Rihla (The Journey) – was the short title of a 14th Century (1355 CE) book written in Fez by the Islamic legal scholar Ibn Jazayy al-Kalbi of Granada who recorded and then transcribed the dictated travelogue of the Tangerian, Ibn Battuta. The book’s full title was A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling and somehow the title of Ibn Jazayy's book captures the ethos of many of the city and country journeys I have been lucky to take in past years.

This rihla is about La Pared, Fuerteventura, Canary Islands.

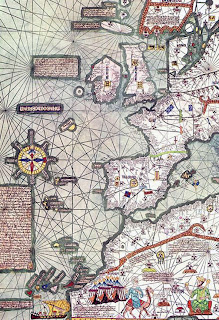

The Catalan Atlas of 1375

Canary Islands named bottom left.

In 1404 Gadifer de La Salle landed on the black, volcanic sand of Ajui on the western side of Fuerteventura with a mixed force of French and Castillian soldiers to continue the conquest of the Canary Islands that he and Jean de Béthencourt had begun in 1402 in Lanzarote. At the time of de La Salle’s landing de Béthancourt was in Spain having the title Lord of the Canary Islands bestowed upon him by Henry III of Castile and trying to raise more troops but later joined de La Salle in Fueteventura and founded the first settlement in a valley about 10 km inland, a town that still bears the senior adventure’s name, Betancuria.

Frontpiece from the Le Canarien,

a journal of the conquest of the Canaries,

showing de Béthancourt and de la Salle.

From Roman Times (and particularly as a consequence of Claudius Ptolemy’s 150 CE Geõgraphikê hyphêgêsis or Geography) the Canary Islands had been called collectively the Fortunate Isles but it was in the 1339 portalano of Angelino Dulcert (de Dalorto) that the island was named separately as Forte Ventura (Great Fortune).

When de La Salle and de Bethéncourt invaded in 1404 the island was known to the native aboriginal peoples as Erbania.

The native aboriginals, the Majos were primarily of Bronze Age Berber stock from the north-west corner of the adjacent African mainland, stranded by wind and time on the island, and who spoke a Lybico-Berber dialect. In that dialect ‘bani’ is a word for a low stone wall and Erbania as a name for the entire island derived its origin from a low stone wall built across the narrowest portion of the island to indicate the separate territories of the Kingdom of Jandia in the south from the Kingdom of Maxorata in the north.

Statues of Ayoze and Guize above the

town of Betancuria. Fuerteventura

In 1405 with the help of the mother-daughter local priestesses Tibabin and Tamonante de Béthancourt managed to get the two opposing Kings at the time, Ayoze of the Maxoratas and Guize of the Jandia to become baptised Christians, and surrender overlordship to the Norman in return for retaining landrights and exemption from tribute for nine years.

The native population (leaving aside those sold or taken into slavery) appeared to have been assimilated in the main with the invaders. (Of note de Bethancourt’s own nephew and heir as Lord of the Islands in Lanzarote, Marciot de Béthencourt married the daughter of the local Lanzarotian King but later became tyrannical and sold the islands to the Portugese in 1448).

Back to the Wall!

About 30 km south of Ajuy is another volcanic beach and port known as La Pared or The Wall in Spanish and it is from here that the ancient wall separating the Jandians from the Maxoratas originated. According to the guidebooks segments of the Wall still exist but when you ask about it nobody is quite sure where exactly.

And this is not surprising.

Dry stone-walls in Fuerteventura are generally made from volcanic pumice stone and whether the wall was erected yesterday or 2000 years ago in the absence of dating pottery or coinage or plastic they appear the same. The wall that separated north and south was not defensive like Hadrian’s Wall or the Great Wall of China but literally a line in the ground, a border to indicate organisation of a tribal society, a demarcation to reduce hostility. Sometime in the past, long before the European conquest, warring tribes had called time-out and decided on the Wall. It then became a symbol of everything in that society, it was not a mere pile of rocks: it was Erbania.

The headland at La Pared inlet, Fuerteventura.

I pondered on this notion of intentional isolation, while huddled in a typical Canarian beach stone-walled circular windbreak against the strong northerly wind that drove Atlantic waves crashing onto the La Pared shoreline, and thought of Pink Floyd’s Roger Water’s disaffection with a Montreal audience and the expressed desire to build a wall between him and the audience, and his feelings of abandonment and isolation. The expressed disaffection (and spittle) that was to result in The Wall concept album of 1979 and songs like Empty Spaces, Is There Anybody Out There? or Outside the Wall.

In my bunker of separation from the winds and sand I extracted from my knapsack the book I had brought for holiday reading: A History of the World in Twelve Maps by Jerry Brotton, a fantastic exploration of the importance in historical terms of 12 key developments in cartography. I had reached his 5th chapter entitled Discovery, which concerned the 1507 World Map of Martin Waldseemuller.

Besides its value as probably the first map to name the newly discovered (or re-discovered!) American continent it was more for his contextual analysis of the map’s publication as a verification of the 15th century Renaissance humanist developments. Brotton writes: What is found at the historical moment of the creation of any world map is not the inviolable identity of its origin but the dissension of disparate stories, competing maps, different traditions.

As I reared my head above the parapet of pumice, for some reason the backward message to Luka in Roger Waters’s Empty Spaces song from the Wall suddenly resurrected in my consciousness. Was the space beyond the wall truly empty, or do we as a society create spaces of imaginary ‘emptyness’ by erecting artificial barriers to desire, to discovery, to intercourse? Are we so afraid of the ‘dissension of different stories, competing maps, different traditions’ as to try and separate them in space. To cross from one space to another within society implies some form of consent. But from whom? Is it from within oneself or without from society in general?

Before leaving for Fuerteventura I had been examining, from a medical perspective, the true nature of consent and had just finished reading an article in the Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy: Special Issue on Justice, Legitimacy and Diversity on the tradition of “Consent” in society by Gerald Gaus, a philosopher from the University of Arizona.

In contrasting John Locke’s (1632-1704) rejection of a medieval supremacy rooted in God-granted rights and his liberal social contract declaration based on Natural Law that all people are intrinsically free and equal and that prospective political authority or the legitimacy of any state must be based on the individual consent of the governed with the Immanuel Kant's (1724-1804) perspective that because of an a priori Idea of Reason, and the absence of justice in Nature, a social contract is necessary to fully realise individual freedoms, rights and justice and the notion that individual consent to the legitimacy of that contract is subsumed to the notion of a primary duty to participate, Gaus concluded in Mevlana fashion that there is a role for both approaches. Consent is basically a form of reconciliation of the individual with society, and that different traditions have different strengths in achieving that reconciliation.

And this is what the Wall is, was: a reconciliation of that early Erbania society.

There and then I felt the need to see for myself as to whether there were any obvious remnants of the Wall at La Pared. Logic, reason even, told me the wall must have ended where the land cascaded into the sea and getting up from the shelter (of reason!) I walked to the far end of the beach and climbed up the spur of land that jutted out from the village towards the sea. Halfway up I was certain that I had found what appeared to be a faced wall, so obvious and so unmarked as to then immediately dismiss it as a volcanic rock formation. I am still not certain and will just have to leave my photographs of it as a question posed.

The 'WALL' at La Pared looking east.

The 'WALL' at La Pared looking south.

On returning to Ireland I turned to Google Earth to try and explore the terrain more closely. A definite linear feature appears to completely cross the isthmus on the first line of hills just on the northern edge of the sand plain. The pictures that follow show a portion of a wall traversing the north facing slopes just above a dry bed about 5 km east of La Pared, and crossing that river bed at one point. This continuity would not be characteristic of field enclosures where the rivers edge would provide definition. The rest is conjecture. Again it is for the reader to judge.

Regardless whether this is the Wall or not, its existence remembered in the name of Erbania, in that of La Pared, and by the Canarian peoples, was of far greater importance than its physical construct. The Wall was a product of individual and collective reason, and a reconciliation of the legitimacy of a societal contract.

No comments:

Post a Comment