Tuesday, August 16, 2022

BOG WALK BEARNA 15th August 2022: A PURPLE HAZE

Thursday, August 11, 2022

RIHLA (Journey 75): THERMOPYLAE, GREECE – SACRED LANDSCAPES AND SACRIFICE – THE ÓCHI, SISU, AND SAMUD OF LACONICS AND LARRIKINS

Rihla (The Journey) – was the short title of a 14th Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar Ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada, who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling and somehow the title of Ibn Jazayy's Rihla of Ibn Battuta’s travels captures the ethos of many of the city and country journeys I have been lucky to take in past years.

SACRED LANDSCAPES AND SACRIFICE

“Irrespective of our creed or politics, irrespective of what culture or subculture may have coloured our individual sensibilities, our imaginations assent to the stimulus of names, our sense of place is enhanced, our sense of ourselves as inhabitants not just of a geographical country but of a country of the mind is cemented.”

Seamus Heaney

‘The Sense of Place’ (1977)

Preoccupations

This Rihla is about a journey into and through a geographical “sacred landscape”; the sacred landscape that is Thermopylae, Greece. As Heaney has alluded to his 1977 prose piece The Sense of Place "sacred landscapes" exist not as a consequence of a “culture or subculture” or of a “creed or politics” but because of the landscape itself. A European landscape whose true identity may first have established in the mind about 10,000 years ago, when, as the ice caps receded, points of reference evolved from the permanent enclosures for domesticated goats or pastures for domesticated wheat becomes “sacred” as it evolves into a “country of the mind”. That concept of geographical sacredness, of legacy, becomes something that must be protected, must be preserved at all costs.

The foundation for any geographical landscape to become truly sacred, I believe, is that it has been or will have to be solemnised – in the past or in the future – by the self-sacrifice of individuals; individuals who had or will have a choice to abandon their fixed points of reference and instead have died or will die for a “country of the mind” in order to protect their families, their community and their landscape.

The need for self-sacrifice needs some explanation. Sacred landscapes are distinct from sacred spaces or spaces of cultural heritage, although they can co-exist. Sacred spaces are where a community through usage and/or communal sacrifice or ritual has created an ethno-religious sanctuary, such as Olympia or Delphi, or the “sacred” constructs of isolation from the community and self-denial such as the monasteries of Meteora and Mount Athos, which I would visit later.

I made the pilgrimage, no that word denies my argument, I made a journey to Thermopylae to both see and understand the actual geography of “self-sacrifice” and to my surprise I found that the sacredness of Thermopylae is concelebrated by at least 4 solemn memorials to the “glorious dead”, heroes who had died in its marshes and defiles across 2,500 years – in 480 BCE, 1821 CE and 1941CE to highlight a few – resisting oppressors, protecting their friends, and defending the notion of Greece, a “country of the mind”.

SACRED WORDS

Thermopylae, Greece is the place of the “Hot Gates”. The thermo or “Hot” part of the word’s construction is due to the presence of hot sulphur springs at the location and the pylae or “Gates” part derives from the fact that there were three places in Thermopylae where the surrounding mountains jutted outwards in spurs terminating close to the coastline leaving just a small gap or “gate” for passage. Where Thermopylae was concerned the actions of selfless sacrifice were preceded by a tenacious resistance – from the Latin resistere, to “hold back” – for a greater ideal, it was about saying about saying óchi, “no, never” to protect that sacred landscape.

In modern Greek usage óchi (óχι) is a noun meaning “no”, but with an emphasis attached. It is derived in turn from Byzantine or Koine Greek ókhi (ŏχι), which in turn derives from the ancient Epic or Homeric Ionic Greek negative òvkí (no, never), whose alphabet and dialect had become dominant by the time of Herodotus’ histories of the Greek-Persian Wars. It is óchi but also sisu or samud that link the Thermopylae memorials.

Sisu is a Finnish word, describing a deeply valued national and individual characteristic of stoic and resolute resistance, of bravery, of independence, of extraordinary tenacity, of endurance in the face of overwhelming odds, where success is unlikely, and where martyrdom is a likely outcome. The word is derived from sisus, a Finnish word for the interior (of a body cavity) or the intestine and thus similar although not so grimly adhered to as ‘guts’ in the English language. Sisu’s adoption as an internationally understood description of a Finnish national characteristic began with the no-quarter resistance offered up to the Second World War November 1939 invasion by the Russians and which continued into the Cold War that followed.

Samud is an Arabic word, very similar in meaning to Sisu. Symbolised by the olive tree groves, and the volunteer Union of Palestinian Medical Relief committees established in the camps in the 1980s, the word means “steadfast perseverance”, and “staying put despite continuous assault” and has been adopted as a Palestinian cultural value, a national characteristic that epitomises a resistance to an Israeli ignorance of international law – and a selective loss of their own Jewish memory of ghettos – and the purloining of their land and liberties.

As an aside óchi, sisu and samud are words that at equally could be applied to the present-day fatalistic but determined Ukrainian resistance to yet another Russian invasion. The greatest example – at least most public – of this tenacity, perhaps, was the response of a Ukrainian Border Guardsman, on the small bare rock that is Snake Island in the Black Sea, when the Russian Warship Moscova (subsequently sunk by land-based Neptune missiles after a diversionary preliminary radar jamming drone assault on the ship) demanded the garrison of 13 men on the island surrender. The response of one guardsman holding his finger up and replying “Russian warship, go fuck yourself” became the world recognised anthem of Ukrainian resistance to the eponymous ambitions of Vladimir Putin. As a consequence Snake Island has become a Ukrainian “sacred landscape”.

On the morning of the day I visited Thermopylae the UN had reported an estimated total of 4,677 civilians killed since 24 February, including 321 children, in Putin’s “special military operation” in Ukraine. The names grated: Xerxes is Old Iranian for “ruling over men” and Vladimir is a name, which means “world ruler” in Old Church Slavonic. As part of background research for a thesis a number of years ago, in trying to get a better understanding of what drives humans to commit torture, and the gradual development of an International legal and Convention consensus to create a jus cogens outlawing its application, I studied Plato’s, Al-Farabi’s, and Marcus Aurelius’ notions of “philosopher kings”. The ideal and aspiration of exemplar “ruling” might have been, if it had been applied universally over the centuries, a possible brake to the use of torture. Unfortunately that brake, even where an agreed Convention in International law has been agreed, is so fragile even in the most democratic and most accountable of systems. At the upper echelons of avarice, the departure from prohibitive norms of the despots and the truly deranged permits them to play a board game of convenient or contrived umbrage, of “ruling” acquisition, of destruction, of a deliberate ignorance of sacred landscapes, of a wanton lust to exercise power as a paranoid justification for their belief systems. In addition the lack of control induced by a paranoia and enabled by a command-structure acquiescence to the “ruling” delusions results in unbelievable cruelty, torture, and rape being perpetrated by individuals on individual victims allowing a wilful dehumanization of men, women and children and indeed all that we are. These actions, unfortunately, are a recurrent fault line in our human behaviour and the counterbalance – sisu, samud and óchi – resistance and individual sacrifice, comes at enormous cost.

At a societal level we have tried repeatedly to come to terms with the atrocities of power such as Nazi Germany, the Allied use of hydrogen bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Stalinist Holodomor Ukrainian famine, Khmer Rouge Cambodia, Apartheid South Africa, the Hutu macheting of Tutsi Rwanda, Putin’s Russian “cleansing” operations in Chechnya and Ukraine, to name but a few in living memory. In trying to turn away from the “futility of war and the waste of mass death” and yet remembering the “glorious dead” we have increasingly tried to replace punitive justice (both extra-judicial and mandated) with the application of restorative justice and truth commission pathways to help better understand what drives us both to destroy and to fight back with equal intensity. These are lessons learnt almost, by definition, too late for the communities directly affected.

MIRABELLE

All these thoughts and more occupied my mind that morning. When driving on a long journey, by way of distraction when you cannot tune the car radio properly, or smoke the pipe you had given up about seven years previously, thoughts are random and triggered by departures and destinations. Thoughts of tenacity, and character, and increasingly fatalism dominated. Not good company when driving. I needed coffee… and diesel. Having left Athens at daybreak and taken the multiple tolled E75 highway that takes you through an ancient and sacred landscape that the Spartans would have recognized as Attica, Boetica, Locris, Phocis and Malis I turned off at the small coastal resort of Kamena Vourla to have breakfast and refill the car’s tank.

The town of Kamena Vourla, which is about 167 km from Athens, is a town in the territory that would have been known as Opuntian Locris. The town itself does not have a Homeric or epic history, it did not exist, or at least if it existed it did not register. The main Locrian port was at Kynos/Cynus – modern Livanates 15 km to the south-east – which was the home port for most of the ships that Ajax the Lesser used for transporting the Locrian contingent to Troy. It struck me however that the narrow 200m strip of land on which the main street restaurants, church and fun-fair of Kamena Vourla are situated, between the waters of the Malian Gulf and the escarpment of the Knimis mountains, is most like what I imagine the narrow strip of land at Thermopylae, further up the road, would have been like in 480 BCE, before the coastline of the Malian Gulf silted up and receded over time.

Kamena Vourla is now a slightly distressed town. It primarily established as a resort in the 1930s in the main due to its association with the thermal springs outside the town, which became famed for their therapeutic properties. Unfortunately that “therapeutic” effect was associated with waters that are radioactive with high concentrations of Radon, the breakdown derivative of Uranium. Radon is now understood to be the second biggest causation of lung cancer after smoking. For that reason most of the thermal springs and many of the 1930s hotels and facilities that developed along this coastline, including those serving the sulpher springs at the “hot gates” of nearby Thermopylae have been generally abandoned for their medicinal value although radon sampling in Thermopylae spring’s groundwater is being investigated as a predictor of seismic activity.

In exploring the town, away from the main street, the sweet cherry-red-coloured fruiting Mirabelle trees or Prunus domestica syriaca found growing wildly in abandoned plots 100m from the Malian shore seem like embers of a past glory. So much so that on my return to Galway I sourced and planted two of the trees (the yellow-fruiting de Nancyvariety) in my front garden. You get an overwhelming sense, as you take the old National Route 1 Athinon-Thessalonikis exit towards Thermopylae from the roundabout at the north end of the town, that Kamena Vourla is still trying hard to find its way into the future.

LACONIC MEMORIES

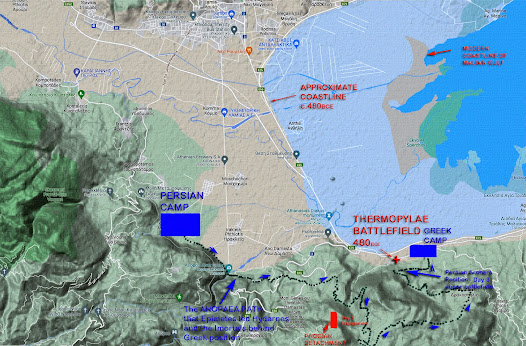

The National Route 1 runs mostly alongside the E75 for the remainder of its 25 km until they fuse at the Brállos/Bralos Pass junction with the E65. Indeed the modern route of the E75 Crete – Sweden motorway, as it winds its way around the western and north-western shores of the Malian Gulf, almost marks out exactly the coastline of 480 BCE when the Spartans under Leonidas and the other Greek forces established their redoubt behind the rebuilt Phocian defensive wall at Thermopylae.

The military action at Thermopylae, at the head of the Malian Gulf, was always intended by Themistocles, the Athenian general, as a combined land and maritime exercise to thwart the Persian advance in 480BCE by the Allied Greeks. On the maritime front the Persians were engaged by the Greek fleet at Artemisium on the north-east tip of Euboea, where the narrow strait into the Malian Gulf, that would bring the Persians behind the Greek forces, was guarded. The Persians had lost about a third of their fleet of 1200 ships to a storm off Magnesia and then because of the Greek naval deployment blocking the access from the east Xerxes dispatched another 200 ships to circumnavigate Euboea to enter the Malian Gulf from the south to attack the Allied Greeks from behind. These ships were also lost to another storm leaving about 600 Persian ships to engage the much smaller Allied Greek Navy. Following news that the Spartans had been beaten – there was a galley standing off shore of the much closer coastline of then to relay the information – the Greek naval forces, which were heavily outnumbered – they lost 100 of their fleet of 271 ships, – withdrew from Artemisium to Salamis where they regrouped and where they would inflict a decisive defeat on the Persian fleet later in the year.

Today, there are two memorial heroa or monuments to the “glorious dead” on the site. The larger memorial is to Leonidas and the Spartans and is a 2 meter bronze representation of a defiant Spartan warrior, by the sculptor Vasos Falireas, standing above a wall where two reclining statutes represent the land of the Spartans in the form of Mt Taigetos, the mythical mountain that looks down on Laconia and the river Evrotas which flows through it, either side of a metope depicting battle scenes. It was erected in 1955 and paid for by American Greeks. On the marble plinth beneath the statute are inscribed Leonidas’ reply to the Persian Ambassador for the Greeks to lay down their arms: ΜΟΛN ΛΑΒΕ; “Come and get them”.

The plinth with the Simonides epigram to the Spartans

on Kolonos Hill looking at the Thermopylae battlefield

The Spartan warrior statute is orientated west looking towards the Hill of Kolonos (across the NI roadway) where the Spartans made their last stand and where there is a memorial plaque that has replaced the lost (stolen) stone lion that had the famous epigram by Simonides (d. 466 BCE): “O stranger tell the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) that we lie here, faithful to our laws.” When you stand on the summit of the Hill the Battlefield of Thermopylae reveals itself in front of you. The hot springs at the base of the hill to the left and beyond the Phocian Wall the narrow strip of land between the escarpment and the E75 roadway that in 480 BCE had been rendered even more impassable, more marshy by deliberate flooding with water from the hot springs by the Phocians with just a narrow central causeway left for passage. Still the battle only lasted three days and from a Persian perspective was a minor but irritating part of a combined land and naval action to descend into Attica. Indeed even after the battle the Persians main route of assault was not along the shoreline but over the escarpment via the Bralos Pass, and then down the Kitisos river valley. Before departing, however, and frustrated by the resistance shown at Thermopylae Xerxes had Leonidas’ body decapitated and crucified post-mortem and it was almost 40 years after his burial at Kolonos that his bones were disinterred and reburied in Sparta.

The second heroön, a little to the north-west of the Spartans, is more modest and is dedicated to the 700 or so Thespians, the only other Greek hoplites who remained to fight and die alongside the Spartans at Thermopylae. I found this particular heroön more moving in its ambition and simplicity. It has a bronze statute with a representation of a puffed chest, headless winged Eros, whom the Thespians venerated. The headless representation is to define the anonymity of the Thespians who sacrificed their lives. The two wings are interesting. One is open symbolizing victory and glory. The other is “broken” and represents the voluntary sacrifice of the hoplites. The city of Thespiae in Boetica was subsequently denounced to Xerxes by the Persian allies and Thesbian rivals Thebes and razed to the ground. The Thespian heroön was erected in 1997 by the Greek Government.

Both heroa are testimony to a heroic and fatalistic resistance, a sisu that perhaps remains a partially misunderstood national characteristic of the laconic Spartans, and certainly that of the Eros loving Thespians, but accepted for Finns and increasingly for Ukrainians in their opposition to an almost archaic Russian hegemony.

I SHALL DIE A GREEK

The third heroön to the glorious dead in the sacred landscape that is Thermopylae is that dedicated to a heroic martyr who died resisting oppression in April 1821, during the early months of the Greek War of Independence. Athanasios Diakos, a former Orthodox deacon, with 48 comrades faced down an Ottoman army at a nearby bridge ( about 2 km on the E65 from Thermopylae) over the Sperchios river at Alamana. Diakos chose to stay and fight against overwhelming odds while the remainder of the Greek troops retreated. Diakos was captured, refused an offer to convert to Islam, saying “I was born a Greek, I shall die a Greek.”

Diakos was executed on the 24th April 1821 by impalement, a barbarous and horrendously painful and protracted form of death, more often associated with another Vlad, described at the time as a “demented psychopath”, Vlad III Dracula, Voivode of Wallachia (d.1477). The Ottoman Turks of the Barbary Coast generally dropped their victims onto barbed curved hooks set into the castle or town walls. Depending on angle of drop of victim the hooks could penetrate any point of the body and the time taken to actual death would be determined by the point of penetration. A quick death would have come with a chest penetration. The term “getting someone off the hook” originated from the practice of mercy killing, usually with arrows or cross bow bolts, a dying person impaled on the hooks, out of sight of the executioners. In Diakos’ case it is likely a wooden frame was erected with an embedded hook and he would have been dropped, bound, from a height onto it.

Known as the “First Martyr” in Greece, the sisu of Athanasios Diakos has been commemorated by many statutes and streets throughout the country and he is considered a national hero.

LARRIKINS

“Today, being a larrikin has positive connotations and we think of it as the key to unlocking the Australian identity”

Publisher’s Note: 2012 Melissa Bellanta, Larrikins: A History

Probably the Thermopylae battle that is perhaps least remembered is that which took place over 3 days in April 1941 when Allied ANZAC forces attempted to hold up a rapid German advance, long enough to allow the Allied Expeditionary force to evacuate from Greece to Crete. The fourth memorial heroön in the Thermopylae landscape is to one facet of this rear-guard action and it is on the escarpment above and to the south of the Asopos River Gorge as it enters the Malian Plain at Thermopylae.

About 2km to the north west of the Thermopylae battlefield the National Route 1 joins the NR 3 at the Brállos/Bralos E75/E65 junction. Dropping under the motorway you ascend the EO Livadias Lamias highway as far as the Weather Station half-way up the pass. Here there is a small slip road to the right that lets you join the old Bralos-Lamia road that winds its way downwards to join the Malian Plain at the exit from the Trachinian Cliffs of the Asopos River. After a series of hairpin turns there is a clearing at the north side of the road that allows you to park easily. Getting out of the car you are able to look out over the flat Malian plain towards Lamia and the Sperchios river, the flat plain that all conquering and revenging armies had to cross. The air the day I was there was hot, dust laden and hazy and the landmarks such as the Malian Gulf coastline to the east were ill defined.

On a square plinth in the centre of the clearing was a memorial plaque to the dead and injured soldiers of the 2/2 Field (Artillery) Regiment of the Royal Australia Army from a rear-guard action that took place on the 21st and 22nd April 1941. The 2/2 Field Regiment was formed in Melbourne, Australia in 1939. Initially part of the support for 17th Brigade the regiment subsequently supported the ANZAC 19th Brigade at the defence of the Brallos Pass as part of a rear-guard action protecting the withdrawal of Allied troops of the short-lived Greek Expeditionary or “W” Force in the face of overwhelming German advances.

Originally Italy had been delegated to attack Greece as part of the Axis Balkan campaigns during WW II. On the 28th October 1940 the Greek prime minister, Ionnis Metaxis allegedly rejected the 3-hour ultimatum of Mussolini’s ambassador to surrender Greece to Italy with the laconic answer, “Óchi!” or “No”, an answer that is celebrated as a national holiday in Greece as “Óchi day” on the 28th October every year. In truth Metaxis’ answer was “Alors, c’est la guerre!” in the language of diplomacy. Metaxis, a former general, was a monarchist dictator who on gaining power had decommissioned all high-ranking and experienced officers with Republican sympathies from the Greek army. The ability to plan and supply an army in the field effectively was entirely missing. As a consequence when confronted by the German invasion in April 1941 – following the failure of the Italians to make any progress by January 1941 - the Greek army command capitulated with ease exposing the Expeditionary 62,000 troops of W force and forcing the decision to evacuate after only a month at most in Greece. Thanks to the rear-guard actions of British and ANZAC troops, whom the Observer newspaper on the 27th April 1941 described as “displaying almost reckless bravery against the Germans, and are sacrificing their lives to ensure the withdrawal of their comrades”, the majority of “W” force were evacuated to Crete.

As a characteristic of the Brállos/Thermopylae action the tenacity of the arch typical Australian larrikin came to the fore. Brigadier George Vasey, commander of 19th Brigade at Brállos, who were tasked with holding back the Germans crossing towards Thermopylae from Lamia on the morning of 23rd April, said with absolute larrakin defiance, “Here we bloody well are, and here we bloody well stay.”

Vasey’s 19th Brigade were part of the combined 62,000 strong British, Australian, New Zealand, Palestinian Pioneers and Cypriot Expeditionary Force that began arriving in Greece on the 2nd March 1941. Winston Churchill wanted a force to be placed in Greece to create a Balkan Front to thwart the Germans then massing in Romania and convinced the Greeks to allow their deployment. The Australian and New Zealand commanders were suspicious of Churchill’s grand strategic plans, given he was the First Lord of the Admiralty whose decision it was to land ANZACs on the killing-fields of Gallipoli in WWI. They took some persuading but in the end agreed to send their troops.

In response the Germans accelerated their plans and began their invasion of Greece at dawn on the 6th April 1941 via Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. In true blitzkrieg fashion combining air, mobile artillery and infantry they soon overran Northern Greece. It took them just 3 days to reach Thessaloniki and take 60,000 Greek soldiers captive.

It soon became apparent to Wilson, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, that they needed to evacuate from Greece and following an order to do so by General Wavell, the commander of British forces in the Middle East, Wilson began a retreat of his forces in a series of leapfrogging moves. On the 16th April in order for the majority of troops to reach the evacuation ships he ordered a rearguard “last stand” action to be established by the New Zealanders at Thermopylae and Australians at Brállos, the “gateways” to Athens. The Germans attacked these positions on the 24th April, meeting fierce and devastating resistance from the forward Australian artillery in particular. On the first day 15 Panzers were destroyed and the whole German advance halted.

The Australian 2/2 Field Artillery Regiment (2/2 FAR) were raised in Victoria in October 1939. They were assigned in support to the Australian 19th Brigade, which with the New Zealanders had established the Thermopylae line by the morning of the 19th April. The road from Lamia at that stage was backed up for 10 Km with retreating troops but already the attacks with Stukka dive-bombers had begun. On the 21st April the 2/2 FAR were part of the retreating column climbing up the Brállos Pass. They had seen action 6 days earlier defending the Pineios Gorge.

During the retreat the Australian Artillery commander Brigadier Herring ordered two of 2/2 FAR’s 25-pounder guns to be pulled out from the column and under the command of a Lieutenant Anderson, to establish a forward ( and very isolated) gun position on a ledge at a narrow bend in the road that would cover the crossing of the Sperkhios River below. They were ordered to delay the German advance as long as possible to allow the other members of the Australia 6th Division escape/retreat.

Lieutenant Anderson and his squad engaged the German advance continuously for about 8 hours on the 22nd April. One gun was disabled by 1pm in the day and later in the evening the German artillery pounded their position killing 6 men and wounding 3 others, one fatally. Anderson evacuated his remaining men to the other 2/2 positions further up the Brállos pass but after dark returned with a Gunner Brown – a tram conductor in civilian life – to remove the striker mechanism of the guns and recover the dead soldiers discs and pay books. Anderson was to receive the Military Cross for his bravery. The 2/2 Field Regiment were eventually evacuated by a temporary made and then destroyed track on the evening of the 24th April. On the same day at Thermopylae New Zealand gunners destroyed 15 German tanks and damaged many more. Later that evening they destroyed their guns and evacuated to the south.

EXITS

“We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.”

In Flanders Fields.

John McCrae 1872 -1918

Canadian Military Surgeon and Poet

Leaving the Australian monument you continue on the old Brállos/Lamia road as it winds its way down the escarpment. It is overgrown in places and the bitumen potholed. You cross the temporary bridge over Asopos River as it exits the Gorge onto the flat, hot Malian plain – the older one with its polyhedral stonework got partly washed away in a torrent – and at the junction you look right towards Thermopylae battlefield and ahead the straight road to Lamia that all invading armies took when proceeding south. Thermopylae is a sacred landscape defined by its geography; the rites of passage through the “3 gates” of that terrain a template for the rites of passage, of initiation in the ancient structural sanctuaries of human construct. As in Flanders the solemnisers of that landscape are not the priests but those few, “the Dead” who “Loved and were loved”, who were prepared to self-sacrifice to resist oppression.

There are words to describe the actions of the protectors, of the glorious dead, and occasional heroön to remember them by, but to truly understand you must take the road into their sacred landscapes.

REFERENCES:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Artemisium

https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Thermopylae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athanasios_Diakos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impalement

Bongers A, Torres JL. A bottleneck combat model: an application to the Battle of Thermopylae Oper Res 2021; 21: 2859 -2877

Kraft JC. Rapp R. et al. The Pass at Thermopylae, Greece. J. Field Archaeology. 1987; 14 (2): 181-198

Mackay P.A. Procopius’ De Aedificiis and the Topography of Thermopylae. Am J Archaeol. 1963; 67(3): 241 -255

Michenko O.V. Classification Scheme of Sacred Landscapes. E. J. Geograph 2018; 9(4): 62 -74

Rop J. The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae. Historia 2019; 68(4): 413-435

Zarikas V, Anagnostou K.E. et al. Seismic activity and geochemical monitoring of thermal waters in Thermopylae. J. Applied Sci 2016; 16 (3): 113-123

Second World War Official Histories. Volume II – Greece, Crete, Syria (1st Ed.). 1953; Chapter 6: 131 – 159

Smith A D. The ‘Sacred’ Dimension of Nationalism. J. Int Studies 2000;29(3):791-814