Rihla (The Journey) – was the short title of a 14th Century (1355) book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling and somehow the title of ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos of many of the city journeys I have undertaken on foot in past years.

This rihla is about Dublin, Ireland

Perambulations would be another way of describing those journeys: wanderings of the spirit along the orbit of a city’s apogee and the personal sense of the impact of magical journeys on foot through palaces of hubris, places of worship, souks, streets and passageways is often difficult to explain to someone else. Literature has tried, even before the specific genre of travel literature developed, and has always incorporated in some way or other a perambulation or rihla of the heart and place. James Joyce, for example, was to ‘freeze-frame’ a city perspective on a single day in time by utilizing the wanderings of Rev John Conmee from the north to the south of Dublin in Ulysses.

Every city has had a moment in time: Athens, Rome, Carthage, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Isfahan, Granada and Cordoba, Istanbul in the 16th Century, London and Paris of the 17th and 18th, Barcelona in the 20th, Dubai in the 21st. Dublin of the early 19th Century is a case in point: an Iveagh tower.

A few years ago I spent an academic year travelling by early train every Friday morning from Galway to Dublin in order to get to afternoon lectures at the University College Dublin campus in Earlsfort Terrace where I was studying for a Higher Diploma in Forensic Medicine. Somehow that year the weather was invariably kind for walking and arriving about 10.45 I would always wander from Heuston Station to the jewel in Ireland’s crown that is the Chester Beatty Library, stop for lunch in the museum’s Silk Road Café and then travel onwards towards south-eastern corner of Stephens Green slightly varying my route each time to take in a different aspect.

With each of those journeys it was impossible not to experience the physical impact that the Guinness family had on the geography of Dublin. Past the site of the St James Gate Brewery that Arthur Guinness had obtained a 9,000 year lease on in 1759, up Watling St to the site of the original James Gate in the city walls, down Thomas St to Cornmarket, High Street and Christchurch. Across the road to Castle Street, turning left into Little Ship Street past the sentry box and into the precincts of Dublin Castle. A sharp turn right would then bring me to the Chester Beatty Library. A quick brouse of whatever exhibition was on, a lingering look at some of the rare manuscripts on display and then down the steel and glass staircase for coffee and food at the museum’s café.

After finishing lunch, usually with a sweet Lebanese pastry, I would then wander out again down Bride Street, past the Iveagh Baths and Iveagh Buildings, the affordable housing and facilities built by the Iveagh Trust, the successor of the Guinness Trust established in 1890 by the 1st Earl of Iveagh, Edward Cecil Guinness. Edward Cecil the great-grandson of Arthur, bought out his brother Arthur's, the 1st Lord Ardilaun’s, half-share in the brewing company in 1876 and was to float the company on the London Stock exchange in 1890. Lord Ardilaun’s Dublin Artizan's Dwellings Company of 1875 was to be the forerunner of Lord Iveagh's Guinness Trust and between them the towering red-bricked monuments to their sense of civic responsibility framed the landscape of my walks. Ardilaun also was to acquire and renovate St Stephen’s Green and donate it back as a gift to the people of Dublin in 1876.

James Joyce was to subsequently refer to the two brothers as Bungiveagh and Bungardilaun, after the ‘bungs’ or stoppers used to close the beer kegs, and as the ‘lords of the vat’. The majority of the building work paid for by the Guinness family took place in an area of Dublin known as the Liberties.

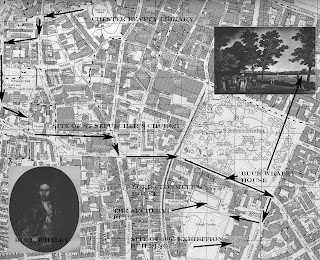

Speed's Map of Dublin and St Sepulchre

Note that Speed scaled the distances involved in 'Pases' for all good perambulators.

At the junction of Bride Street and Kevin Street there is a large Garda or police headquarters. The site was once the location of the Palace of St Sepulchre’s, the headquarters of the Manorial lands of St Sepulchre and the centre of the Liberties of the Archbishop of Dublin. The Liberties were originally lands outside the city walls which under Royal patents dating back to 1180 allowed the manor to have their own courts of justice where they were allowed to try all crimes except "forestalling, rape, treasure-trove and arson", free customs, freedom from certain taxes and services, have their own coroners, rights of salvage, maintain their own fairs and markets, regulate weights and measures, etc. Many of these priviledges were removed by 'An Act to abolish the Jurisdiction of the Court of the Liberties and Manor of Saint Sepulchre in and near Dublin, and for the future Regulation of certain Markets of the said Manor' on 21st July 1856.

The Manor of St Sepulchre’s and the Archbishop of Dublin’s lands extended as far as to where St Stephen’s Green and Earlsfort Terrace meet now and are linked by Kevin Street Upper and Lower, Cuffe Street and Stephen’s Green South (formally Leeson Street). The fields to the south of Stephen's Green – known as Leeson Fields in the 1750’s – were acquired from the Leeson family by John Scott, the 1st Earl of Clonmell and a Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench in Ireland. Scott was known as ‘Copperfaced Jack’ and lived at 17 Harcourt Street. He developed the thoroughfare now known as Earlsfort Terrace at the eastern end of the fields and laid out the remaining land in a rudimentary fashion as a pleasure garden. (I intend coming back to Copperfaced Jack again in another blog particularly with regard to his hanging sentence role in the famous Heiress Abduction Trials).

1st Earl of Clonmell

After his death in May 1763 his son renamed the fields the Coburg fields in honour of the Hanoverian Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales who had died in childbirth and who had married into the Saxe-Coburg-Saalfield dynasty (The direct ancestors of the current house of Windsor as after Charlotte's death her uncle Edward was quickly married off to her sister-in-law and that union produced Queen Victoria – who also married another Saxe-Coburg although a Gotha this time in Albert.)

The 1st Earl of Clonmell was a close friend of the famous Dublin bon-vivant and lynch-pin of the resurrected Hellfire Club Buck Whaley who lived nearby at No. 86 Stephen’s Green. In an irony of intent and behaviour the Whaley family house, built in 1765, subsequently became part of Newman College( along with No. 85 and a Victorian Hall), the foundling site of the Catholic University of Ireland (UCD)of 1854 and the later alma mater of James Joyce in 1902. As an aside, in my own case the graduation ceremony for The Forensic Diploma took place in the Whaley’s living room with its ornate carving of Orpheus. If only the walls could have spoken. Imagine James Joyce and Buck Whaley in conversation. Neither of them listening to the other or even interested but conducting a conversation nonetheless.

I’m getting to the end of this particular journey and my walk through the Iveagh bower. In a sense the journey although linear in direction was almost circlular in spirit as I had applied and was accepted to study Architecture in UCD at Earlsfort Terrace in 1974. I subsequently declined the offer in favour of Medicine in UCC and had no regrets but as I climbed the stairs to my lectures I would remember that the Architecture portfolio interview in 1974 had been conducted in the same room with its marvelous Richard King stained glass window.

The Earlsfort Terrace university building and the National Concert Hall attached are the structural remnants of the exhibition hall built for the Dublin Exhibition of 1865 on lands donated by Benjamin Guinness. Benjamin, the father of the 1st Earl of Iveagh, had bought the Coburg fields from Clonmell’s heirs in 1862 (they had been open to the public from 1812), and his house was at 80 Stephen's Green, which is now the Department of Foreign Affairs. He also had the part of the fields not used for building landscaped into a pleasure garden by the landscaper Ninian Niven. Within the design there is one of Dublin’s only dedicated and sunken Archery Butts (College Green in Trinity College was also originally an archery ground known as Hogge’s Butt), a faux waterfall, and pathways lined by armless statues left behind when the exhibition finished. Benjamin Guinness gained his Baronetcy for sponsoring the 1865 Exhibition in 1867 and when his son Edward Cecil became an Earl the gardens were formally renamed. They were donated to the state in 1939.

Note the statuary, many of which are still to be found stalking

the Iveagh Gardens nearby.

The 2008 statue of the singer Count John McCormack beside the Earlsfort Terrace Gate singing

to a headless nymph hanging about from the 1865 Exhibition.

The Iveagh Gardens, accessed through a small gate at the back of the Earlsfort building and from Clonmel Street (only one 'l' nowadays), are a real oasis in modern-day Dublin and during the mid-afternoon break in lectures I would wander and smoke my pipe and try to calculate the time on the sun-dial in the far south-western corner. Bishops, Lords, Libertines, Earls, and Counts have all contributed to its being.

The Iveagh Gardens: A true liberty within the Liberties, without.

.

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment