the first well documented pandemic was the so-called Justinian Plague in 540 CE in Byzantine Constantinople (killing about 1/5 population) the first of nearly 18 subsequent major waves of infection outbreaks (most notably the Black Death of 1340s) that also reached Ireland. The rat flea has a narrow high temperature and humidity requirement to survive and the spread to northern European parts was heavily dependent on climate factors in any one year.

There are three major presentations: bubonic and septicaemic which require the flea vector and pneumonic which is a human-to-human droplet infection. Bubonic plague, manifested by buboe swellings on lymph glands closest to site of bite, had a 50 -60% mortality whereas septicaemic and pneumonic presentations had a 95 -100% mortality.

In October 1347 the Plague arrived in Messina, Sicily from Central Asia and from there throughout Europe with up to 25,000,000 deaths or a 1/3 of the population.

In 1649, 20 years after the Plague Hospital was established, another Bubonic Plague outbreak in Galway was brought in by a Spanish Ship ( Andulasia and Baleric islands had another outbreak since 1647) and this outbreak was to kill 3,700 of the city’s 6,000 residents. Mortality at the same time in Spain/Kingdom of Naples was running at 41-70%. It was therefore remarkable that the adult survivors of the town were able to hold out against the Cromwell’s siege of Galway 2 years later, as the last town held by Roman Catholics. Following capture of the town a further devastating “plague” was visited on the inhabitants but this time it was louse-borne typhus introduced by the besieging army from England.

In modern times there were 2 unrelated plague cases in Yosemite National park in 2015 and a case in Mongolia in 2020 from eating infected marmot, a large ground squirrel.

LOCATION 13

THE CENTRAL GALWAY TB DISPENSARY

The Tuberculosis Prevention Act (Ireland) of 1908, inspired by the work of Dr Seamus O’Beirn’s – the Dispensary Doctor in Leeann - campaign in Connemara and Lady Aberdeen’s Womens National Health Association, authorised county councils to establish TB Dispensaries and Sanitoria.

In 1918 a Central TB Dispensary was established on land to the rear of the County Infirmary at the junction of Bóthar Na mBan and Sickeen Lane (St Brendan’s Avenue) meet and it is where Dr McConn managed the service.

Bothar Na mBan in 1842 Ordnance Survey map was originally a small laneway from Sickeen Lane to rear of Infirmary and may have been named after the women who accessed the maternity part of the hospital this way.

In 1922 alone there were 1,680 patient attendances at the dispensary, 9 were detained in the dispensary and the TB nurse made 1,186 home visits. Until 1949 TB was responsible for 40% of young adult deaths. By that time attendances at the TB Dispensary on Bothar Na mBan were 3-4,000 per anum.

Woodlands Sanitorium was opened in 1922. The city TB out-patient dispensary however operated on Bothar na mBan until 1955 when its services were transferred to new County Clinic in Shantalla. It then became the location for the County Library until being pulled down sometime in 1960s.

LOCATION 14

COUNTY INFIRMARY, PROSPECT HILL

1802 – 1892

COUNTY PUBLICK LYING-IN (MATERNITY HOSPITAL)

1802 -1824

GALWAY HOSPITAL

1892 – 1922

GALWAY BRANCH HOSPITAL (SURGICAL CASES) 1922 - 1924

Following passage of “An Act for erecting and establishing publick infirmaries or hospitals in this kingdom” (Counties Infirmaries Act 1766; 5 Geo III,c.20) “state enabled” County Infirmaries were established in the principal county towns throughout Ireland. Some counties had Infirmaries in two locations. The Galway County Infirmary was begun 1767 but did not get ‘established’ fully until 1802. The Infirmary was located on a site that in 1651 had been a Capuchin Monastery and by 1750s a large inn. The Infirmary, run by designated governors, was supported in the main by a cess on tenant farmers (not the owners of the land), tenants who ironically had no direct access to the hospital; and by the proceeds of the famous “Galway Bazaar” on one occasion and by direct patient payments or permits issued to donors.

A County surgeon was appointed, after examination in anatomy and surgery by the County Infirmaries Board, to every Infirmary. The oversight establishment of the 1766 Infirmaries Act pre-dated the establishment of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1784 by 18 years. Surgeon Thomas Wilkins in the Galway Infirmary was deemed exempt from examination because he had served in the British Army.

The appointment of County Physicians to the County Infirmaries, in contrast, was supervised from early on, following an amending Act in 1768, by the King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland (founded 1654).

Rules and Regulations

The rules and regulations, "to be strictly adhered to", make interesting reading:

Rule VII

No patient to be allowed to spit or dirty the walls or floor of the house, as spitting boxes and bed pots are provided for the purpose; and no smoking of pipes allowed on any account in the wards.

Dr Veitch

The Catholic Scottish First Medical Superintendent

The County Hospital traditionally served patients from the County and did not provide meaningful access to patients from the Town of Galway. In addition there were very poor relations between the Infirmary and the Queens College with the superintendent blocking access, forcing most Galway medical students to get their clinical attachments outside Galway. The new Galway Hospital Act of 1892 sidelined the old and fairly rotten political and medical administration, removed the restriction on admission of townspeople, formalised full access of Queen's College medical students and professors for teaching and was renamed the Galway Hospital.

LOCATION 15

ST. BRIDGET’S (St. BRIGID'S) CHAPEL AND LEPER-HOSPITAL PROSPECT HILL GALWAY

Founded in 1542 by the Corporation.

The Hospital played a major role in containment in 1571 of one of the last outbreaks of English Sweating Sickness, (sudor Anglicus) a highly contagious and lethal (<24hrs) disease that mysteriously appeared in 1485 after the Battle of Bosworth and had sporadic Spring outbreaks between 1485 and 1550s. The "sickness" devastated Tudor England until it then mysteriously disappeared again. Sudor Anglicus has been postulated in recent years to be possibly caused a rodent borne hantavirus with a very aggressive cardiopulmonary and high fever presentation.

St. Bridget’s Hospital was destroyed by Red Hugh O’Donnell’s soldiers in their attack on Galway in 1597. Rebuilt by the Corporation in 1614 it remained operational until 1652. It then fell into disuse and was occupied by squatters in 1688.

James Hardiman states that,

“The Hospital of St Bridget, in the east suburbs, was founded for the poor of the town, and each burgess was obliged, in his turn, to send a maid servant to collect alms every Sabbath day for its support.”

LOCATIONS 16 (& 27)

WIDOWS AND ORPHANS ASYLUM (CATHOLIC) 1824 -1870

THE MAGDALEN ASYLUM AND LAUNDRY 1870 -1984

The original Magdalene Asylum was established off Lombard Street in 1822 by a Ms Lynch and a lay Association of Mary Magdalene. In 1840 the Sisters of Mercy had come to Galway and in 1851 took charge of the Lombard Street Magdalene Asylum after Ms. Lynch had died. By this stage they had also been invited to take over the nursing care in the Workhouse Union Hospital.

The Widows and Orphans Asylum on Forster St. was first established in 1824 by a Rev Mark Finn, the Catholic Parish Priest of St. Nicholas Parish. The building subsequently came to be owned by the wealthy merchant Sebastian Nolan, and in 1870 he bequeathed it to the Sisters of Mercy. They subsequently moved the Magdalene Asylum and Laundry from Lombard St. to Forster St.

Nolan had made his money importing Peruvian guano fertiliser, and he was the founder of the original Galway Golf Club on Gentian Hill, on a course designed by Col Jourdain of the Connaught Rangers. A lifelong bachelor, it is said that the love of his life rejected him and became a sister of Mercy. In his will of 1907 (he died playing golf with local parish priest) he also left his home Seamount Villa and vegetables from his garden to the Sisters of Mercy. He left the today’s equivalent of €5.2 million to the Archbishop of Tuam. Seamount Villa later became a maternity nursing home until the lease ran out in 1952.

The Magdalene Laundries were not happy places. Indeed where illicit pregnancies were concerned they became the site of incarceration of repeat “offenders” as is evident from the provisions of the Local Government (Temporary provisions) Act, 1923:

Unmarried Mothers.

4. Unmarried Mothers are divided into two classes:—

(a) First offenders, to be dealt with in the same institution as children.

(b) Old offenders to be sent to Magdalen Asylum.

Unmarried Mothers who come within Class (b) shall be offered an opportunity of relief and retrievement in the Magdalen Asylum, Galway, upon such terms and conditions as may be agreed on between the Executive Committee and the Sisters in Charge of the Magdalen Asylum. If necessary the Committee may make arrangements with other Institutions.

Persons in Class (b) who refuse to enter such Institutions as may be selected shall not be allowed, under any circumstances to become chargeable to the public rates.

The societal attitude pertaining in the nascent Irish state in the 1920s in particular to containment of unmarried mothers and the subsequent management of both their live and dead babies has left a legacy which is not yet fully resolved.

In May 1926 the Committee submitted a recommendation to the Board of Health that it ‘…arrange for the establishment of a Maternity ward in the County Home for unmarried mothers (the Bon Secours run home in Tuam), as the admission of this class of patients to the Maternity Department of the Central Hospital tends to prevent respectable patients from seeking admission thereto’ (GC6/5, 12 May 1926, p2 my underlining).

In 1927 the Committee passed the following resolution, ‘That considering the prevalence of sexual immorality, as evidenced by the number of illegitimate births at the Maternity Hospital in Galway, this Committee deplore the departure from the old Gaelic traditions of purity, caused, in our opinion by the lessening of parental control, and the lack of proper supervision on the occasion of dances and other entertainments of a similar nature, and we therefore most respectfully suggest to the Hierarchy of this County, to appeal to the people, through the Clergy, for a return to the old Gaelic customs, under which such scandals were practically unknown’ (GC6/6, 15 June 1927, pp5-6).

LOCATION 17

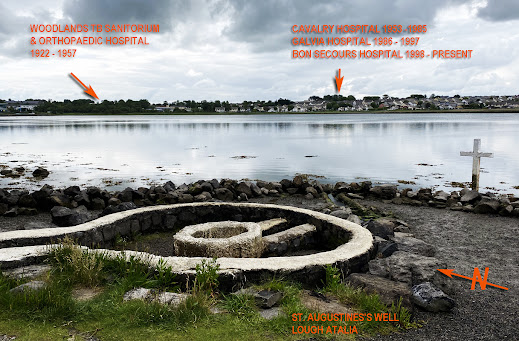

WOODLANDS TB SANITORIUM 1924 -1954

WOODLANDS ORTHOPAEDIC HOSPITAL 1954 -1962

In the early 1920s both medical (respiratory) and surgical Tuberculosis patients were overwhelming the capacity of the Central Hospital to manage them. In 1924 Renmore House at the northern tip of Lough Atalia inlet, on 17 acres was bought and converted to a Sanatorium and renamed Woodlands. In the years that followed a 10 bedded wooden chalet and two 40 bed pavilions were added because of the demand. In 1952 the respiratory TB patients were transferred to the new Merlin Park campus on the East side of Galway and the Sanatorium became a TB orthopaedic Hospital until it also transferred to Merlin Park in 1957. The site was taken over by the Brothers of Charity for their service commitment to children with intellectual disabilities and their families.

St. AUGUSTINE'S WELL

Tim Robinson, the die-hard Yorkshireman who became the greatest champion of the language of the Connemara lands ape wrote that as he became more aware of the cylindrical foreshore "holy wells", percolating up by tradition and usage throughout Connemara, he thought of them in existentialist terms as "motes of almost tangible meaning in the endlessness of the incomprehensible" and as an "inexhaustible reservoir of the possibilities of life."

As you walk northwards towards Woodlands on the west perimeter tidal shoreline of Lough Atalia there is St. Augustine's Holy Well and from a medical perspective its waters has long been associated with the traditional treatment of "Eye & Ear Ailments".

LOCATION 18

CALVARY HOSPITAL 1953 -1985

CALVARY MATERNITY HOSPITAL (PRIVATE) 1953 – 1975

GALVIA HOSPITAL 1986 -1999

BON SECOURS HOSPITAL 1999 –

The "Blue Nuns" or Sisters of the Little Company ofMary, were a vocational order dedicated to the care of the sick and dying. Founded in 1877 they first came to Ireland in 1888. They established a 70 bed hospital in 1953 and withdrew from its management and control due to diminishing vocations in 1984.

LOCATION 19

RENMORE BARRACKS MILITARY HOSPITAL 1880 – 1922

Decision to close Castle Barracks and Military Hospital in the town in late 1840s. New Barracks and Hospital designed by Captain Marcus Dill, Royal Engineers in 1855 but not built and occupied until 1880. Dill had died in 1867.

The Arts and Crafts design of building and the hospital ward layout influenced by the Florence Nightingale contribution to the Royal Commission in 1859 advocating a switch from the long wall bed system to the better ventilated and easier nursed hospital Pavillion system and ward lay out ( introduced into UK via France by the surgeon Robertson in the Manchester Lying-In hospital and George Goodwin editor of the Builder) where the ward was separated by a lobby from lavatory and scullery provisions and had a good ventilation and heating system. British Military hospital reform with the active encouragement and participation of Nightingale had been driven by Douglas Galton and Dr John Sutherland of the Army Sanitary Commission from 1861.

The Renmore Barracks St. Patrick’s Church across the road from Military Hospital was designed by a Sgt Major J.D. Passmore, RE and commissioned and paid for by Lt. Col Francis Hercy. It was completed in 1884.

LOCATION 20

THE CHOLERA ISOLATION HOSPITAL 1895 -1907

GALWAY PORT SANITARY INTERCEPTING HOSPITAL 1907 – 1948

BRITISH ARMY ISOLATION HOSPITAL Dec 1920 -March 1921; Jan 1922 -March 1922

The physical building at Rinville Point no longer exists. The building was burnt down in a fire in 1966 and in 1996 the remaining masonry and footprint of the hospital was eradicated when reclaiming and expanding the land around Rinville Point for the new Galway Harbour Docks Development.

The Hospital was first established in 1895 following the Cholera Hospitals (Ireland) Act 1893. By 1907 a fire destroyed the older Cholera Isolation Hospital building and the same year a new isolation hospital known as the Port Sanitary Intercepting Hospital was built on the same site at a cost of £630-00. It was never a very busy hospital as the great waves of cholera that had first hit in 1832 and persisted throughout the Great Famine years (particularly during 1848-49) had receded somewhat. In addition the hospital had come under the control of the Harbour authorities rather than District or County management.

One occupation of the hospital was to reach the level of UK parliamentary debate however in 1911 when 4 patients from a Norwegian ship with “beri-beri” were transferred there from the central Fever Hospital. One of these individuals was very belligerent and an attendant (much to the annoyance and cost of the Harbour Board) had to be hired to “mind” him. Three nurses and one attending medical officer were employed.

It became a military hospital in Dec 1920, on and off over 6 months. One of the last people to die in the isolation hospital was while it was under control of British military. A Michael Mullins, a former Galway footballer was transferred there with a fever from the “hell hole” internment centre in the Galway Town Hall and died from pneumonia on 3 Jan 1921.

In 1930 the Port sanitation officer reported that he had destroyed a “suspect” parrot under the mandate of the Importation of Parrots Act 1930. Disused by 1946, it burnt out in a fire in 1966 and in 1994 was razed to the ground as part of the harbour development plan.

There was also a Port Disinfection Station in the Commercial Dock.

LOCATION 21

POSSIBLE SITE OF KNIGHTS HOSPITALLER (TEMPLAR) CONVENT/HOSPICE 1230s - 1312

Hardiman in his history of Galway, and based on his interpretation of an oval area of ground on the 1651 map, writes in relation to the Catholic Military Order the Knight Templars (Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon), that,

“This famous Order had a convent here beyond the East Gate, but it was supressed in 1312, and its possessions granted by Edward II to Hospitalliers of St. John of Jerusalem. The circular foundation of this ancient building may be seen on the old map [1651 Pictorial Map] of the town at the S.W. corner of the Green.”

The Order in France had earlier been suppressed by Philip IV on Friday 13th Oct, 1307. The arrest warrant for the leaders of the order stated,

The arrest warrant started with the words: "Dieu n'est pas content, nous avons des ennemis de la foi dans le Royaume" ("God is not pleased. We have enemies of the faith in the kingdom")

The Knights Templar were a Military Order that developed a Hospitallier and Banking function as part of their expansion. The Knights of St John of Jerusalem were a Hospitallier Order (taking over the pre-Crusade hospital run by Amalfi merchants in Jerusalem that developed into the 1,000 bed St John's Hospital) that subsequently also evolved into a military Order.

First established using voluntary subscriptions in Galway 1822, moved to junction of Abbeygate St and Bowling Green in 1837 and then to Flood St in 1850, and to Workhouse Grounds in 1865.

Taken over by Galway Poor Law Guardians 1851 following Dispensary Act of that year.

Dispensary moved to Shantalla clinic in 1955.

Dispensary system ceased in 1972.

In 1848 the City Dispensary at Sally Long's recorded 2,376 attendances (black ticket) ,8,467 dispensions of medicines, 25 midwifery cases and 315 home visits (red ticket)

LOCATION 26

PROTESTANT WIDOWS & ORPHANS ASYLUM ON BOWLING GREEN AND LOMBARD STREET BARRACKS

Lombard Street is named after the Bankers from Lombardy whose fortunes intertwined with Galway's. In 1274CE a Thomas deLince was appointed provost or portreve of Galway and in 1280 he married Bridget Marshall, the grand-daughter of John Marshal, Marshal of Ireland. This branch of the Marshal family descended from the illegitimate son of John Marshal, the brother of William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke and Earl Marshal of Ireland. The senior Marshal line died out with no male heirs and in 1207 the hereditary Marshal of Ireland title was conferred by King John on the "junior" or illegitimate line.

Three years after Thomas deLince became provost, in 1277, either a brother or cousin of Thomas, a William deLench (deLince/Lynch) was appointed as the collector of customs duties for Galway, primarily acting as a Crown agent for the Ricciardi bankers of Lombardy, to whom Edward I of England was in hock. William deLench had to hand over these tolls to the Ricciardis in Dublin.

The arrangement between Edward I and the Ricciardi was to last until 1294 but is remembered in name of Lombard Street. Perhaps, even after the arrangement with the English crown ended in 1294, Lombard bankers remained in situ profiting from the wool trade and being in place to help fund the impressive Galway continental mercantile development in 14th, 15th and 16th centuries.

(see: http://deworde.blogspot.com/2016/10/rihla-journey-61-hall-of-red-earl.html)

What is now the flat space of the Lombard/Market Street Car park was originally the site of the Athy Town Castle and garden. After the Cromwellian surrender in 1652 and subsequent expulsion of the merchant families the Governor of the town was based in the tall town house. It became known as Rutledges tower. In 1717 it became the third of Galway's military barracks to be established and remained operational until 1822 when the Patrician Brothers National School was erected on the site.

At one point during the height of the typhus epidemic of 1822 it was converted into a temporary convalescent hospital of 100 beds.

The Wall to the right in the picture above where construction is taking place was the property of the Ffrench family and at the back wall was the Protestant Widows & Orphans Asylum. The Protestant Widows & Orphans asylum, a much smaller institution than the equivalent Catholic W&A on Prospect Hill was founded in 1820. It is uncertain when it closed.

As an aside, to illustrate the impact of disease and institution on literary matters I turn to the story of Nora Barnacle from the Bow (Saunders Lane) off Lombard Street.

NORA BARNACLE was born in the maternity section of Galway Workhouse Infirmary in 1884. She moved with her mother to live with her Uncle on Bowling Green in 1898.

Nora's first love (at 12) was a Michael Feeney from West William St who died at 19 years of age in 1898 of typhoid and pneumonia in the Workhouse Infirmary after a direct admission made possible by a change in legislation in 1892.

Her second love was a Michael Bodkin, from one of the "Tribes" families of Galway, who died in Galway Hospital formerly the County Infirmary on Prospect Hill from TB, also aged 19 in 1900. The change in law governing admission in 1892 allowed patients from the town to be admitted.

Nora's third love was William Mulveys, a Protestant, whom she began dating in 1902 when she was 18. When her uncle found out he beat her with a thorn stick forcing her to leave the home and run away to Dublin.

Nora met James Joyce on 10th June 1904 and had her first date with him a week later, on the 16th June 1904. It was this date that Joyce was subsequently going to use to set the events of one day in Ulysses.

Both Feeney and Mulvey were buried in Rahoon cemetery. Joyce was jealous of Nora's continuing affection for her dead "loves" and at one point set out for Oughterard to find their graves. Nora had not bothered to dissuade him with the information that they were buried much closer in Rahoon. In Joyce's famous short story "The Dead" Feeney and Bodkin are amalgamated into the "ghost" character Michael Furey.

LOCATION 27

LOCATION 28

SHAMBLES BARRACKS

In language terms Shamble, the etymologists point out, derives its ultimate origin from the Proto-Indo-European word skabh, meaning to prop up or support. From here transhumance in place and function generated the Latin scamnum, a stool or bench and in the diminutive form scamellum, a low bench. From Latin to the Proto-German scamel, the Anlo-Saxons brought sceamol with their axes to England and by the 14th century schamell and its ‘New English’ derivative shamble specifically meant a table or shelf from which meat was sold. By the 15th century Shambles as a descriptive plural noun began to refer to a defined area of the town or city where animals were butchered and sold.

The Shambles or Lower Citadel Barracks was first built in 1709 on the site of the Lower or West Citadel that had been built in 1652. The barracks was soon unfit for purpose and a new barracks was built in 1769 to hold 10 companies. In 1836 it had 15 officers, 326 NCOs and privates and 6 horses. It had only a small convalescent infirmary as most serious cases were transferred to the Castle Barracks Hospital. Directly across Bridge Street (down the small lane seen in bottom right hand corner of map above) was the horse market where horses for the cavalry regiments were bought.

The Shamble Barracks closed around 1890, was sold in 1909 and demolished in 1927.

LOCATION 29

THE LEPER HOSPITAL, CLADDAGH 1235-1451; 1488 - 1651

A Church dedicated to the Virgin Mary along with a Leprosy hospital building was established on Fairhill, Claddagh in 1235 by Canons of the Praemonstratensian Order from their base in Tuam. The land was donated by the O'Halloran family in whose tuatha or clan territory Galway established.

Research for early medieval England by Knowles and Hadcock suggests that about 1,103 hospital-type institutions existed. Of these 67% were "almshouses", 31% were leper hospitals, 12% were hospitium for poor travellers and pilgrims, and 10% were dedicated hospitalium for the poor. There were also infirmarias within monastic complexes for care of the monastic brethern.

The Praemonstratensians (known as Norbetine or White Canons) who established the Leper Hospital in the Claddagh were known as Canons Regular of the Order of St Augustine, as they adhered to the Rules of St Augustine for monastic life, and whose rules for the caring of the sick were less rigid and less exclusive than those who followed the Benedictine Creed.

Following the establishment of his monastery of Montecassino in 530, after destroying the Temple of Athena that stood there, the Rules of St. Benedict of Nursia governed the management of most hospital facilities attached to monastic establishments. This was reinforced by the edicts of Charlemagne in the 800s and monk-physicians delivered the majority of Christian associated care.

In the mid-12th century however the Gregorian reforms of the Lateran Councils began. In Canon 17 of the First Lateran Council of 1123 monks were banned from visiting the sick and what care continued emphasised the spiritual rather than bodily "diseases". Further restictions were to follow, such banning monks from training as paid physicians (1139) and practising surgery (1215), and this separation of monastic life from secular health caring was to be further reinforced in the late 12th century as a consequence of the Cistercian Order's re-emphasis of strict monastic community observance of the ascetic aspect of Benedictine rules. As a consequence "Benedictine" monks withdrew from delivering 'hands-on" care to the unclean public and monastic care declined.

Until the increasing availability of secular trained physicians in mid-13th century as a consequence of the Benedictine restrictions some of the Orders who then took over the care of, or established, institutions for the sick and dying and delivered that care abiding by the healthcare guidance formulated in the less strict monastic Rule of St Augustine such as the Premonstratensians and later the Dominicans. These were generally known as Canons Regular. Any monastic associated healthcare until suppression of the monasteries by Henry VIII was generally under the Rule of St Augustine.

The Dominican Order were granted the Premonstratensian Chapel of St Mary in the Claddagh in 1488 and established their Church of St Mary's on the Hill, after a dispute in 1495 with the Franciscans, in 1508. It became known as Abbey West by 1530. The Dominicans continued the operation of the "Leper" Hospital on the site from 1488 -1651 when the whole complex was torn down so that it could not act as a site for a cannon battery when the Town was besieged in the Cromwellian wars. The Dominican Chapel and Friary but not the Leper Hospital was rebuilt in 1669.

LOCATION 30

On 15th march 1922 in one of the last reprisals of the War of Independence Sgts John Gilmartin of Oughterard and Sgt Tobias Gibbons of Westport of the RIC were shot dead while patients in St Brides. This was 8 months after the truce, 3 weeks after the British Army handed over Renmore Barracks and 1 week after their remaining RIC colleagues had departed Galway and Tuam. On the same night a Patrick Cassidy, a Congested Districts Board’s official from Mayo was shot dead in a ward in the Central Hospital, where was recuperating from an earlier assassination attempt in Mayo. A National Army Military Tribunal of Inquiry was conducted 2 days after the shooting and a finding of unlawful death by unknown agents.

Hospital. was founded by Dr William Sandys and operated as a nursing home, cottage and surgical hospital and maternity hospital from 1916 – 1964. Surgeon Michael O’Malley and anesthesist Dr Joseph Waters. Conor O’Malley later joined acting as Eye and ENT surgeon as well as radiologist.

LOCATION 31

IRISH CHURCH MISSIONS ORPHANAGE

The 1800 Acts of Union also united the Established English and Irish Anglican Churches and as a consequence the newly energised and emboldened congregations in the 1820s, particularly in England, determined to utilise access to education to proselytise amongst Roman Catholics for conversion to Protestantism in Ireland on a missionary basis. They were later during the depths of the 1840s famine years to barter access to education and Protestantism as a means of access to food. These missionaries became known collectively as the “Soupers”.

By the 1840s educational missionaries proselytising on island included amongst others the Irish Society for Promoting the Education of the Native Irish through the Medium of their Own Language. The Irish Society, as it came to be known was founded in 1818 by Henry Monck Mason and others from within the ranks of the Association for Discountenancing Vice [founded in 1792, incorporated in 1801, erased from legislative memory by accident in the Statute Law Revision Act 2007 and reinstated to legal identity by the Statute Law Revision Act 2016] and often referred to as the Ragged Schools).

There was also the Erasmus Smith Elementary or Latin Schools (from 1809 onwards it had about 107 schools in addition to the 4 late 18th century grammar schools); the Incorporated Society for Promoting English Protestant Schools in Ireland (Charter 1753); the original “Irish Society” i.e. The Society of the Governor and Assistants in London of the New Plantation in Ulster (founded in 1613) with 8 boarding schools and 10 day schools mainly in northern Ireland; the Wesleyan Methodists (48 schools); the Presbyterian Connacht Scriptural and Industrial Mission; the Edinburgh Irish Mission; the Religious Tract and Book; the Irish Evangelical Society; and the Home Mission.

Into the maelstrom of misery and mortality that were the 1840s in Ireland, where failure of the potato harvest and absentee landlords had throttled the life and soul out-of an entire generation of Irish people, bestrode Alexander Robert Charles Dallas and his “cowboys” or agents of the Irish Church Missions to the Roman Catholics, determined to harvest souls for Protestantism in the midst of a failed potato harvest, and concentrating on the wasteland that was Connemara where people had suffered most.

On the 29th March 1849, the Rev. Dallas established the Irish Church Missions to the Roman Catholics with the determination to establish “Stations” – schools, churches and meeting-houses – throughout the country but in Connemara in particular.

In a letter on 27th July 1850 he wrote,

“I am led in a way I cannot refuse to undertake the practical working of a Society which aims at nothing less than the Protestantizing of Ireland…”

This determination to Protestantise was to become his paramount inspiration. A formal working “evangelical” coalition between the Irish Society and the Irish Church Missions came to an end in 1856 and the Irish Church Missions went their own way. In his remaining 20 years the Rev Alexander Dallas was directly responsible for the foundation of 21 churches, 49 schoolhouses, 12 parsonages and 4 orphanages in his work as Secretary for the Irish Church Missions.

The Orphanage attached to the Irish Church Mission School was established in 1862 and took in transferred children from the previous orphanage on Merchant's Road. The school in in 1868 had 29 boys and 36 girls. The Orphanage was known as the Sherwood Fields Orphanage or in local use "The Nest." The Orphanage and its Protestant-based missionary "souperism" closed in 1906. The building became a recreation centre for the British troops stationed in Galway and in 1933 Scoil Fhursa National School opened on the site.

For more information in regard to the Rev Dallas and the Irish Church Missions see:

http://deworde.blogspot.com/2021/01/rihla-69-castlekirk-caislean-na-circe.html

LOCATION 32

PUBLIC LYING-IN OR MATERNITY HOSPITAL 1826 -1842

A public Lying-In Maternity Hospital was proposed in 1824 and completed with a small garden in 1826. It remained open until t5he opening of the Maternity Section of the Union Workhouse Infirmary in 1842. The building was knocked down and replaced in 1990.

LOCATION 33

PROTESTANT ASYLUM (GRACE HOME) 1840s -

LOCATION 34

CHARTER SCHOOL AND FOUNDLING HOSPITAL 1755-1798

TEMPORARY FEVER HOSPITAL 1817 - 1818

The original building at the top of Mill Street had been founded as a Charter School and Foundling Hospital in 1755. The school closed in 1798 when during the Rebellion of that year it was taken over as an Auxiliary Artillery Barracks. The Barracks closed in 1814 and in 1817 it became a Temporary Fever Hospital. It was a ruin by 1818 and in 1819 the Presentation Nun's rebuilt on the site, establishing their School, Chapel and Convent.

LOCATION 35, 36, 37

MODEL SCHOOL 1852 - 1926

GALWAY DISPENSARY 1865 - 1923

The Galway District Dispensary whose previous homes had been at St Augustine St (1820s), Abbeygate (1830s), Flood St. (1850s) moved to a purpose built building on Newcastle Rd., adjacent to Union Workhouse in 1865. Incorporated into "new" Maternity Hospital in 1923 and moved into temporary buildings nearby. In 1955 the new Shantalla City Dispensary was established to rear of site of former Model School.

CENTRAL MATERNITY HOSPITAL 1923 -42

(ENT Department 1942 -1955)

LOCATION 38

RADIATION ONCOLOGY CENTRE

(To open Autumn 2022)

LOCATION 39

FEVER HOSPITAL 1909

Built on "Nightingale" Principles on stilts ensuring good air circulation.

Influenza “Spanish Flu” epidemic of Autumn 1918- Summer 1919 at its peak 10 patients a week dying in fever hospital.

LOCATION 40

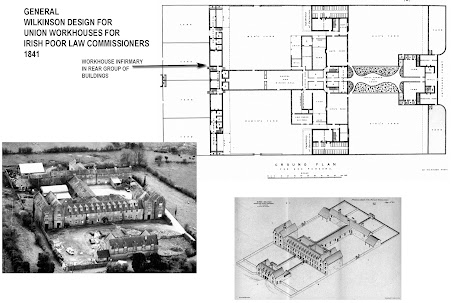

GALWAY UNION WORKHOUSE INFIRMARY (GALWAY UNION HOSPITAL 1842)

The Irish Poor Law Relief Act of 1838 was the first, albeit much criticised, universal attempt to tackle the health consequences of poverty in Ireland. 10 poor law unions were established in Galway county by 1849. In just 5 years between 1839 - 1843, under the guidance and energy of Poor Law Commissioner George Nicholls and architect George Wilkinson, 112 very substantial workhouses, including Galway, were built and made operational. On the 2nd March 1842 Galway's workhouse opened. The Workhouse was initially designed to accommodate 800 but later this increased to 1,000.

The famine and its ravished really impacted and during the peak years 1846 -1848 auxiliary workhouses were established in Dangan (where 1000 children were housed and which closed in 1853), Merchant's Road (1,000), Barna, St Helen's Street, and Barna in addition to temporary "fever" sheds in the grounds.

Two years later, on the night of 1851 census, when the peak impact of famine had passed there were still 2,099 people in the Galway Workhouse and 1,919 in auxillary workhouses (mainly Dangan), accounting for almost 6.5% of entire population of 61,500 in Galway Union. On the same census night the Galway Workhouse Infirmary held 320 patients.

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1862 allowed direct admission to the Workhouses Infirmary without the requirement that his/her family had also to be admitted to the Workhouse as destitute. The Infirmary then began the de facto public medical hospital for the city.

GALWAY CENTRAL HOSPITAL 1922 - 1956

GALWAY REGIONAL HOSPITAL 1957 - 1991

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE HOSPITAL GALWAY 1989 - present

The Workhouses closed Aug 1921, and Galway Workhouse was occupied by the British Army for a period. Thereafter the new Galway Hospitals and Dispensaries committee took over the running of the Hospital and it was decided to establish the Galway Central Hospital by phasing out the County Infirmary on Prospect Hill, closing the Workhouse Infirmary and then amalgamating fully in the main Workhouse buildings on the Newcastle Rd. site.

In 1957 the buildings that had formed the Old Workhouse (1841 -1921) and then the Central Hospital were demolished after the new 594 bed Regional Hospital complex was almost complete.

CENTRAL AND REGIONAL HOSPITAL MATERNITY

This opened in 1924 with 18 beds when the City Dispensary building was converted.

During the war years there was increasing discussion about building a new Regional Hospital. However as a consequence of increased number of cases of deaths from puerperal sepsis a specifically comissioned maternity building was begun in 1941 and completed in 1942. Further modifications occurred in 1983.

The old Dispensary became the ENT Department until demolished with the building of new Regional Hospital 1957

BEGINNING AND END OF WALK

For anybody who is interested I usually conduct this walk on the last Sunday of most months, from August to May. There is no cost involved and if you come and want to make a contribution then the Irish Red Cross or Cope Galway would be delighted to receive them. The walk lasts 3.5 - 4 hrs with a stop for coffee. If you are interested contact me at wynkindeworde@gmail.com.

References and Further Reading:

Binchy D A. Sick-Maintenance in Irish Law. Ériu. 1938; 12: 78 -134

Cousins M. The Irish parliament and relief of the poor: the 1772 legislation establishing houses of industry. 18th Cent Ireland 2013; 28: 95-115

Cook G C. Henry Curry FRIBA (1820 -1900) : leading Victorian hospital architect, and early exponent of the "pavilion principle". Postgrad Med J. 2002: 78: 352-359

Corless C, Linehan N. Belonging — A Memoir of Place, Beginnings, and one Woman's Search for Truth, and Justice for the Tuam Babies. 2021 Hachette Boorks Ireleand

Curtin G. Female Prisoners in Galway GAOL in 19th Century. J. Galway. Arch. Hist. Soc. 2002;54:175-182

Executive Summary of Final Report of Commission of Investigation into Mother And Baby Homes. 2021 Dept Children etc. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/22c0e-executive-summary-of-the-final-report-of-the-commission-of-investigation-into-mother-and-baby-homes/

Glatter K A, Finkleman P. History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19. American J Med. 2021;134: 176 -181

Grace P. Patronage and health care in eighteenth-century Irish county infirmaries. Irish Hist. Studies. 2017;41 (159); 1-21

Roopam K G, Ratan L G. Ancient History of Hospitals. Int. J. Research and Review 2020; 7(12): 1-9

Hardiman J. The History of the Town and County of the Town of Galway. Folds & Sons (Dublin) 1820. Clachan Publishing Edition (Reprint) (Ballycastle) 2020.

Horden P. The Earliest Hospitals in Byzantium, Western Europe and Islam. J. Interdisciplin. Hist. 2005; xxxv (3): 361-389

Kelleher J V. Irish History and Mythology in James Joyce's 'The Dead' The Review of Politics 1965; 27 (3): 414 -433

Litton Falkiner C. The Knights Hospitallers in Galway. J Gal Arch Hist Soc 1906; 4: 213-218

Luddy M. Women and the Contagious Diseases Acts 1864 -1886. History Ireland 1993; 1(1):32 -34

McCabe C. Begging, Charity and Religion in Pre-Famine Ireland. 2022 Liverpool University Press.

McDonald L. Florence Nightingale’s Influence on Hospital Design, Hospitalisation, Hospital Diseases and Hospital Architects. Health Envir. Res. Des. Journal 2020;13(3):30-35

Mitchel J. Queen’s College, Galway 1845 -1858. From site to Structure. J. Galway Arch. Hist. Soc. 1998; 50: 49-89

Murray J P. 1992 Galway: A Medico Social History (Kenny’s, Galway)

Prunty J, Walsh P. 2016 Irish Historic Town Atlas No.28 Galway/Gaillimh (RIA, Dublin)

Prentice M B, Richardson L. Plague. Lancet 2007; 369: 1196 -1207

Robinson T. Connemara — A Little Gaelic Kingdom 2011 Penguin Ireland

Sterns I. Care of sick brothers by the crusader orders in the Holy Land. Bull Hist Med 1983; 57 (1): 43-69

Watkins C. Sick-Maintenance in Indo-European. Ériu 1976;27:21-25